I Can't Talk About the Trees Without the Blood || dark // thing

Reviewed by: Jessica Smith

June 28, 2019

In 2018, the Equal Justice Initiative opened The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a.k.a. the “lynching memorial,” in Montgomery, Alabama. This memorial honors the “more than 4400 African American men, women, and children who were hanged, burned alive, shot, drowned, and beaten to death by white mobs between 1877 and 1950.” This complex interactive monument has multiple components. In its most photographed part, it features “over 800 corten steel monuments, one for each county in the United States where a racial terror lynching took place. … [But the] memorial is more than a static monument. In the six-acre park surrounding the memorial is a field of identical monuments, waiting to be claimed and installed in the counties they represent. Over time, the national memorial will serve as a report on which parts of the country have confronted the truth of this terror and which have not.”

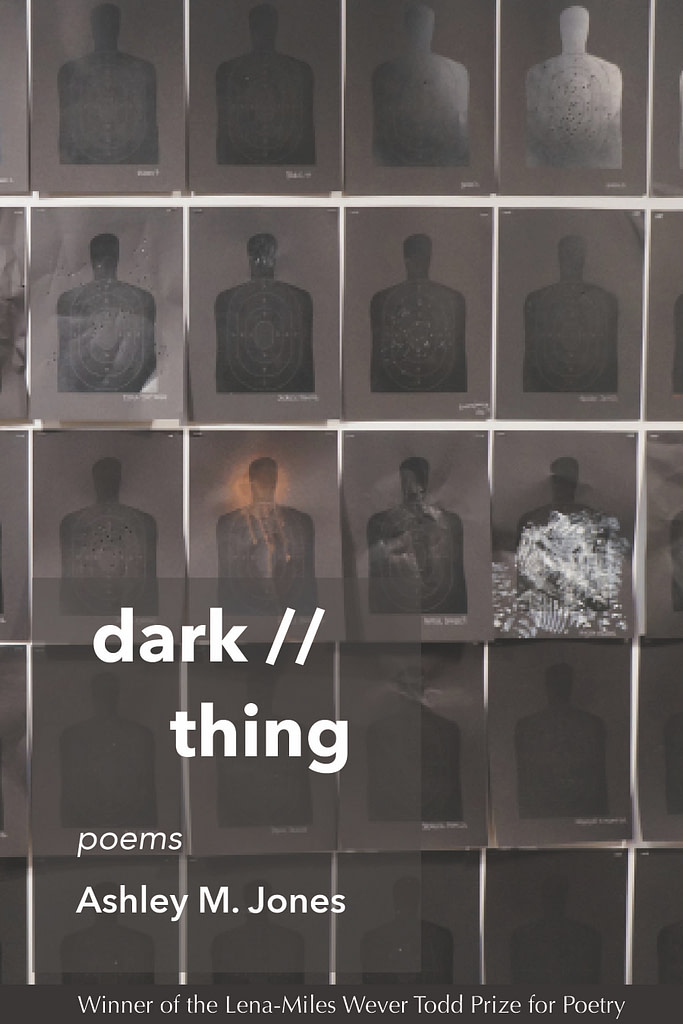

As we confront America’s history of racial violence and its present, ongoing violence, we are blessed with books like Terrance Hayes’s widely acclaimed American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassins (Penguin, 2018) that hold up mirrors to society so that we can educate ourselves and improve the world we live in. Two more important contributions to this conversation are Tiana Clark’s I Can’t Talk About the Trees without the Blood (U of Pittsburgh, 2018; the cover features art by Hayes) and Ashley M. Jones’s dark // thing (Pleiades, 2018). Like the 2018 lynching memorial, these books use multiple forms to communicate the legacy of violence against black bodies.  In American Sonnets, Terrance Hayes reclaims the classic European sonnet form to talk about the legacy of European colonialism and the slave trade in America, i.e., systemic racism and violence against black bodies, especially black male bodies. In contrast, Clark and Jones use various forms. Jones’s dark // thing could be used as a textbook in a creative writing class, as she pulls out all the stops to tell multiple stories with a playful sense of form. One thread in dark // thing is Harriet Tubman’s story, which is told through mathematical proofs (18), free verse (25), a “broken sonnet” (30), abecedarian (27), “recitation” (31), and free verse responses to quoted research. Like many of her poems about Tubman, “Avian Abecedarian” (27-28) begins with a long prose quote from research on Tubman’s life—in this case, from Sarah Hopkins Bradford’s Scenes from the Life of Harriet Tubman. Jones’s poem takes off after the description of Tubman evading her captors by creating a distraction with chickens at a market:

In American Sonnets, Terrance Hayes reclaims the classic European sonnet form to talk about the legacy of European colonialism and the slave trade in America, i.e., systemic racism and violence against black bodies, especially black male bodies. In contrast, Clark and Jones use various forms. Jones’s dark // thing could be used as a textbook in a creative writing class, as she pulls out all the stops to tell multiple stories with a playful sense of form. One thread in dark // thing is Harriet Tubman’s story, which is told through mathematical proofs (18), free verse (25), a “broken sonnet” (30), abecedarian (27), “recitation” (31), and free verse responses to quoted research. Like many of her poems about Tubman, “Avian Abecedarian” (27-28) begins with a long prose quote from research on Tubman’s life—in this case, from Sarah Hopkins Bradford’s Scenes from the Life of Harriet Tubman. Jones’s poem takes off after the description of Tubman evading her captors by creating a distraction with chickens at a market:

And what is a feather

but a song of praise? The wing, a

cacophonous hallelujah, adon’t

even try to hold me back, mister, these

feathers made by

God! (27)

Jones’s poem dramatizes the historical encounter, giving Tubman the bold voice and sense of urgent purpose that she must have had to be so brave. She uses the “abecedarian” form, where each line starts with the next letter of the alphabet. The abecedarian here conveys a sense of 19th century samplers and the power of literacy. Frederick Douglass famously wrote, “once you learn to read, you will be forever free,” but Jones takes a different tack in lines S through X:

…. Harriet, be a

salve to our sounds, quiet us when we want

to fly,

up and out of the

vice grip these men have made with nothing more than

words on paper—freedom or servitude marked with a hasty

X— (28)

Although many slaves were illiterate in English, there were other methods of devising freedom. White slave owners made and traded bills of sale, but slaves made maps, quilts, escape routes, bursting through the languages with other ways of communicating. Perhaps these alternative paths to freedom are echoed in Jones’s formal play: the systemic racism that underlies language and how we use it—even in experimental art forms like poetry—could be disrupted by new ways we use language.

A second thread in dark // thing that I find particularly haunting when listening to Jones’s live poetry readings is the subject of lynching. In dark // thing, lynching is told through forms ranging from charts and graphs (49) to free verse to ekphrasis. Jones’s research led her to the subgenre of lynching postcards, and she gives ekphrastic descriptions of these gruesome cards before writing responses to them. Lynching postcards were “banned from circulation” by the post office in 1908 (34). Prior to that, they featured pictures of lynchings and were mailed to black people as threats. In “Uncle Remus Syrup Commemorative Lynching Postcard #25,” Jones combines the racist dialect from Uncle Remus ads, “dis sho am good,” with descriptions of white people at a lynching party in a conspicuously breathless text block without stop punctuation:

Dis sho am good [his eyes, white gumballs] Dis sho am good Dis sho am [look how the tree holds him taut] Dis sho [and Betty Lou brought all that delicious fried chicken her gal made, so crunchy, so sweet we even ate the bones] Dis show [the perfect weather …. (34)

Jones paints a picture of how white people behaved at lynchings as if they were fun picnics. The poem reads like a social gossip column or the back of a postcard exchanged between friends, the gossip contained in brackets while the front of the postcard contains the Uncle Remus slogan, as though the poet were flipping the card back and forth between these realities to see the thaumatropic relation between them.

In her overture to I Can’t Talk about the Trees without the Blood, “Nashville,” Tiana Clark prefigures multiple themes she will explore, including similar themes as Jones:

… Southern Babel, smoking the hive of epithets hung fat

above bustling crowds like black-and-white lynching photographs,

mute faces, red finger pointing up at my dead, some smiling,some with hats and ties—all business, as one needlelike lady

is looking at the camera, as if looking through the camera, at me, … (xiv-xv)

As is clear from the title, Clark’s book discusses how to be alive in the present when surrounded by forests of generational and individual trauma. How to see the trees for these forests: “Yes, I’m always looking back // at my dead” (49). In “Soil Horizon,” she writes about a time when her mother-in-law asks to “take the family portrait / at Carnton Plantation” (13). “She said Can’t we // just let the past be the past?” “I said it was fine as long as we weren’t by the slave cabins, and she laughed // and I laughed, which is to say I wasn’t joking at all.” Clark can’t just let the past be the past:

How do we stand on the dead and smile? I carry so many black souls

in my skin, sometimes I swear it vibrates, like a tuning fork when struck. (13)

Clark seems to experience a kind of intergenerational post-traumatic stress disorder, feeling the painful anxiety and sensitivity of knowing that people who looked like her were enslaved and continue to be brutalized. How does one take portraits on the grounds of a former plantation? Recently, there’s been a rash of white people taking family portraits in cotton fields in Alabama, following the “mason jar and burlap” aesthetic. How do people manage to block cultural memory out of their minds while taking photographs for the future? Or do they? The title “Soil Horizon” reminds me of an “event horizon,” that boundary beyond which there is no escape. The soil of the plantation cannot escape the blood that was spilled there. The speaker cannot escape the weight of memory and history.

As Jones takes Harriet Tubman for her chosen ancestry, Clark appeals to Phillis Wheatley (16-23) or as Hayes epithets, “God forbid, Wheatley” (Sonnets, 5). In “Conversation with Phillis Wheatley #7” (18-20), the imagined ghost of Wheatley asks the speaker, “Have you ever been for sale?” and the speaker describes being sold at a debutante charity auction. As a Southerner who has attended such events as a guest without the appropriate heritage to appreciate them, I share Clark’s mortification even without sharing her skin tone:

Old Money looked me up and down and back again, placing

and tracing my origin. All evening, they kept asking me

who made my dress Who made your dress, dear?And to repeat my last name: Knight I said. Knight

as in black as the night sky above, everywhere stabbedby blinking stars. Meaning: I come from the back

of the store, disheveled sale racks, everything 70% off,marked down, price stricken through

with a giant red slash. (20)

Even after “freedom,” which Wheatley was eventually granted and Clark has, there are nets woven of class and race that are inescapable. African-American enslavement isn’t what it used to be, but the monied, landed gentry of America inherited the wealth created by the economics of slave labor and unblinkingly continue these odd cultural ceremonies celebrating whiteness, power, female virginity, and the marketing of bodies.

In both Clark’s and Jones’s books, there are line breaks over multiple lines, as is indicated in Jones’s title dark // thing by the double slash marks. In retyping excerpts from the poems above, I indicate multiple empty line breaks with that double slash, but it also represents the elision of a line that might not be empty. The presence of this double slash in Jones’s title and of white spaces in visually experimental poems in both books may indicate that even while the authors tell their stories, they hold space for all the ghosts whose voices remain silenced.

There are so many more topics to explore in these two volumes, such as the complexities of black hair, the tragic deaths of young black men, the toxic masculinity of grown black men, and the search for safety in havens like church, foodways, and grandmothers. Reading them alongside Hayes’s celebrated American Sonnets adds female voices to a conversation about how black people might survive—and rewrite—American history.