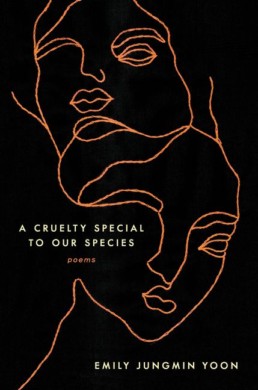

Emily Jungmin Yoon's A Cruelty Special to Our Species: Containing Anxious Ambiguity, with Peaches

I was beside myself, a ghost slightly to the side of my body. I remember the thin, harvest gold carpet. I remember the black tables and swivel desk chairs bolted to the floor. My friend Andrea’s wet red eyes. Eun-Gwi Chung’s firm voice reading her poetry. I was 21 the first time I learned about “comfort women.”

“Comfort women” is a euphemism used by the Japanese army for Korean sex slaves. The women were conscripted by the Japanese from areas they occupied, like Korea and China, as well as flat-out kidnapped. Wikipedia uses the term “prostitute,” but the more accurate term is “child sex slave” as the “women” were often underage girls, unpaid, held against their will, undernourished, gang raped, beaten, not given adequate medical treatment, fed arsenic for syphilis, forcibly sterilized, killed, buried alive, or left to die. Some survived and made their way back home to reclaim what they could of their lives. A Cruelty Special to Our Species reworks the testimony of these survivors in persona poems.

It is impossible to simply list the crimes against these women, and that’s where poetry steps in. In the first poem of Cruelty, one of a few prose poems titled “An Ordinary Misfortune,” a friend asks the speaker: of Japan and Korea: “Why don’t you guys just get along?” (3). The book might be read as one answer to this question, and other poetry books might help round out the picture (I’m thinking of Don Mee Choi’s Hardly War, which I reviewed for Jacket2 a few years ago). Korean resentment of Japan is not simple; Japan has committed atrocities against Korea for centuries. As other international disagreements are not wars with clear edges that can be cut out like benign cysts, Korea cannot necessarily be expected to “just get over it,” as women who are raped, individually, not as whole countries, cannot be expected to “move on” (3).

The first section of Cruelty, “The Charge,” sets up the “charge” against the Japanese army, but by extension it also accuses men on the street, the American media (“Hello Miss Pretty Bitch,” 7) and the American army during the Korean War (“An Ordinary Misfortune,” 6). The Japanese army might be technically responsible for the “comfort women” as a class during a particular time, in a particular place, and we will soon get to the particulars of those war crimes. But Yoon implies that the problems of the way men treat women are not limited to a particular time, place, or circumstance.

In the second section, “The Testimonies,” Yoon lays out the evidence, gathered and reworked from actual survivor testimonies (viii). The speakers of these poems are the “comfort women” themselves. One formal element that particularly struck me in these poems is the way Yoon breaks some lines:

Girls arrived got sick pregnant injected

with so many drugs nameless animals

exploded on top of us

The day of liberation Suddenly,

no sound of horses the last soldier

stood in the kitchen “Your country is liberated,

and my country is sitting on a fire.” (15)

The stilted breaks of “The day of liberation Suddenly, / no sound of horses the last soldier” where those caesuras might also be read vertically–– “The day of liberation / no sound of horses / stood in the kitchen // Suddenly, / the last soldier / “Your country is liberated”––reminds me of the feeling of traumatic dissociation. The lines jump from thought to thought and hold both at once, yet doesn’t hold anything clearly. Here’s a slightly different use of this ambiguity:

Kobayashi

took me

to a hut Every evening

soldiers (18)

In this passage, we can simply read left to right, top to bottom, as we usually do: “Kobayashi / took me / to a hut Every evening / soldiers.” But we can see more than one word at a time; we are not word processors with tiny screens. We can simultaneously apply every phrase on the left to the phrase on the right, gaining the horror of repetition: “Kobayashi / every evening / took me / every evening / to a hut / every evening / soldiers / every evening.” The way “Every evening” is placed on the right makes it radiate toward all the words on the left, reinforcing the long-term gang-rape the speaker experienced.

Although the poems in “Testimonies” largely read “as usual,” top to bottom, left to right, they contain these small moments where the eye can cover material differently. A final example:

I should forget and forgive but I cannot

When my head turns toward Japan I curse her

I want to find solace but I cannot

When I wake up every morning I cannot

Here, the lack of punctuation and the way that the right hand column is aligned invites us to read both ways: our usual left-right, top-bottom mode, and in two columns, “I should forget and forgive / When my head turns toward Japan / I want to find solace / When I wake up every morning” “but I cannot / I curse her / but I cannot / I cannot.” The second column feels like an internal echo, as when one has a thought and then immediately reacts to it, like an electric shock. Because we don’t really read just one word at a time, we can contain both these reading possibilities at once. Containing this anxious ambiguity reinforces, for the reader, the feeling of never being settled with what has happened.

The third section of the book, “The Confessions,” contains a web of material. In one strand, as she writes the book (38), the speaker’s/author’s experiences of learning in English in America (36), of being a contemporary Korean tourist in Japan (35), and of having non-white hair as a Korean child in America (39), convey a sense of otherness. The speaker feels alienated everywhere. Even the home she finds in her lover’s arms (38) is problematic, as her lover is white, which she fears her mother will dislike, and as she has nightmares when she sleeps with him. In another strand, the surviving comfort women have similar nightmares and describe feeling haunted, hating men (31), their legitimate sorrow feeling false or hollow due to the centuries of “countless foreign invasions” (32) and the resulting intergenerational trauma and cultural grief. A third strand addresses toxic masculinity: the peer pressure to use the comfort women, even if a soldier didn’t want to, in order to prove himself “a man” (42); the speaker’s shock when her Korean boyfriend signs up for compulsory military service and makes jokes with his American friends about “killing all the North / Koreans” (40). The flip side of this is that the men are, themselves, sometimes soft and comforting. The crook of the arm of the speaker’s white American boyfriend “has become [her] favorite room / for sleep” (38). In “My Grandmother Reminisces with Peaches” (41), we read a lovely poem where the male suitor, who becomes the grandfather, brings gifts to the grandmother:

He wasn’t a romantic, you know.

But he always left a basket of peaches

at my feet in the summer. (41)

His tender gesture shows that men can be kind. They can find “the one / unblemished peach” and their bodies can provide comfort and rest (“My cheek dreamt well on his heart”). Men are not only rapists, harassers, and warmongers, although they often choose to be in these positions or are forced into them. This section, and indeed the entirety of Cruelty, reminds me of Judith Hermann’s seminal book Trauma and Recovery, in which she writes:

Fifty years ago, Virginia Woolf wrote that “the public and private worlds are inseparably connected . . . the tyrannies and servilities of one are the tyrannies and servilities of the other.” It is now apparent also that the traumas of one are the traumas of the other. The hysteria of women and the combat neurosis of men are one. Recognizing the commonality of affliction may even make it possible at times to transcend the immense gulf that separates the public sphere of war and politics—the world of men—and the private sphere of domestic life—the world of women.

For the men depicted in “The Confessions” section of Cruelty, war and its concomitant crimes against civilians are part of a cultural imperative to prove one’s manhood by killing and raping people. But Yoon indicates that men are also capable of great affection and tenderness: it is not necessary that they become rapists and warriors. The present is haunted by the brutality of the past, but there are other possible futures.

“The After” is the final section of Cruelty, and although “The Confessions” would seem to set up a neat ending where men are redeemed, this last part of the book shows that everything just gets more complicated. In consensual relationships, women are manipulated into sex (48). Women abandon and abort unwanted children from these men (50, 51). The original comfort women, the impetus for the book, are paid reparations from the Japanese government and “this issue is resolved finally and irreversibly” in 2015 (53). The speaker struggles with the narrative and the act of writing poetry in the wake of continuing violence: “Silly girl. Silly, silly girl for thinking that writing line / after line of beastly beatitudes will help her. How silly, / how silly, silly, silly, silly.” (59). How does one end a book when there is no meaningful resolution to the problems the book addresses? Yoon’s solution is to raise the level of complication one more notch, by writing about whales in her final three poems. Like the women of wartime, these whales fall victim to man’s total lack of consideration for their lives, and like the long-silenced comfort women, Yoon’s anger rises to the surface:

…. Whales die in this year’s hot winter.

Your father has told you of the summer, the dank heat.

Your foster mother ran after you, you already asleep in your father’s arms,

wailing your name. You will not be called by that name the next day

and years will pass by. But when you’re ten, you will write about that story

and spell wail as the animal, whose breath is a distance, spouting steam,

the great animal that becomes crushed by air and sprayed with words

Man’s Fault. And yes, so perhaps the world will end in water, taking with it

all loving things. And yes, in grave. Only song, only buoyancy. You rise now

whispering, murollida, murrollida. Meaning, literally, to raise water,

but really meaning to bring water to a boil. (66-67)