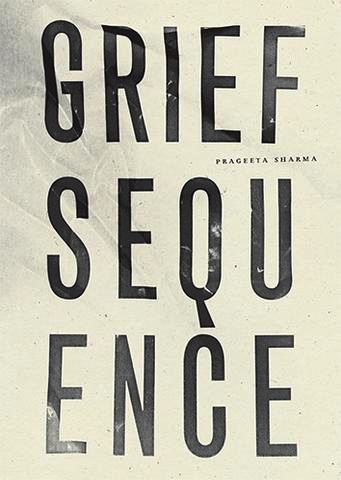

Reclaiming the Complicated: Niina Pollari Reviews Prageeta Sharma's Grief Sequence

I began reading Prageeta Sharma’s Grief Sequence, a poetry collection dealing with the aftermath of the author’s husband’s sudden death from cancer, with a bias against grief books. I’ve been reading widely in the genre (though admittedly mostly prose), and have come to find I dislike some of its conventions. For starters, grief books often seem to neatly package the grief itself into something in the past; this way, they seem to implicitly offer a lesson that makes me bristle. Grief books often, to me, read as a kind of literary self-help. They depict pre-grief existence in the hazy, nostalgic filters of a #throwbackthursday post—they give a flat glimpse at what life was like before the bad thing happened and screwed everything up. Then, with the help of time, they give the readers a new and improved narrator. At their worst, grief books even exonerate all parties from bad behavior, as if the grieving process took them out of their fallible lives and placed them onto some kind of alternate spectrum where the only objective is to read Hamlet or Joan Didion, remember the beloved fondly, and move on. Some of this, I’m sure, comes from an unfair expectation that modern life places on the grieving person—you should get over it, and if you don’t, you’re being unnecessarily messy—and some of it comes from the insistence that books need an arc and an epiphany. But it makes grief books seem formulaic whereas the grief itself is anything but.

These are the kinds of narratives that make me suspicious. I’m not looking for a lesson, or to learn how the narrator got over it, and I especially do not want to know how much better the narrator now is from having gone through the thing they experienced. I want to know how bad they still feel, and how the grief is something they still live with, even though it’s been a long time. I want to know the anger and impotence that continue to vibrate in their bones, and I want to know their failures and the shortcomings they continue to have even now, after the fact. I want to know all the ways in which they haven’t moved on. This is maybe symptomatic of me being a deeply ungenerous and biased reader—although maybe I’m not the intended audience anyway because I am a person in pain, and all I want to do is witness another person’s radiant suffering in order to feel less monstrous about my own. Maybe most grief books aren’t written for people in pain, but for the rubbernecker who wants to examine a disaster and think I’m so glad that didn’t happen to me.

I know the things I describe (the narrative structure, the epiphany, the follow-up) aren’t necessarily all relevant to poetry collections; nevertheless, this is the place I was in when I started to read Sharma’s collection. But then she didn’t ask me to read any Shakespeare or Kahlil Gibran. Instead, she wanted to know if I knew “what to do with the heart in rage.” I didn’t, so I kept reading; thankfully, she did not prescribe me an answer.

I found Grief Sequence to be largely unsentimental in the best way. The poems steer clear of the temptation to provide a beatific vision of the partnership before the loss; instead, both parties in the poems (the narrator and the husband) come across as error-prone humans, and the poems do not shy away from assigning blame, guilt, and other unbecoming emotions on top of the mourning mechanism. The husband is a bad husband at times, having carried on an affair of sorts that the narrator discovers after his death (“Hiding emotional affair til I read an un-erased text after death”). The narrator in turn can be petty, judgmental, and ungenerous toward the husband and his friends (“I remember distinct feelings of being the marginalized spouse with two selves seen from the corner of an eye by the likes of you”). This book mourns the loss of a partnership that was far from perfect, but one that the narrator and the husband had nevertheless committed themselves to. And sometimes, as if sensing herself treading too close to sentimentality, the narrator summons the figure of the husband as a way to remind herself to stay honest: “you won’t let me do any wayward effusive gestures that describe how you are mythic.” I loved this characteristic of the book, this defiant complexity and insistence on the flaw—it’s something that seems to me to be utterly respectful of the personhood of the deceased. Sharma’s narrator won’t let herself turn into a mythologizer out of esteem for the totality of the person she loved; in so many ways, this is also self-esteem.

In several poems, Sharma calls the grief “complicated.” This is both a personal admission and a clinical definition. In bereavement studies, grief becomes complicated once it lengthens beyond a “normal” period of time and takes on an intense, extended focus. The complication often manifests as an inability to move past the loss, accompanied by periods of anger, rage, hopelessness, and sometimes suicidal ideation. Complicated grief can come with intrusive thoughts that manifest themselves in everyday actions. These kinds of thoughts come across particularly in “Sequence 2,” a poem that describes, in clinical language, brain metastasis of esophageal carcinomas but punctuates the descriptions every couple of sentences with “[DEATH OR DYING]”, as if the final consequence is never far off your mind, which it isn’t. Uncomplicated grief, by contrast, is one that includes periods of debilitating inactivity but generally moves toward an integration of the loss into the routines of life—a resolution of sorts, or what would to an outside observer seem like an expiration date, a time when the mourner would finally be ready to move on. There is no set deadline by which uncomplicated grief complicates itself, though some say the period is something like six months to a year. But to me, complicated grief in the face of a partner’s loss does not sound unreasonable—why wouldn’t you have extended rage and hopelessness after the loss of someone whose disappearance from your life means a total re-imagining of your own routines? To call something like that uncomplicated would feel insulting, and the narrator’s naming her grief complicated seems to appropriately reclaim the term.

The sequentiality that the title Grief Sequence evokes is also familiar. We hear so much about the grief “process,” about its “stages,” which are supposed to make us think of distinct rooms that you have to go through, one after another, to get to the end of a finite process. But the timeline in Sharma’s book, like the timeline in grief, is one that loops over itself, like the cord on a vintage telephone. She knows the outside world insists on progress, but finds herself unable to attain it or seek it, even with the passage of time: “I’ve been sad and can’t find a seasonal sequence.” And although time keeps moving forward, it turns out the stages aren’t sequential at all; the husband keeps coming back, even when the narrator is in bed with a new lover in the last third of the book: “Do you fall into bed with us, and I have no idea of this? I’d love to think it’s so.” The husband is never gone for good, and she doesn’t want him to be. But the heartbreaking thing about the ongoing presence is that every time the lost beloved is there in the room again, it’s another chance to lose him.

There is of course still a narrative arc, despite time muddling itself throughout the book’s pages, and this is perhaps out of the sheer fact of the passage of time. The book begins with an examination of what’s left in the immediate aftermath (“So what now? I grieve. I lust for company I can’t ask for. I turn into my own madman”), and then examines the “sequences” themselves. Then, with time, it introduces the presence of a new lover, another grief-stricken person: “Because then, and suddenly, I loved again. And it arose against sequential time.” The new lover’s sudden appearance may seem outside of the grief process itself, and, as such, slightly out of place, but that’s the way this all works. Nothing happens in the order you expect; in reality there is no predictable sequence. “I think I am finally able to take some distance from this book and see it as a reflection of the stages I was in during the writing and early grieving process,” Sharma says in an interview at Tupelo Quarterly in November of 2019. “It has become a true document defining my grieving stages, for me, which was what I had wanted to do.” Even the new lover (i.e. the necessity of companionship) is a part of this grieving as much as the sadness itself is. I don’t know whether the poems in the book appear in the order in which they were written, but I will say that the earlier poems appear messier than the poems in the ending, in line with the progress of grief.

Does the literature of grief require a moment of aha? I don’t think so; I wish more books would let the many ways in which the grief lingers be the point. This book doesn’t force lessons on its reader, and I’m glad for it. I do believe Sharma gained perspective from the passage of time, but the reader doesn’t have relate to it as a sort of universal experience. This is a book of personal grief, and an account of an individual mourning a specific, sudden, sad loss—a cruel and random one from which she shouldn’t be expected to glean a lesson (“I can’t happen into its learning like it’s wisdom”). But as a work, it is also smart and rigorous. It takes on some of the conventions of grief literature and examines and questions them. I approached the collection from a surly place, but found myself with a deep appreciation of Sharma’s respect of the complication of her own process, and of the techniques she employed to get the reader to follow along.