Everything in that Drawer

David Shapiro, Joanna Fuhrman, & Elaine Equi

July 22, 2019

Elecment Series #2

I have been reading David Shapiro’s poems since I was a teenager. Long before we became friends, the lines from his mercurial and questioning poems bounced around my mind and being, becoming part of the structure of who I am as a poet and a person. Now, decades after I first discovered his work, I often think of one of his favorite stories about the architect and Cooper Union Dean John Hadjuk. Hadjuk was showing slides of his architectural drawings, and a critic asked him “Where is your building being built? Who is funding this building?” Hadjuk said, “Nowhere,” and the critic said dismissively, “Oh it’s justan idea.,” and Hadjuk replied (David likes to repeat the story using Hadjuk’s thick Bronx accent) “That is no small thing.” David Shapiro’s poems remind us again and again that there is nothing small or “less than” about ideas. A couple of months ago, I gave a long list of poets as recommended reading to a Bulgarian student of mine new to poetry. In an email to me, she wrote, “Why is this poet David Shapiro not more well-known?” I think the answer to this question is similar to the critic’s dismissal of Hadjuk. David is a poet’s poet, which means his work, even when it’s full of love, suffering, music and imagination, is at its heart also about the nature of language, about the relationship between language and representation. His work displays an acute awareness of the slipperiness of language, and how its so-called “limits” can also be a force for beauty and energy. This question about representation might be less urgent to those who don’t play and struggle with words, but for me it’s at the heart of everything that makes poetry matter. Yes, it’s an idea, but there’s nothing “mere” about ideas.

I met David almost twenty years ago, when I was in my twenties. After my first book came out, I had the opportunity to read at the Brooklyn Central Library with the late, great Frank Lima. I was reading a series of new breakup poems, and my ex, whom I had not seen in months, was in the audience. It was all very intense, and I remember wiping tears from my eyes as I read. Perhaps Frank felt sorry for me because even though it was my first time meeting him, he invited me to a dinner party at his apartment in Queens. I knew Frank was a professional chef, so of course I said yes. Frank didn’t tell me it was a boxing match watching party. I had never watched boxing, and I still have no desire to watch boxing. David Shapiro and I were the only people not watching the fight, so we had a chance to talk. I don’t remember exactly, but most likely I confessed my deep love of his work. A couple of months later, after a celebration reading at the end of my time teaching poetry to teenagers in transitional housing, I walked in a daze for an hour or two, not sure what my next job would be and feeling full of happiness and loss. In my delirium, I ran into David at the Barnes & Noble on East 86th Street. He was incredibly friendly (as he is to everyone) and we talked about poetry and art, and he told me a bunch of stories about people I didn’t know but wished I did. He asked if I wanted to interview him, which I was honored to do. The interview appeared online in Raintaxi.

Overtime we started to become friends. For years, he was the first person I sent my poems to, and he would write back emails that were like poems themselves, sometimes even rhymed, and always full of playful metaphors. His highest compliment was calling a poem “fresh.” He’d write, “so fresh, as if they were made tomorrow.” I sent him a poem asking whether he thought the middle part should be longer, and he wrote, “It will always remain a lyric unless you add 650 pages as a midsection.” On the telephone, or in our visits to Upper East Side Galleries or the Met, he would give me long lists of books to read, artists to look up, and music to listen to. I tried to keep up, but I rarely could.

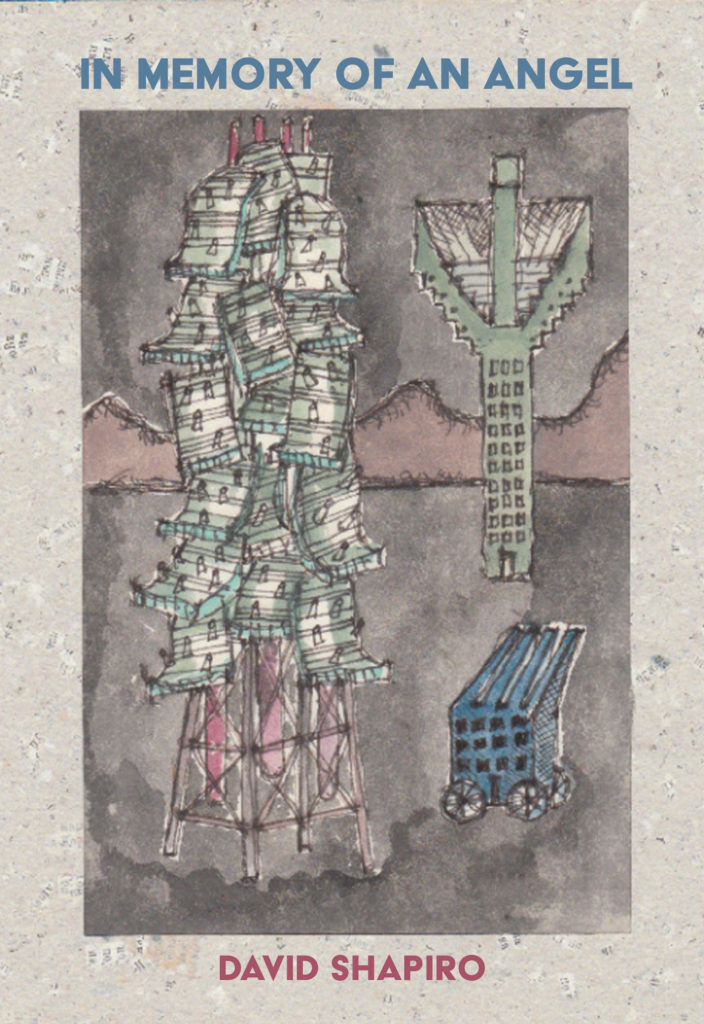

For the last few years, as David has struggled with Parkinson’s, it’s been harder to communicate, because he doesn’t email or write on Facebook anymore and sometimes is not up to talking on the phone. When I do talk to him, he sounds just as brilliant as always, but perhaps less confident in his brilliance. His most recent book, In Memory of an Angel, published by City Lights Books in 2017, is one of his best, but when I do talk to him he often dismisses it. A typical David thing to say is, “Well, not bad for a B+ poem.” But, of course, the book is full of his usual erudition, humor, music, wit, and surprise. In one of my favorite poems in the book, “A Crown for Ron,” he responds to Ron Padgett’s “Nothing in that Drawer” with a sonnet of his own. In Ron’s poem, each line just reads “Nothing in that drawer.” I have always thought of Ron’s poem as a Pop Art sonnet manifesto about the beauty of form at its blankest; like a Warhol silkscreen, Ron’s poem makes us confront what emptiness feels like. Thinking about Ron’s poem now reminds me of a time when I went with David and some students of ours to see Christo and Jeanne Claude Gates in Central Park. As we walked along the orange repetition of the installation, David started quoting Aram Saroyan’s poem “Crickets” which is just one word repeated “crickets.” As David, slowly repeated the word in what I think was supposed to be an imitation of Saroyan, we all started laughing hysterically.

David’s poem rewrites Ron’s so that the drawers are not empty; we find something of value in each one from “a blind chrysanthemum” to “broken neon geometry.” Each drawer is a window in a Jewish Surrealist Advent calendar. What makes the poem so beautiful is not just its implicit argument against the perfection of Ron’s version of post-modernism, but also the range of imagery and emotions. Each line is full of evocative—or, as David would say, “fresh” juxtapositions. As lyric and playful as the poem is, there’s a balanced menace to the imagery: Buster Keaton is attacked by the U.S. military, Borges is taught English by a gangster. My other favorite poem in the book is a villanelle called “Gratuitous Orange” that plays with rhymes for orange, the one-word people say is impossible to rhyme. Other poems are more narrative than the poems in his earlier collections which gives the reader a glimpse into David’s poetics and friendships.

In the era of #MeToo, when more and more women are sharing their horror stories of male mentors, I am increasingly grateful (and aware of how rare it is) to have found a male mentor who was always generous, respectful, loving and never inappropriate. I remember David complaining about the sexism of his generation and how often after dinner the male poets would sit in one room while the wives, some of whom were poets themselves, would go off to the kitchen to clean up. He would often ask if I thought a line of his was sexist or objectifying, and I felt comfortable enough to say if I did. He was always supportive of me as a poet and a person. We spent hours on the phone talking, because, as David said, “Gossip is a form of protection.” His friendship gave me permission to be a poet even when devoting my life to poetry felt like a completely crazy thing to do.

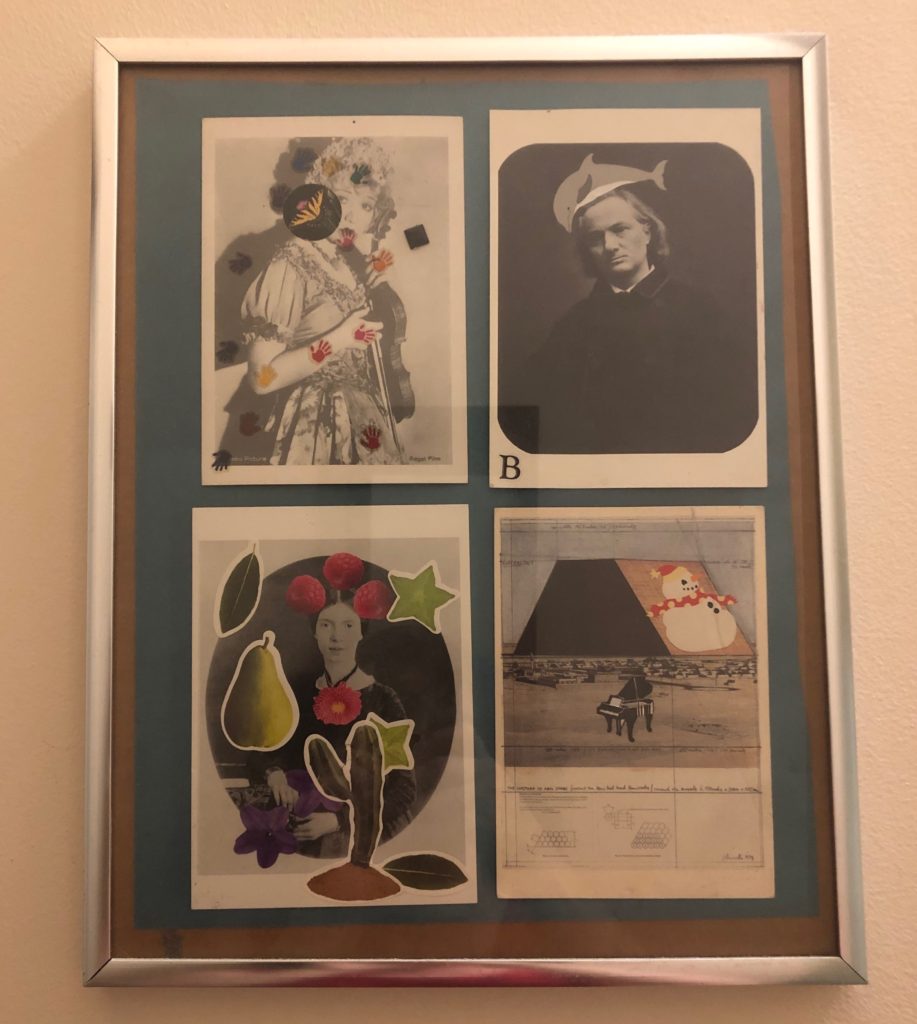

Elaine Equi is also a close friend of David’s, so we thought it would be meaningful to write a collaboration as a tribute to him and his most recent collection. David is well known for the beautiful collages he makes out of postcards and stickers. If you visit my Brooklyn apartment, you’ll see them all over the walls. For our poem, Elaine and I emailed each other photographs of the collages we owned and found other images of them online. We picked images we felt inspired by and wrote lines (or two or three) for each one. As we worked, we emailed lines to each other, and each riffed on what the other had written. We were inspired by David’s own poetry as much as by the images. At the end, I pieced the lines together of our poem “Dear David” and made a video out of it. I wanted to use a piece of music by the Viennese composer Alban Berg, because the title of David’s most recent book is a reference to the composer’s Violin Concerto. David would probably find it funny that I wanted to pay tribute to Berg, because I kept telling him that I liked his manuscript’s original title, Cardboard and Gold, better than the title he ultimately chose. David says Cardboard and Gold sounds “too New York School,” but as a devotee of the New York School and a music novice, I love it.

I was honored to be able to work with one of my other poetry heroes, Elaine Equi, on this project. I hope that our poem will be seen as a tribute to David’s work as a poet and collage artist, as well as a great person and friend.

—Joanna Fuhrman

*

TALKING TO DAVID SHAPIRO

In person or on the phone,

even casually,

is a bit like reading his poetry.

His loquaciousness is legendary,

drawing on a pantheon of artists,

philosophers, and mystics,

not simply to make a point,

but elevate the entire conversation

and up the ante for trading lines

that juxtapose the silly and the sublime.

In other words, he doesn’t save

his brilliance just for the page.

He shares it; he spends it.

David also loves giving gifts.

Almost every encounter

ends with him passing along

a poem, book, or picture —

something, hopefully, to inspire you

to make something new from it.

Which is why I jumped at the chance

to collaborate with my dear friend,

Joanna Fuhrman, on this project.

It was fun to immerse ourselves

in David’s collages — and then

thanks to her editing, watch them

come alive in such a cool and

literally moving way.

— Elaine Equi

*

Elaine Equi’s books include Sentences and Rain, Click and Clone, and Ripple Effect: New and Selected Poems (all from Coffee House Press). A new collection, The Intangibles, is forthcoming in November of 2019. She teaches at New York University and in the MFA Program in Creative Writing at The New School.

Joanna Fuhrman is the author of five books of poetry, most recently The Year of Yellow Butterflies (Hanging Loose Press, 2015) and Pageant (Alice James Books, 2019). She teaches creative writing at Rutgers University and Sarah Lawerence Writers Village.

The author of ten previous books of poems, as well as monographs on John Ashbery, Jim Dine, Jasper Johns, and Mondrian, David Shapiro is a member of the second generation of New York School poets. A child prodigy on the violin, he went on to become a literary and art critic and teaches at Patterson College and Cooper Union. He holds a Ph.D. from Columbia University and has received awards from the Merrill Foundation, the NEA, the NEH, and the Graham Foundation.