Invasive Species

When I was getting my MFA in poetry ten years ago, I was told form was dead, or alive only for very conservative “neo-formalists,”—and I was sternly advised not to try it. I tried it anyway, and apparently so did others, because there are a lot of non neo-form types doing beautiful things with form. I was so knocked out by the first poem, a sonnet, in Terrance Hayes’ Wind in a Box I typed it up and put it in my pocket and read it for a week before I even got to the second poem. Something about his repetition of the sound of the dropped gut, the “uh” sound. “This blood,” he writes, “This blunder,” so there’s an internal rhyme all the way through, one note pounded and pounded, “This mud. // This shudder,” the sound tugging you down the page through rhyme and enjambment. Reminds me of leather boot laces threaded through the eyes and pulled tight. With give, there’s added strength, tightness. If this was the only good poem in the book I wouldn’t even care, it’s that great to read.

There’s something about a great formal poem as the opener of a book that has a special action, and this is why I thought of Hayes’ poem when I was reading “poem to be read from right to left” in Marwa Helal’s Invasive Species, written in a form of Helal’s own invention called “The Arabic.” This poem teaches us how to read it, and if you look to Helal’s “Notes” at the end of the book she teaches us how to write it, too. This is both an act of generosity and anger, which makes sense for someone who begins her book with this Chinua Achebe quote: “Let no one be fooled by the fact that we may write in English, for we intend to do unheard of things with it.” “poem to be read from right to left” explains how to read it so that its frustration can be heard:

of tired got i

number the counting

words english of

to takes it

in 1 capture

another

Helal writes, forcing discomfort. I was amazed at how difficult it was for me to fluidly read the poem from right to left. Just when I think I’ve got it, bam, there’s a stanza break and my eyes begin at the left again. Just when I think I’ve got it again, I realize I’ve begun to memorize it, and I’m not reading with my eyes. Helal writes in her notes that her aim is for the poem to “vehemently reject you if you try to read it left to right.” This rejection aims to “transfer the feeling of every time the poet has heard an English as Only Language Speaker” say something horribly condescending. Given this note, the poem creates a conflict I can’t seem to get out of: on one hand its frustration is well-founded and more than fair, but on the other hand, the form of the poem opens it up, allows it to be read so slowly that I find I actually read it, stay in it awhile. Reading this way is illuminating: the discomfort of ignorance, the flicker of sound as I learn an Arabic letter shaped like a hook or a slanted capital J sounds like the English word “lamb.”

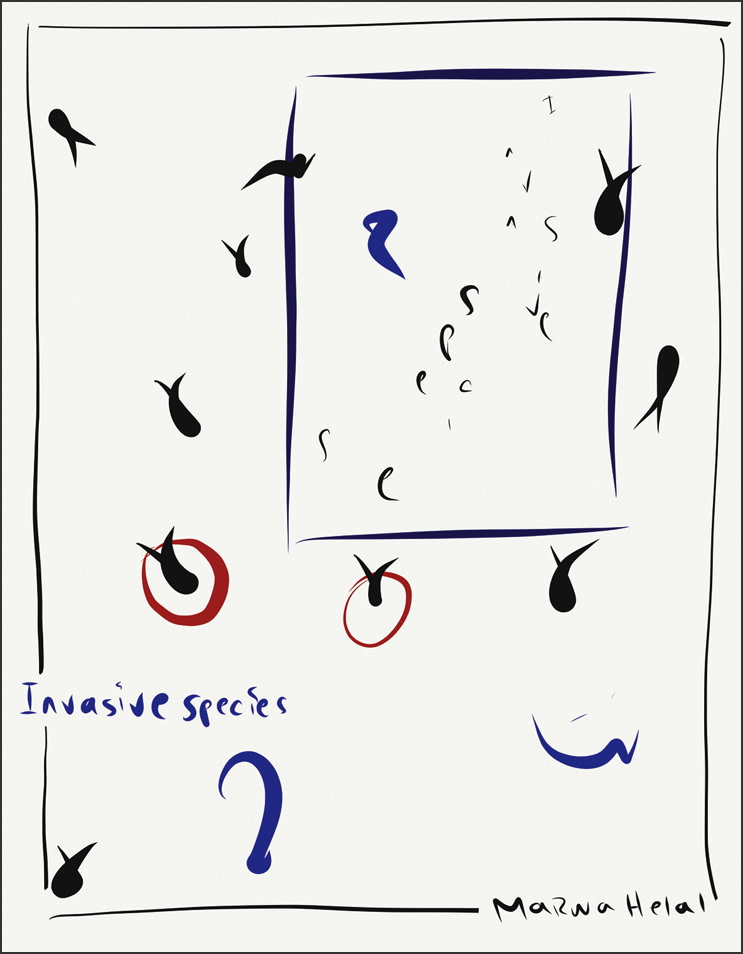

Helal worked as a journalist and trained as a nonfiction writer, and these poems, like Claudia Rankine’s, (who is clearly an influence) make me question the difference between poetry and reportage. This is a real project book, rather than the collections of shiny one-offs I’m used to seeing in first books, and it doesn’t have a ton of perfect little lyrics of the type I’d like to quote to hook you—it builds as it goes, and its perspective and emotion feels earned. In the end, it’s this poet’s faith in form that drives me through the book, from the square hole in the middle of “poem for brad who wants me to write about the pyramids” to the abecedarian poem-essay “Immigration as a Second Language” that makes up the long middle section of the book. “Poem for brad” who “is hot so the class / lets him get away/ with being dull” is both funny and mean, and as the title suggests, responds to a colleague in a workshop who “says

egypt is a wonderfully exciting place ([he is]) told by others) /

[he does] not like my scenes of policemen and sunflower seeds

/ says [he has] heard the pyramids are very interesting.”

I wish I’d had the guts to write this poem, only mine would be for Scott, and it would sound petty. Because it’s really, really hard to write from being mad about something like this, no matter how legitimate, without coming across as a jerk. This poem risks meanness, but that risk pays off, I think, because of how it merges poetry, journalism, and formal craft. This poem grounds itself by using brackets to show where Brad’s workshop notes have been emended, gaining my confidence in their accuracy, which leads to trust in the literal hole in the poem. The emptiness at its center looks like a window, a box, a frame, the empty base of the pyramid that poor Brad wanted, a place to mark ignorance, Tahrir Square. Reading the poem it seems to me nothing is missing, and yet, visually, something is. It bugs me, and I think that’s the point, “let every letter represent a human standing in protest,” this poem ends, and so the hole is bothersome, a place without letters.

This is an overtly political book, offering readers a highly interior view of the way immigration policies shape an individual life. “Immigration as a Second Language,” describes Helal’s return to Egypt at twenty-one, (her parents moved to the United States when she was two) and her years-long struggle to return. Complete with meticulous footnotes, a person unfamiliar with this Orwellian labyrinth can get a real education here in painful thinginess: white vans, what color a green card actually is and which versions are valid, tracking and grouping systems, the poet’s hatred of embassies. In recent years I have felt increasingly wary of poems that pop up in the midst of a political moment, seeming to have been born instantly as Athena burst from the head of Zeus. That was a one-time thing. It can’t always work that way. I question the role of poem as that kind of instant media, I measure the distance between William Carlos Williams’ assertion in “Asphodel, That Greeny Flower” (later taken up by Adrienne Rich) that

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there

and Rilke’s suggestion, in The Journal of My Other Self, that only at the very end of life might a poet have enough gravitas to “write ten good lines.” Only when memories have “turned to blood within us, to glance and gesture, nameless and no longer to be distinguished from ourselves—only then can it happen that in a most rare hour the first word of a poem arises.” Rilke was only twenty-eight when he wrote this, and in a self-effacing mood, and didn’t hold even himself to this standard. Between these two differing notions from an entirely different time, Helal’s poems seem to make space for themselves: “From-from?” a poem in this section asks with its title: “Where am I from-from? Where are you from-from?” In moments like “from-from,” which perfectly reflects a familiar and grotesque syntax, these poems don’t feel instant at all. Rather closer to Rilke’s “glance and gesture.” It’s important to separate, politically and artistically, the difference between something that feels instant because the artist (or consumer) has just been made aware of it, from something that is of crucial contemporary importance, made by someone who grapples with it every day. These may overlap, but their making is not the same.

In one of the finest poems I’ve seen written as the toilsome Oulipian “Beautiful Outlaw” or “Belle Absent,” a form in which each stanza must use every letter of the alphabet except the one corresponding to its title, (look it up, it’s a great one to try) Helal’s poem “the middle east is missing” engages in an act of multi-dimensional mapping:

…i want to walk/ return maps to managers

of mapmakers

i’d like to see god’s atlas compare it to ours trace a new equator

a river nile still running azure

azure

This poem comes early in the book, but engages many of its central questions and images:

before i left i wrote: where you from? where you from? where you

from?

There is so much work in sound here—the half rhymes of “managers,” “mapmakers,” “equator,” and “azure” suggest Helal’s conclusion that “we made a new map from breath.” In other words: words. Form and content themselves are in half rhyme. It’s as if the act of returning the maps to the ugly (sonically and otherwise) “managers” leads to the beauty of “azure.”