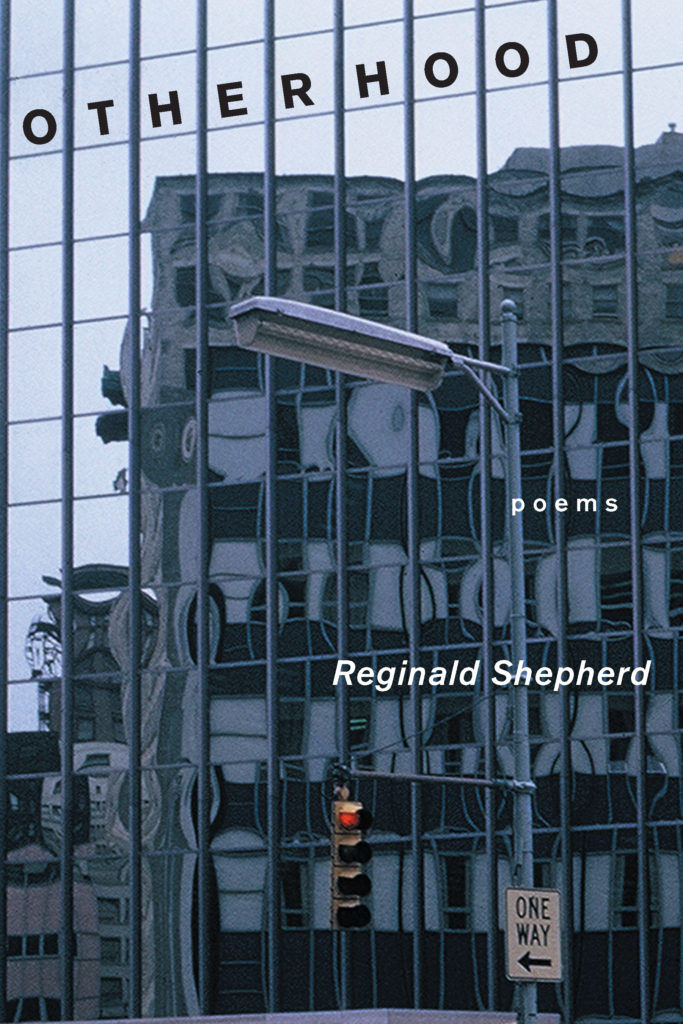

Otherhood by Reginald Shepherd

Reginald Shepherd

University of Pittsburgh Press, 2003

Reviewed by: Joyelle McSweeney

November 2, 2003

\\ The Constant Critic Archive \\

Reginald Shepherd’s Otherhood is a departure, a whole fleet of departures. More word-centric than his previous volume, these poems proceed by confident brief lines that steer the poems ever further from known shores. In the initial poem, “Reasons for Living,” an account of a lovers’ stroll by “the backwards / river, sluggish water dialects” goes first Hopkins-esque (“spilled lakefront’s / tumbledown babble of dressed / stones”) and then past Hopkins into logophilic litany. The speaker describes ‘[m]old colored water’

with a turquoise line to build horizon

out of: prehnite, andradite,

alkali tourmaline, a seam of

semiprecious chrysoprase: anything

but true emerald, a grass-green beryl,

smaragdos, prized for medicinal

virtues: uvarovite even rarer

among garnets, its crystals typically

too small to cut.

This is a sea’s weight of language built from the initial ‘turquoise line.’ The energy of this middle stanza cannot be digested by the poem, which turns its attention fitfully about before terminating in a relieved return to amped-up terminology: the lovers (or perhaps their sex organs) “stand up / erect as grass, xylem, parenchyma, / epidermis, leaf blade and sheaf.”

Though this willingness to give over to the power of words themselves results in fewer ‘well made’ poems than typified Shepherd’s Wrong, the poems of Otherhood are more daring, more ranging, more exploratory for this freedom. The flexibility demonstrated is sometimes Ovidian—various poems track Apollo, Daphne, and Eros—and sometimes sui generis. In the multipartite “Little Hands,” for example, wind-blown leaves are described first as “little / hands designing new catamites / for outmoded gods”; trees appear again and again until, in part 6, “The god fucks himself with a fig branch / above the open grave, admirer / of hopeless machines.” All this erotic energy is then catalyzed in the final section

[…]The statues sweating, overflowing

[…]cute guys in various states of disrepair

sighted from across the burning bridge,

and voices in salt water singing

“pale Gomorrah.” I walked into my ocean,

meet me under the whale.

So many referents present themselves for these lines that I cannot quite work out the ‘scene’ of this scene, or even the speaker. My best guess is that the speaker is looking on classical ruins, which are queered for him by Biblical association with Gomorrah’s ruin. Passage into the scene is permitted by the speaker’s godlike or even godly randiness; The Tempest is echoed here, and Prufrock is rewritten. The imploded irreducibility of this stanza is integral to its strength. No false arrival is engineered. The speaker merely departs again, challenging the reader to follow.

Another large-format eroto-academic success is “Wing under Construction,” which features Eros and other mythical figures, and ends with a nautical image both spectacular and intimate. The monthly apparatus of “The Roman Year” sets off its entirely elegant installments to good effect, whereas notes at the end of the book are vital for passage through the graceful but oblique “In the City of Elagabal.”

Some poems leave one wishing the academic requirement could be briefly waived. “Homology” would do just fine without its epilogue, and the lovely “Apollo on What the Boy Gave” would be more breathtaking without its botanical asides. At other times, sheer musicality tugs the reader through dense lexical passages. The reader who steers by etymology and ear through this first stanza of “Wicker Man Marginalia”

madrona taken for magnolia

sperm-scented old world

blossoming: when they saw the terraces

of white tepals, they named it

Magnolia Hill, seminal

bluff overcoming new water

will be rewarded by the available, lovely second stanza:

words break me, break

from me, branchlets

glinting gray in moon

-light, slivered green by day.

Otherhood ends with a run of striking poems that seem to offer commentary on their techniques, yet do not betray the volume with thematic glosses. A butterfly-themed poem could serve as an ars poetica for this word-fueled poetry, for the way in which linguistic ground becomes a poem’s territory:

. . . the past of the imago must be

imagined. Pyraloidea, Pyralidae, Pyraustinae,

Anania, oblique descents into

the specified, the labor of the senseslaying down tundra from Scandinavia

to Siberia

In the very fine “Littoral”, the poet-speaker reports a moment of inspiration within inspiration: “I could enter / the surplus of it, make use of / spilled exchange: […] snow under the skin, / the scorched edges of the possible / (the cold beneath the burn of it).”

In this passage, and in this volume as a whole, we recognize an electrifying, even Yeatsian, ambition. Poet and poems push to reinvent themselves, stanza by stanza, pursuing dynamism at the risk of imbalance or even dissolution. The risk is worth it. With Otherhood, Shepherd’s gifts appear, incredibly, redoubled.