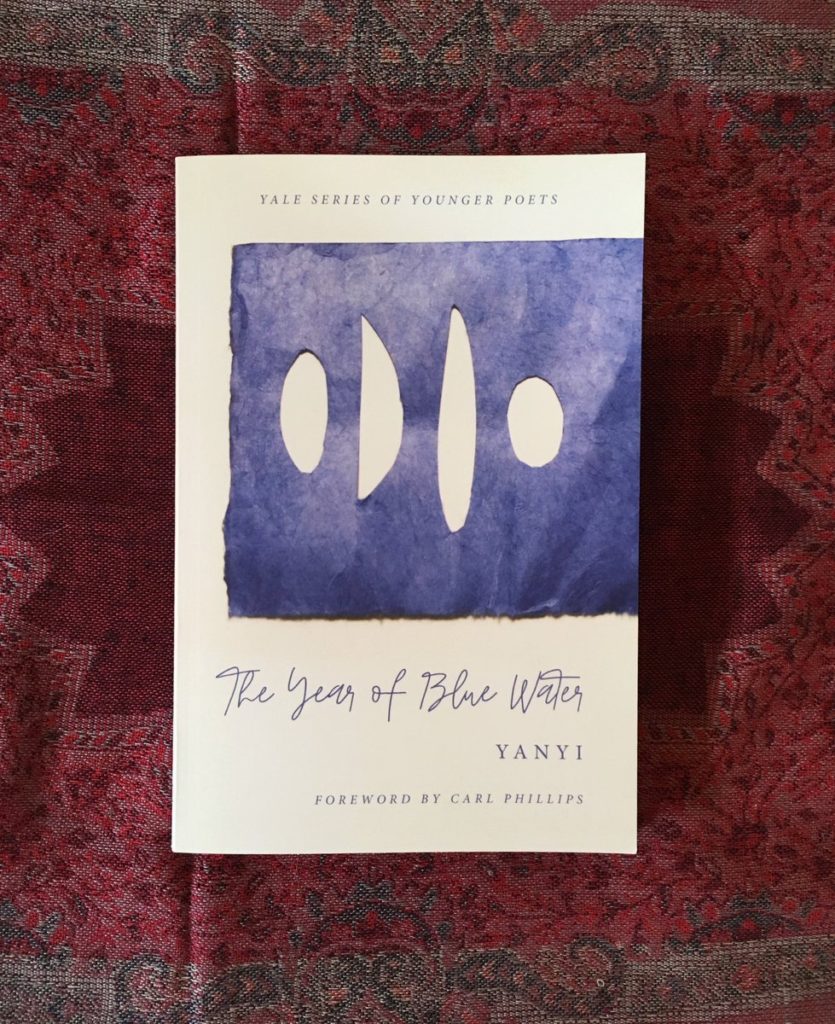

A Story of I, Self-Conscious Me: The Year of Blue Water

Yanyi’s debut collection, The Year of Blue Water, released this year by Yale University Press, is a book about the self. It’s told primarily in short prose bursts that could appear as vignettes, meditations, references to letters, and conversations about writing. It reads like an introduction to the poet, Yanyi. As in, “Let me introduce you, reader, to an Asian-American, queer, transgendered immigrant poet who lives in a big city. He’s trying to understand who he is.” The poems are engaging and thoughtful. Their voice feels so close to the poet. They lure me into believing them as an earnest exploration of self. But, then, I’m not sure I should accept that reading. Not that the earnestness feels melodramatic or performed. Each page pulls me into Yanyi’s life, engulfing me in life-feelings. Part of my reading experience wants to dwell in those feelings. There are so many layers to Yanyi’s life, it would seem life makes them complicated enough. But there is more to these poems. They are constructed, and, as Yanyi indicates at various points, he is aware of this constructed quality.

In fact, think of The Year of Blue Water as a commonplace book from the 17th Century. It reads like a series of brief impressions recorded for posterity. They range from the humorous to the casual to the very personal. On one page, he might be telling about his friend Kate, who is making a podcast that will feature other people named Kate. In another section, he tells a story from before he transitioned, when his mother could not accept her child, who was then her daughter, wearing a pair of oxford shoes. As the book relates it:

At the foldable table in my new apartment, she asked me if I was gay, which I had told her ten years ago but she didn’t believe me. She asked me if I was gay, and I didn’t say anything, but I cried. She threw away the shoes and then we had dinner. When I did the dishes, I had to empty the rice onto my shoes and I never saw them again. (26)

This story is just heartbreaking. And it’s made more so by its unexpectedness. This prose piece starts casually, “It was graduation, and I had already said goodbye to so many people” (26). The events leading up to this climactic ending are told with incisive efficiency, enveloping the reader. The narrative is saturating, and it leaves the impression that this story of self is the book’s primary concern. But there are also signals that the book is about how a story should be read. His friend Kate’s fascination with other Kates, for instance, something visited a few times in the book, leads the writer to tell when “a man started calling for me because I had won a raffle. Another Yanyi appeared several feet above me and I had to change how I saw myself distinctly. I was never unique; I was just made to feel that way” (9). On one hand, this is common revelation for young adults. Everyone, at some point, realizes they are not the center of the universe. But this particular piece is “a note to ask Kate why she is starting her podcast” (9). And though this “note” appears so subtly within the piece, it contributes to a larger trend where he talks about writing as a method for understanding himself.

In the piece preceding the story about his mother and the shoes, Yanyi talks to a friend who had just taken a class with Carolyn Forché in Greece. The friend tells Yanyi he should follow Forché’s general advice to keep a notebook. “You recommend that I start one. I agree but it takes me another six months to try” (25). The story, then, about his mother and the oxford shoes in the trash becomes more than that story. Its position in the book also has at least the hint of a first entry in this writer’s notebook. It’s the interlocking relationship between writing as means for personal discovery, and actual personal discoveries I feel in the book that I find fascinating. Toward the beginning of the book, Yanyi writes about his friend, Michelle, observing three I’s appearing in his work.

Michelle says I have three I’s: a diary I, a lyric I, and an I masquerading as a you. Michelle says the diary I is not the strongest I, the politics of which distracts me for weeks until I come to realize that I want to know who I’ve been talking to. In all instances, I am myself talking to myself. At least, I mean to. (3)

Like the story involving his friend Kate, I feel enveloped in the actual friendships that populate Yanyi’s actual life. It’s even possible to pull together information from the book’s acknowledgments and Google to learn the Michelle here is Michelle Meier. But is this important? Only that Meier is another young poet who worked with Yanyi at Foundry. And this knowledge might help to complicate my intimate understanding of Yanyi’s life with authentic fact. The factual adds intrigue.

And fallibility. Not only in the sense of “Who is this Michelle? And what does she know about Yanyi’s first person usage?” but also Yanyi, as a writer, sorting through someone else’s observations about his style. In fact, even as it tells the story of Yanyi’s interaction with Michelle, it also draws attention to Yanyi’s position as the writer of this piece. And it highlights my struggle in reading The Year of Blue Water as either earnest story of Yanyi or self-conscious, ironic construction of self. Should I be reading Yanyi’s record of an actual person’s comments on his poems as an added layer of subterfuge? A further sophistication of the ironic? It feels too earnest for that. But Yanyi is often signaling to me he knows it is “too earnest.” In fact, I am left using Michelle’s own observation about which “I” might be the “I” of this piece. It would seem to be a “diary I,” making another entry in his commonplace book to describe Michelle’s comment. But then wouldn’t the “diary I” have more to say? The quoted portion above is the full extent of poem on page 3. The next page starts, “Frank O’Hara’s ‘Morning’ is the first poem I consciously memorized. I am writing it in Wei-Ming’s letter…”

And which ‘I’ would Michelle say Montaigne uses? Which is another way of asking what would be the identifying characteristics of a “diary I” versus a “lyric I”? And what in the world does “I” sound like when it’s “masquerading as a you”? I don’t think this poem really cares. At least for my reading, this poem is part of the book’s opening move to confuse and blur and obscure the mode of each prose block. This poem is part of the strategy to lure us into that personal story of self, or at least the tone of a personal story. “Diary I” can be so seductive for a reader. And the book’s conscious use of it marks an interesting stance between personal and construction of the personal. “Diary I” would seem the most appropriate “I” for a book populated with many personal and intimate observations about family, gender queering and transition, therapy, and race, interspersed with notebook entries about specific poets and their thoughts about poetry. And here I consider the dilemma implicit to the book. Is it a story exploring the self, or is it an ironic, self-conscious construction of “I” gesturing towards his uncertainty about the book’s form? The book is so involved with self, isn’t it enough to just listen to “diary I”? Or perhaps the real argument here is for “lyric I” that leans heavily on an arc of self-reconciliation. But, then, how to account for self-conscious constructedness? Might irony be the most apt account of the self of this book, especially given its deep investment in transition—gender transition and psychological transformation, in particular. Under the banner of self-consciousness, I read that the poems prefer not committing to any one “I.” And so, for my reading, I wonder, what is the relationship intertwining earnestness of telling about the self and self-consciousness of writing as an act acted out by self? At the very least, it is but one of the ways a reader can be left in the agony of Between.

A sensation which is most palpably drawn out in the opening poem of the book, “Dream Diary,” especially at about line four, where it starts methodically moving the poem forward through undoing types of actions—a point establishing as ambiguous a space as it sounds like.

What you touch will come

to life: a whole room sprung in the backward words

of people untalking to you. Walking reverse with such

confidence until you reach another room. There stands

this person who is also a talisman. In the dream,

it doesn’t matter when they loved you.

There is this indeterminacy in the poem that feels like it shouldn’t be so indeterminate. There are concrete references like a room, people, another room. And yet the undoing of sense here seems to have such concrete intentions. It makes me think of the strange sensation I feel while watching the dream sequences of Twin Peaks, when Agent Cooper is in the red room, and everyone is speaking in reverse. But Cooper seems to understand. I think often whether Yanyi’s opening poem, especially the fact it’s one of only a few verse poems in the book, should guide me either toward that telling story of “I” or ironic, self-conscious search for form. Ultimately, I credit it with not registering one over the other. It keeps me as a reader in that space of Between, and maybe it’s recognizing the paradox that attends any notion of personal resolve or balance. Oh, so you’ve found stability. What is that in this world we’re living in? Why would you call it that? What comes after that?