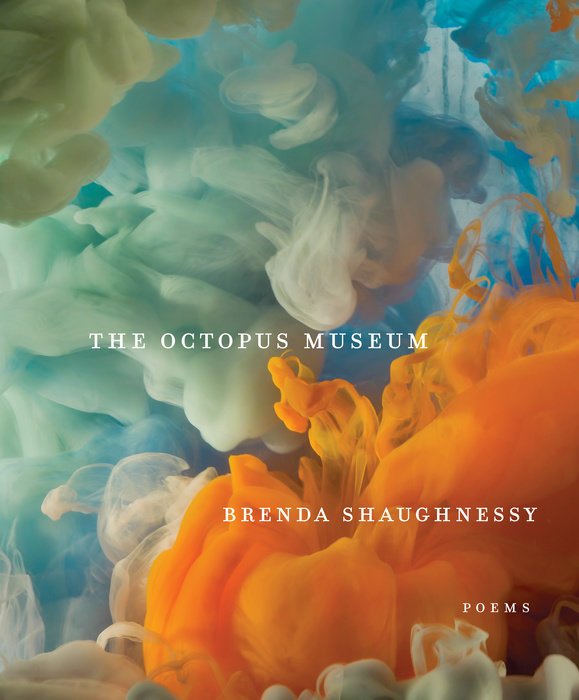

Two Reviews of Brenda Shaughnessy’s The Octopus Museum

Brenda Shaughnessy

Alfred A. Knopf, 2019

Reviewed by: Sarah V. Schweig and John Spiegel

November 27, 2019

––––A Poetics of Fear––––

Most of the poems that comprise the The Octopus Museum — Brenda Shaughnessy’s fifth book, which comes just three years after her last, marking the shortest span between any of Shaughnessy’s book publications — take the shape of lengthy and sometimes chaotic prose poems, a sharp departure from the tight musicality of her previous work. Why this change and why now?

The Octopus Museum presents itself as a book very much of its time; Shaughnessy has linked the genesis of this book directly to the election of Donald Trump.[1] Much of the book documents the fears and speculation that immediately began to arise on the Left (and elsewhere). This is clear, at moments, explicitly: “We hated ourselves,” writes the voice of a character who is writing letters to humans from the future. “We chose evil, elected it, protected it, let it maim the animals, steal the land, drop the bombs, poison the water, terrorize the children, fund the greedy, and squander every last chance.” A loose narrative framework — a dystopian world in which octopodes have taken over — tries to balance out these bursts of the extremely literal.

But what is supposed to be an imagined world often feels like mere scaffolding. The lengthy poem “Are Women People?” (which presents itself with an italicized introduction: “A report commissioned by the COP’s Department of Human Studies. In the interest of anthropological authenticity, cephalopod researchers utilized only methods and modes used by humans themselves, in their various legal, academic, and socio-cultural institutions. To the best of our ability, we worked within their language and wielded their tools in order to better understand their mysteries, and how to serve mankind’s legacy. —the authors”) attempts to explore personhood through an imagined cephalopod bureaucratic report, but ends up sounding as human as a middle-school kid’s research paper:

To begin to understand how to answer the question we must define the two terms: women and people. People is a broader term than women. Women are a subset of people. Women are a kind of people.

People are not a kind of women.

At this moment someone will always say: men are also a subset of people! It goes the other way, too! People who need to interject that point are usually men. When you hypothetically posit the word women as a term that includes men (logical, as the word men is already there within the word women) in practice the terms lose all meaning.

It goes on for six pages this way.

Even the more personal poems show this tension between the stark and dreadful facts of our time and attempts at imagination: In the shorter, two-page poem, “I Want the World,” a poem in a mother’s voice about her young daughter and her desires and complaints (chicken nuggets, dolls, Legos):

She was complaining, as usual. She was hungry. She was tired of traveling.

Her complaints were especially unpleasant since they only pointed up how innocent she was of how bad everything could get. The Legos are boring? Imagine no toys of any kind.

The chicken nuggets are too hot? Just wait. They’ll cool and by then, I hope she can learn to like lizard blood and shoelace chewing gum, because that’s what’s coming.

…

One of these mornings I’ll say goodbye, a routine goodbye when I go to the FedPlex warehouse to work or pick up my rations, and in my absence she will lose that thread, come to fully understand what she wants is impossible in our world.

All of it, any of it, the tiniest thing, impossible.

Some readers will find these inventions entertaining. But the question is whether Shaughnessy’s documentation of our timely fears in The Octopus Museum give us catharsis. Does it offer an imagined dystopia that’s wondrous and absorbing enough to give us a way of thinking through our moment? Or does one undercut the other, and vice versa, at every turn, leaving us in a limbo state, somewhere between documentation and a half-baked sci-fi fantasy, nowhere near the pleasures and redemptions that can only come from a real work of art?

You may guess at my own answer. But I want to go further in trying to understand why the result of this experiment feels unsatisfying.

***

On the one hand, we have poetry as documentation. Sure, poetry, like artifacts in a museum, can provide documentation — but so can op-eds, articles, books of prose, photographs. On the other hand, we have poetry as purveyor of an imagined world, something that the art form is in a unique position to do — but this imagined world in The Octopus Museum never feels fully committed to. It seems to come in where the pervasive and literal documentation threatens to obscure any attempt at becoming art. I read this as the result of one pervasive anxiety running through the book as subtext: How can we even think about something as lofty as creating art when we are ensconced in the fractured postmodern horrorscape that is the world since November 2016?

Most of the poems in The Octopus Museum are sharply reactive — they document fear and the speculation that comes from fear, imagining worst-case scenarios and then recording such imaginings: “Anyone who practiced their art did so secretly, and we all learned not to talk about our dreams, those visions, which could be misunderstood and burned alive. We gathered on hillsides and watched the green glow, each of us exploding with poetry silent inside.” The book takes sociopolitical regression to be not only possible but a reality already well on its way (as it may well be), but also shows its limitations, many of such whimsical imaginings fall back on bare brute facts, leaving us somewhere between the utterly literal and the poetic possibility of transcending through the imagination:

Black children were killed in broad daylight, in parks and streets and in houses and churches and cars. Especially in cars. The law said it wasn’t allowed, but it was expressly allowed, encouraged, unpunished. The law said this was the law, each time a person chose to do it. These were not accidents.

This was Before, and we’re almost certain it is the same now as Before, only now we don’t know the laws. They keep it overtly secret now, as they think we’ll think there was no before. It’s not just black children anymore, it’s everyone.

The imagined possibility of another reigning power actually undercuts the literal travesty of black children being killed in our actual political moment. What do we take away from this, exactly? That eventually everyone will be killed arbitrarily when the regime of tyrannical cephalopods take over? OK, sure.

The Octopus Museum presents us with many such limbos leaving me, at least, shrugging, “OK, sure.” These limbos — between poetry and prose, reality and imagination, irreverence and sincerity — made me question whether such closeness to crisis, such documentation and reaction to fearful reality, necessarily cancels out a poetry’s potency. One review of The Octopus Museum questioned whether these poems are preachy, and then quickly followed with the question of whether we deserve poems that aren’t preachy.[2] These aren’t quite the right questions — the worry about preachiness and what we can possibly deserve (from poetry!) operates in the same problematic and guilt-ridden paradigm that reads poetry as a subgenre of an op-ed — but I take these questions, if misdirected, to point toward the problem I have been discussing: how to think about poetry that reacts so immediately to the facts of its time. The question shouldn’t be whether these poems are preachy but whether they do justice to the endeavor of trying to create that most impossible and complex thing that is a work of art.

The trouble with fear and reaction is that it leaves little room for imagination. “This poem I stole from my fear, my endless fear,” Shaughnessy writes in one of the two poems in the book that I liked, “Nest.” And why did she have to steal that poem? Because fear wants a reaction, fear is self-assured enough to moralize, to cut itself off, to group itself with those who are like-minded — what does the audience for The Octopus Museum feel other than the same concurrent fears? (Hence also why the question of the book’s preachiness is moot.) In the poems Shaughnessy hasn’t stolen from her fear, poetic invention often feels forced or beside the point. It’s at these moments when Shaughnessy seems to forget her own profound question, which she poses in “Thinking Lessons,” the other poem that I liked: “What are the most important questions, other than this one?” When Shaughnessy also says “I love what’s sublime—beauty greater than my sense of beauty,” I want to believe her. Shaughnessy may well love a beauty greater than her sense of beauty—but she may not have given herself time or space to access it.

***

If so much of this book is a documentation of fear and reaction, what’s going to happen when the pendulum swings in another direction, whether that be in 2020 or 2024? What’s going to happen if we feel a bit more self-assured that progress toward universal human rights is still possible and that we can intervene in climate destruction before utter disaster? Will we still feel the same sense of urgency as preserved here in The Octopus Museum? Will these poems still matter to us?

I’m thinking of a passage I read recently from Natalia Ginzburg’s Family Lexicon, where Ginzburg is reflecting on life in Italy immediately following the fall of Mussolini:

At the time, there were two ways to write: one was a simple listing of facts outlining a dreary, foul, base reality seen through a lens that peered out over a bleak and mortified landscape; the other was a mixing of facts with violence and a delirium of tears, sobs, and sighs. In neither case did one choose his own words because in one case the words were inextricable from the dreariness, and in the other the words got lost among the groans and sighs. But the common error was to still believe that everything could be transformed into poetry and words. This resulted in a loathing for poetry and for words, which was so powerful it extended to true poetry and true words.[3]

Visiting this figurative museum gave rise to many questions that I believe to be most important for poetry right now. Like any exhibit of disparate objects, The Octopus Museum provides us objects which make these thoughts possible. But a mix of delirium and the dreary reality of which Ginzburg speaks is all pervasive, and the attempts to escape the one through the other often fall flat.

[1] In an interview at LitHub, as well as in the book’s acknowledgments.

[2] Elisa Gabbert’s review of the book in The New York Times.

[3] Ginzburg, Natalia, Jenny McPhee, and Tim Parks. Family Lexicon. New York: NYRB. 152-3.

––––A Warning Sign From Behind the Glass––––

Brenda Shaughnessy’s The Octopus Museum is a post-apocalyptic prose poetry book. This description might pique some people’s interest, and this could very well be one of the more interesting poetry books so far this year. However, this combination of words certainly isn’t going to interest everyone. In both cases, though, it’s beneficial to redefine the term “post-apocalyptic.” Most of us probably picture devastated wastelands, a tattered society, and everything in sepia. Most importantly, there’s typically one climactic, horrific event that drives apocalyptic narratives: a nuclear war, alien invasion, etc. That’s where Shaughnessy’s interpretation differs. Rather than one single, significant moment serving as a catalyst for the destruction of the world, The Octopus Museum is about the ongoing destruction of the planet through pollution and global warming. Primarily, the story focuses on a mother and her family traveling through and surviving in this new world people have created, though poems often take on different speakers: for example, the octopus overlords that now rule the world since people have destroyed their home, or Ned Grovers, a former politician writing to humanity. And the feelings of guilt for causing this doomsday are immediate. In “Sel de la Terre, Sel de Mer,” the speaker recognizes her role, and every individual’s role, for the end of times in which she’s living. She addresses her new cephalopod rulers: “Oh funny, runny little god who lived in the sea we cut to ribbons! Tell us the big / story with your infected mouth. Tell us the big story is so far beyond us we can’t / possibly ruin it, but you’ll let us listen if we sit way in the back, quiet side creatures / and marginal beasts” (34). The speaker goes on to confess and apologize: “We don’t know what we’re doing.” Later in the poem she observes, “If you’re at the center the center might hold” (35), as if everything people touch is doomed to fail, reflecting the idea that people are inherently flawed. A harsh, but perhaps realistic view of human history.

This personal accountability for the dark tragedy at hand is shown through more than just the mother figure, though. In “Letters from the Elders,” Ned Grovers, a former mayor of Peterborough, New Hampshire, addresses all of humanity:

Dear Humans,

One word: plastics.

I won’t withhold everything I’ve learned. I’ll tell you plain. You will miss

plastics. (46)

The message here is clear: every one of us has a responsibility for what has happened, for what is happening. Garbage collecting in the oceans, plastic bottles running in rivers, every piece of litter on the side of the road – corporations, companies, and countries are all responsible, but we as individuals will be held accountable as well when the inevitable consequences come knocking. At the end of the letter, he says:

We thought we were throwing it “away” until “away” threw itself back at us.

This was our near-destruction, and it was well-deserved. We served it first. Some

people like to point fingers but I’d like to point out that our fingers are basically plastic. (46)

This planet is our legacy, and how we leave it is how others will inherit it. This dynamic becomes clear in the mother’s interactions with her daughter, especially because the events of the book seem so close to the present, close enough that the mother remembers what life was like before, and is constantly comparing her reality to her daughter’s fantasies. In the poem “I Want The World,” the speaker says, “Her complaints were especially unpleasant since they only pointed up how innocent / she was of how bad everything could get. The Legos are boring? Imagine no toys / of any kind” (22). But the feeling is despair, our inability to protect and provide is what we’re left with. “Blueberries for Cal” is a particularly poignant piece, simple in its composition, leaving a bad taste in our mouths:

Sometimes I can’t bear

all the things Cal doesn’t get to do. I want to curse

everything I can’t give him.

Admire/compare/despair – that’s not the most real

feeling I’m feeling, is it? (54)

Weaving all of these emotions together is a prose poetry structure unlike Shaughnessy’s other work. But while the majority of the poems utilize long lines going all the way to the right margin, they’re also fairly short stanzas, typically 2-5 lines total, often near sentence length. All of this might be fitting considering the scope of The Octopus Museum. This book isn’t just exploring an idea, not just posing questions, not merely pontificating in writing; it is telling a story. And the prose format seems to highlight this – Shaughnessy’s writing has always been a combination of poetic language and essay-like ideas, but never has it been so blatant and in-your-face. Of course, she’s not afraid to break her own patterns. At times, it’s subtle and short, as in “The Dessert I Didn’t Have.” Other times, it’s long winded and trying to be noticed. This juxtaposition is never more pointed than in “Are Women People?” This piece, broken into six separate sections, is a legal investigation performed by the Cephalopod’s “Department of Human Studies.” Specifically, the second section, “Queries: How Do We Define People,” is the most visually distinct poem. Shorter lines and heavy anaphora create a stark contrast to surrounding poems, and the inherently political nature of the topic makes for some of the most charged moments in the book, creating a rapid-fire, interrogation style poem. The speaker asks:

What about future people?

Are children people?

Are babies people?

Are unborn babies people?

Are fetuses people?

Are embryos people?

Are zygotes people?

Are sperm people?

Are ova people?

Are people’s plans to have children people? (58)

It is no accident that this poem occurs at the most climactic moment in the book; in fact, it is the structure of this poem that makes this moment so climactic, so energetic, so emotionally charged. It’s as if Shaughnessy is pulling back the curtain of the poem and is showing all of the raw emotion behind her writing before composing herself again and returning to formal structures for the remainder of the book.

At other times, though, Shaughnessy seems to be playing with the potential of the form, with potential textures, topics, and sonic possibilities. As already seen, she handles the weighty, the emotional effortlessly, but her writing also contains trademark Shaughnessy humor. And at other times, such as in “Our Beloved Infinite Crapulence,” Shaughnessy is playful with her language: “The wet slit lit up / and cut down the middle, a little spit, lip a little bit split. Love in the Candle Shop: / Wicked” (44). Perhaps what it does best, though, is make her language accessible. Yes, there are moments, like in “Thinking Lessons,” of dense, reduced language that one expects in poetry (“No one is one. / No one is no one”) (44), and even the associative leaps more common in modern works, as in “Gift Planet” (“Car feels like a pod, an exoskeleton, a place inside me. Car short for ‘carapace.’”) (9). Yes, at times there is heavy enjambment or rhythmic shifts, as in “Are Women People?,” which keep the reader engaged and push the reader forward (“These documents are and records are proof that dark-skinned people, brown / people, people who come from Countries of color…”) (61). But on the whole, the driving force is a prose line that gives the impression of the poetic line. To some extent, this is the exact purpose of prose poetry. Shaughnessy isn’t trying to change that, just to explore it. For as much as The Octopus Museum is a narrative driven message, it’s also an experiment in form. If form is an expression of content, then Shaughnessy seems to be saying that this particular form can express any particular material. The political, yes; the eco-critical, yes; the relational, yes; the feminist, yes; but even the lighthearted. And because she handles so many different issues, it’s as if she’s backgrounding the form and foregrounding her content – the prose poetry becomes almost invisible behind her imagined narrative.

But at its core, this book is a warning sign. Or if it’s too late, then a prediction. And it’s certainly more of a response to American culture than other works by Shaughnessy. The family relationships are here, as they often are with Shaughnessy, but they take a backseat. What matters here is the relationship all people have with one another. The relationship all people have with the planet on which we live. And, because of the accessibility of her language and combination of poem and essay, she seems to be saying that it’s a message all people need to hear. For such a time as this. For such a planet as this. For such a people as this. For such a torn culture as this: The Octopus Museum is an insightful view from behind the glass.

–– John Spiegel