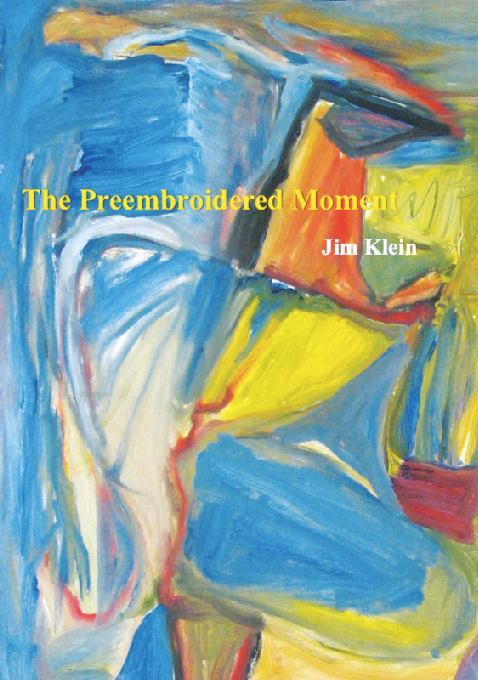

Manic Clarity: Arthur Russell Reviews Jim Klein's The Preembroidered Moment

Jim Klein leads the weekly workshop I go to in Rutherford, New Jersey, edits The Red Wheelbarrow, and is, in that regard and others, one of the chief nuclei of the Northern New Jersey poetry scene. His new collection of poems, The Preembroidered Moment, which follows at least three others, including Blue Chevies, a finalist for the Anthony Hecht Prize, is his most ambitious and daring, and that in itself is surprising because this big collection (80 poems, 130 pages) was written but not published between 1969 and 1986, a period during which he was dogged by manic disorder (“M/D”), which makes this book simultaneously a product, an artifact and a self-conscious affirmation of and identification with the crap he endured and is still surviving. It is also, not incidentally, great poetry. It is not poetry about M/D, not a memoir or a victim’s tale, not a survival guide or an analysis; it is a book of poems about humiliation and what comes after humiliation, which is not redemption but something possibly more useful, written from within the maelstrom of M/D, captained by craft, and by craft I mean both the vessel that he clung to, and the skill he used to steer it.

The Preembroidered Moment is a book that is true to both of its epigraphs, one quoting an Ezra Pound letter advising e.e. cummings to “stick to the original, preembroidered moment” from which the collection takes its title and the other summarizing the relationship between M/D’s creativity and self-destruction: “To be in the grip of mania is to experience the unimaginable, try the unthinkable, do the unforgiveable.” Klein doesn’t want to pretty M/D up with metaphors or tell an after-the-fact story about it. The disease, as Klein shows it to us, creates realities that are more surreal than even the most limber poet could portray through metaphor/substitution, and the challenge that he faces and meets is the challenge of presenting these extreme moments of disjunction and hallucination (if that’s what it is) as one would the quotidian tragedies and insights of a healthy poet. Generally the poems in this collection steer clear of metaphorical substitution, and they do so because metaphor is a distraction.

When Klein uses metaphor, he tends to embed it in verbs, where it can do the most allusive good and the least distracting harm, as when the poet is hospitalized, in the book’s second poem, “The Roommate They Have Bedded Me By,” and shut into a darkened nighttime room, he hears another man’s heavy breathing and fears for his life:

From stretched, grinning lips,

I send my name into the night.

The handshake explodes greetings in us.

The poem never leaves the darkened room to elaborate on the tense moment, yet these two sentences compress a deeply metaphorical impulse for the emotional fragility and immensity of the moment in the verbs “send” and “explodes.” “Send” embodies the notion of an emissary, advance or scout without an explicit destination. “Explodes” suggests a detonation that occurs when hand meets hand but wastes no time on clichéd comparisons to fireworks. The strangeness of the three words “handshake explodes greetings” is so dense it takes a moment to bloom, but this direct report is how Klein lets his verbs do the work of metaphors without embroidery.

And the avoidance of cliché is important to Klein’s thematic ambition to let the reader into the chaotic, terrifying, sad world of M/D, which he achieves through plain and objective report. For example, the book is divided into eight sections. The first section, twelve poems long, takes the reader through the whole cycle of a manic eruption, hospitalization, the humiliation and powerlessness of incarceration, and the slow return to a kind of equilibrium. When he is manic, in poems like “Both,” “This Roommate. . .,” “Two Orderlies,” and “Blue Ships on the Wallpaper,” Klein can barely identify other people; he describes them only by their role, or as forces acting on him: “players,” “a patient,” “this roommate,” “orderlies,” “nurses,” and, my favorite, “this plainclothes individual with tiny pupils.”

“Two Orderlies” is a paradigm of this perspective, which captures the stark and horrible fear that underlies mania. Klein describes hospital workers – “two orderlies,” “two deputies” and “two nurses/ with syringes” – taking “a woman” to be sedated. The impression that we are seeing a procession to an execution, already apparent in the two-by-two impersonality of the actors, is heightened by the way the poem is presented on the page, in a column of two-line stanzas in which almost every line is two dimeters long. The terrible, faceless inevitability of the sedation is even stronger because it is presented in a single sentence:

Two orderlies,

like matched, black

Judas goats, in white,

lead two deputies

holding hands

with a woman

and two nurses

with syringes

in a procession

to the Quiet Room.

In poems where the poet begins to come down from his manic high, people take definite form; they have names, or at least identifying characteristics. The poem “Matches” is a sort of roll call for the inmates at his hospital; the little that the poet knows about them is enough to create a portrait. “Two Men, One Dragging a Stick” shows Klein walking to the pharmacy on the hospital grounds. The two men of the title are not stick figures, he really observes them (“By their leisurely movement, / they almost seem tourists.”); and wonders about them (“But so self-contained?), and is greeted by them (“For some reason, these two/ are delighted to see me, but I hardly know them”), before moving past them.

But the genius of the collection’s first section is the contrast between the first poem and the last. The first (“Both”) begins with a frightening hallucination that leads to his hospitalization (“Pinball machines were crosses / split lengthwise, / impaled players wriggling / on their spars.”). The final poem in this section (“The Happiest Time of the Day”) ends with a game of “pretend” as, after the evening meal, the poet goes “to the head [to] watch / the sun set through / the heavy bolted screen.” He smokes a cigarette and “pretend[s] that [he] had put in / a hard day on the farm / and truly earned [his] keep.” Both hallucinating and pretending are expressions of the mind’s immense power of counterfactual imagination, but they are psychic opposites, one out of control, the other an expression of creative play; and the way that they are deployed, in plain report, with true spokenness, creates an aesthetic rather than a psychological portrait of the man inside the disease.

A bumpy journey, this book is oddly reminiscent of the early Raymond Carver, in Will You Please Be Quiet Please, but Carver was writing about characters dogged more often by substance abuse than mania, and he wrote through the mask of fiction, which is, in some ways, a dramatic metaphor, character replacing self. Klein writes about himself. The poems are crisp, dry, sometimes funny, but never comical. Klein takes the experience head on, with nothing to shield him from the direct, unembroidered experience. Maybe that’s why it took him thirty odd years to let these beautiful poems see the light of print. They tell too much to be proud of, and too much not to tell.