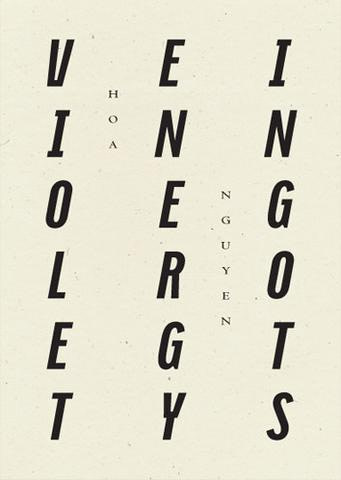

Violet Energy Ingots

Opening transcendent portals outside of culture and time through which the divine might speak, the oracle of antiquity was called upon for advice on urgent matters ranging from the public sphere of politics, war, crime, and duty to the private realm of personal concerns. Delivering messages while frequently in a trance, the oracle’s answers were often ambiguous; operating outside of rationality and valued for this very fact, the question and answer exchange thus embodied a unique and productive tension between the quotidian and the extra-ordinary.

Opening transcendent portals outside of culture and time through which the divine might speak, the oracle of antiquity was called upon for advice on urgent matters ranging from the public sphere of politics, war, crime, and duty to the private realm of personal concerns. Delivering messages while frequently in a trance, the oracle’s answers were often ambiguous; operating outside of rationality and valued for this very fact, the question and answer exchange thus embodied a unique and productive tension between the quotidian and the extra-ordinary.

Introducing Hoa Nguyen at a Poets House reading this June, Stephen Motika called her work “oracular,” a descriptor immediately resonant with Violet Energy Ingots, Nguyen’s latest book, for the way it addresses the urgency of the contemporary political and cultural moment through a range of registers—quotidian, fierce, enigmatic, imagistic, conversational—in a lyrical, fragmentary, and, at times, beyond-sense modality. The first page of the three-page poem “Autumn 2012 Poem” opens the book and provides a sense of the fluidities and tensions throughout:

Call capable

a lemony

light & fragile

Time like a ball and elastic

so I can stop burning the pots

wondering yes electric stove

She is her but I don’t re-

member remember

the ashes I obsess She said

I was obsessed with

(not wanting to work with

ashes)

Mandible dream

says the street

& ash work

Here the domestic kitchen setting and lemony scent combines with the darker, mysterious “ash work” and “Mandible dream” to create a larger existential setting where questions of memory, which are questions of history, play out. Nguyen’s pairing of the quotidian with mystery is particularly significant at a time when many poets have turned in the opposite direction, toward narrative and polemic as vehicles, with ethical-aesthetic questions oftentimes revolving around the authority of first-person identity and witness. While Nguyen’s poems are resolutely present to the current moment, they engage the world—its rifts and traumas, its incongruent beauty—with a somewhat different approach.

Much like the dynamic of exchange between seeker and oracle which sets into play the rational language of asking with the lyric language of oracular answer, for Nguyen the how of language is as important as its topics. This is not to say that the book doesn’t engage explicitly with both public and private events. To the contrary, there is a poem written on the anniversary of September 11th, a poem that marks the seventieth anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, moments addressing race (“I lied to the white observers / in the dream”), as well as a birthday poem, poems of dreams, of friends and family. These moments are never given as monumental, but are instead set within the quotidian: “Auto dish soap / 1/2 and 1/2 / Coffee beans”; “swimming pool tango and cold fruit salad”; “My job is to put red-hot candies/ into a pale-green bowl.”

Similarly, the fabric of Nguyen’s language registers the wear of historical trauma while never entirely being delimited by it. “Haunted Sonnet” provides an example of this:

Haunt lonely and find when you lose your shadow

secretive house centipede on the old window

You pronounce Erinyes as “Air-n-ease”

Alecto: the angry Megaera: the grudging

Tisiphone: the avenger (voice of revenge)

“Women guardians of the natural order”

Think of the morning dream with ghosts

Why draw the widow’s card and wear the gorgeous

Queen of Swords crown Your job is

to rescue the not-dead woman before she enters

the incinerating garbage chute wrangle silver

raccoon power Forever a fought doll

She said, “What do you know about Vietnam?”

Violet energy ingots Tenuous knowing moment

Although each of the sixty-one poems in Violet Energy Ingots is singular and builds in response to particular moments its own form, imagery, allusions, and tonal register, “Haunted Sonnet” contains elements that permeate the book. For instance, none of the poems have punctuation; rather, they rely on capital letters and white space caesurae to register stops and starts and shifts. Throughout, the tension between standard syntax underlying the lines on the one hand and the use of enjambment, fragmentation, and lack of punctuation on the other creates the effect of listening to a record as someone is picking up the needle and then putting it back down at slightly different places in the album or song. This creates a sensation of channeling—the poem letting through various frequencies of voice and experience. The technique also disrupts illusions of completion: any given utterance is a fragment of a larger, unknowable whole.

Another formal tension suggested throughout the book and seen in “Haunted Sonnet” involves Nguyen’s threading-through of her predominant organic form with a minor thread of constrained forms. Eighteen poems use the couplet as principle organization, and four poems, one of which re-writes Shakespeare’s 117, are fourteen-liners titled “sonnet.” There is a “ballad” and two of the book’s poems are derived from alphabetically arranged first lines from other poets (Jack Spicer and Tagore). While these constrained forms are never mechanically employed and are minor in comparison with the book’s organic techniques (e.g. lack of punctuation, white space caesurae, and variable line and stanza lengths) the inclusion of constrained forms suggests the inescapable pull of history and tradition’s patterns—even as the poet pushes away from convention.

“Haunted Sonnet,” which both is and is not a sonnet—and which is punctuated by absence and a vivid immediacy, employing swift shifts and fragmentation at the same time that it enjambs and floods—well-embodies the formal tension at work throughout Violet Energy Ingots. Carrying these signature formal techniques through the book affords the work continuity even as it ranges in tone, diction, and the visual pattern of the page. Indeed, these signature tensions are so deeply stitched into the manuscript that we might read the title itself as a description of them: Violet (a plant found both wild and cultivated, a color which might appear solid but is a wave of light); Energy (the kinetic body in motion, the potential body defining itself through the stresses created by the bodies around it); Ingots (both a mold in which metal is cast and a mass of cast metal—form is content and content is form).

Also carried throughout the book and evident in “Haunted Sonnet” are references to mythological figures: here, the Erinyes—the Furies: Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone. Notice the attention this poem gives to sound, showing readers how to pronounce Erinyes, which connects to a larger arc of the book that demonstrates listening to the past: “Autumn 2012 Poem” states: “abide the advice was// not ‘Fair better’/ but ‘Fail better.’” Many of the poems slide between phonemes, pushing at the tension between definition and fluidity. This attention to sound plies the rational aspect of language, posing the question of whether or not the Erinyes are Erinyes if we pronounce them differently—it matters what you call a thing. At the same time, Nguyen’s attention to sound also engages the mystical aspect of language involved in chant, spells, and incantation. How would one call upon the Furies if one did not know how to say their names? How would one heed Samuel Beckett’s advice to “Fail better” if one wrongly remembered his phrase? The title of the book, as the typesetting of the cover highlights, also plays with this aspect of listening to language for its mysteries, but in a numerological way: Violet Energy Ingots: three words, of six letters each.

While the book includes a poem to Orpheus and numerous nearly mythological male figures such as Pound, Shakespeare, Tagore, Spicer, Whalen, and Machiavelli, these men feel like absent or returned fathers, (“I was born in the river / I have never known you Father”), and perhaps even a wry feminist take on the muse tradition. They are significant but peripheral, rather than at the heart of the book, which is dedicated to “Aphrodite, deathless and of the spangled mind,” (and thus to Sappho, whose line Anne Carson translates as “Deathless Aphrodite of the spangled mind”) and favors fierce goddess figures: Aphrodite, Venus, Eve, Hatshepsut, “Goddesses that ate the earth,” Diana, the Queen of Heaven, and the Queen of Swords. And like “Haunted Sonnet” many of the poems put dream in tension with waking day, attending to the quotidian before spiraling into a “morning dream with ghosts”; “Meet me in a dream bed”; “dream of childhood friend,” and so on.

It might be tempting to read these oscillations between the rational and the enigmatic as registering a flatness inherent to the twenty-first century world, where the sacred is commoditized along with the political. While this is certainly an aspect of the book’s texture, Nguyen’s juxtapositions push the technique further. We see this in “Haunted Sonnet’s” final couplet, one of the most pressurized in the book, which couples direct question (“She said, ‘What do you know about Vietnam?’”) and enigmatic answer (“Violet energy ingots Tenuous knowing moment”), inviting the reader to consider not only the value of the enigmatic answer (the value of the non-rational) within today’s context of politics and culture, but also the straightforward question. What is being asked when considering sites of historical trauma? What are the ethical-aesthetic stakes entailed by this type of exchange?

It is important to note the dynamic Nguyen establishes: the question, here, is asked by the “she” of the poem, who we know to be in a precarious state: she is the “not-dead woman” who is on her way to the “incinerating garbage chute.” “She” is someone the poem’s “you”—who feels most like the “you” that is the self talking to the self, but perhaps is a more general “you”—is supposed to save. “She” is the ravaged mother goddess, the “Forever fought doll,” the one in need of Furies to avenge and revenge the wrongs done unto her by history and culture. She is our ethical imperative. We are responsible to her—responsible for, at the very least, answering her question, “What do you know about Vietnam?”

This question, we notice, is not framed as a question but rather as a statement (she “said,” she did not “ask”). This gives the exchange a tone of accusation, of demand, and creates the sense that this “she” possesses first-hand knowledge of Vietnam, both the country and the war. One response to this question would be to present a cinematic narrative of Vietnam, a personal and historical story that Nguyen, whose author-note states that she was “born in the Mekong Delta and raised in the Washington, D.C. area,” could certainly tell. Nguyen, however, answers otherwise with “Violet energy ingots Tenuous knowing moment.”

Enigmatic, lyric, oracular. How are we to process this answer? Do we read it as a refusal to answer or an abundance of answer—a “loss of meaning turning into a necessity of meaning” as Robin Blaser writes of Spicer, Poe, Mallarmé, Artaud, and Duchamp? “Tenuous knowing moment” reframes and qualifies whatever meaning and knowledge is available in “violet energy ingots” as tenuous—slight, insubstantial, a thin knowing moment.

That “Violet energy ingots” is also the title of the book deepens and complicates the response. It cannot be explained away solely as a momentary dip into what is beyond-sense, but must also be thought of in terms of the book itself. The poems themselves are violet energy ingots, a series of tenuous knowing moments that eschew the monumental gestures of narrative, polemic, or other familiar forms our cultures have made to mark modernity’s abuses of power. Monumental gestures that give us something to say when asked for an account.

Instead, the poems take up the work of showing the way that the very fabric of the daily, of language, and of our selves are marked by historical trauma. This is seen in the work’s formal fragmentation: punctuation marks have been replaced with the white space of absence, of aporia. The fragments, while assuming the feel of the daily—almost of the mundane—are at the very same time “Tenuous knowing moments” that register a tear, a rip, a rend. Nguyen’s poems register this tear as a quality of everyday experience that might otherwise go unnoticed: “Where is ‘the heart?’ Hanging / above a doorway threshold a fireplace / icon full of impossible scars”; “The whiteboard says ‘Vag Bleed,’” code for miscarriage, followed by the line “I read Anna Karenina“; “Fragrant flowers white / clusters hang down / Legume family giant flower tutus // Native to Lake Erie / area not native here / Used to reclaim ‘damaged land.’”

We cannot say for certain why the oracle’s enigmatic answers were found to be so useful to the direct questions asked of them by the people of antiquity. Perhaps an openness to interpretation allowed those in positions of power to twist the meaning of the answers to suit their ends. A more optimistic thought is that openness to interpretation called upon the receiver to enter the answer, to sit with it, and to see if it allowed the seeker a new perspective. As we move farther away in time from the first-person experience of the twentieth-century’s massive traumas while noticing that the defining characteristic of the current century seems to be that we perpetuate and compound the systems of trauma we have inherited, the question of the kinds of knowledges we can hold and create becomes ever more pressing. We might consider Nguyen’s redefinition of “answer”—images and fragments that invite us to enter in and sit with them for a while. In this spirit, I’ll end with “And,” the second-to-last poem in the book, constructed of just three lines:

the plastic bottle cap in the dead

belly of the young bird

Albatross