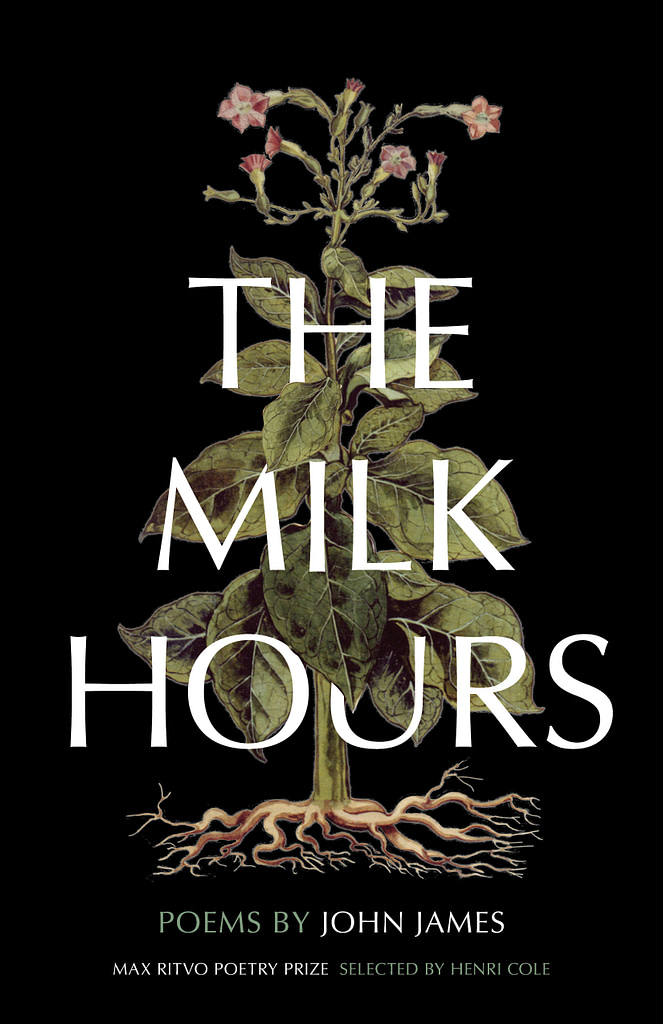

A Slower Boil: John Spiegel Reviews The Milk Hours by John James

John James’s first full-length book, The Milk Hours, is also my introduction to his poetry. Having never read Chthonic, his 2014 chapbook, I was going into his recent manuscript with an open mind. And holy cow, does it pack a punch! The manuscript centers around the loss of James’s father. And while it would be understandable for such a tragedy to dominate one’s mind, and I wouldn’t fault the author for writing nothing but poems of grief, James is quite subtle with his handling of the topic. For that reason, the book is a bit of a slower boil. James only addresses his father’s passing when there is another image to accompany it, making it seem more like a background detail than a central focus. In “Catalogue Beginning with a Line by Plato,” he surrounds this fact with a barrage of imagery:

Children’s hands in snow. Houseboats on the lake,

a red and yellow bicycle. The scent of black cedar

severed in its prime.

When my father died the nickel

wire of my throat

collapsed, snapped, twisted in air—

hung itself

limply from the column of my neck. (33)

However, in “Chthonic,” James addresses his loss: “My father’s / mouth, which I lost / years ago, speaks / from a jar on the shelf…I ask / my father why / he can’t hear. He tells / me he’s underground.” But before arriving at these final lines, James uses imagery as foreshadowing. The poem begins, “My light bulb is gone. / It was dying anyways. / The room goes dark / before I sleep” (48). This is wonderful in the way it mimics real life tragedy: something that is always there, ever present, and no matter what is in front of us, it will always be behind us.

In his review of The Milk Hours[1], Nicholas Molbert called the book an elegy, and for all of the above reasons I agree, but I think it goes deeper than that. This is a book in memory of his father, yes, but it’s also a book about life that surrounds the grieving process and how one begins again to see life beyond the sorrow of loss. In other words, if we look at the elegy like the stages of grief, the poems in this book don’t stop at depression, but move into acceptance. The title poem of The Milk Hours shows this more than others; it truly exemplifies the depth and complexity of James’s storytelling. It is dedicated to both his father, “J.E.J., 1962-1993,” and his daughter, “C.S.M.M., 2013-,” thus drawing a picture of the circular nature of life and death. James then makes a nod to Carolyn Forché’s Blue Hour, to which his book’s title alludes. James begins the poem by borrowing a line from the titular poem of Forché’s book: “We lived overlooking the cemetery.”[2] James takes this line a step farther. He lives “overlooking the walls overlooking the cemetery,” (1) showing us that his book will be more reserved, distant even, in its view of death, of the chthonic, to use his choice word.

The cemetery is where my father remains…

The room opens up into white and more white, sun outside

between steeples. I remember, now, the milk hours, leaning

over my daughter’s crib, dropping her ten, twelve pounds

into the limp arms of her mother. The suckling sound as I crashed

into sleep. My daughter, my father—his son. (1).

This section hints at his father’s death, shows the feeding of his newborn daughter, which hints at the title of his own manuscript, and alludes to images used in “Blue Hour:” The chapel, the son, the white room, the crib, the weight of a body. It’s dense with its own emotional weight while still paying homage to its source, which is in itself a picture of ideas being passed down through generations; his father to him and he to his daughter. Perhaps I’m overly sentimental to this idea, having recently had a daughter, but the concept of passing things on from one person to the next, generation to generation, has been on my mind recently.

Obviously, it’s been on James’ mind as well. “Kentucky, September,” an example of a narrative-heavy poem from the book, begins:

My grandfather stood outside smoking,

watching the migrant workers

bend over the bare furrow.

I was in the cross-barn stripping leaves

from green stalks, knowing God was cruel,

that he must be…

James confronts the concept of lineage, family, new life, and life passing all in two densely packed sentences. The poem continues by showing images of a dead goat, paralleling his father’s death:

Once we found a she-goat dead,

her belly split, and blood trailing over

an arched rock…

My grandfather took the carcass

in his arms and carried it to the driveway

where I said a short prayer.

While certainly gruesome, this scene contains an oddly gentle moment: carrying the carcass and praying over it. This could be compared to a loved one passing away, but we also carry sleeping children from the car to their bed, or carry wives over the threshold, symbols of youth and life and love.

At the end of the poem, the speaker encounters a revelation:

Then I realized this wasn’t my grandfather,

and these weren’t my hands.

All of this was a pasture resembling heaven.

Heaven was a meadow in time. (43)

James continually juxtaposes his memories and his own grief with scenes in nature, in wildlife. Sometimes nature is destroyed by the hands of people, as in “Kentucky, September,” or as in “Years I’ve Slept Right Through.”

In the dooryard

a young boy stoops to pluck

feather from feather until his hands are sore.

Other times, even in the same poem, nature fades in a more naturally occurring cycle, at the hands of itself.

On the front porch, my cat devours a hummingbird.

He beats the brilliant body with his tufted paws.

He breaks its wings,

swallows whole the intricate bone-house.

But whether by the hands of nature or of humanity, in both instances, the speaker admits, “So prone to sadness, this thief—” (45).

The Milk Hours considers grief to be multidimensional in the same way nature and humanity are. There is a constant push and pull between the living and the dead. At the end of the manuscript, nestled between the final poems, are three figures: collages of ferns and flowers, steam engines and ox driven carts. These images serve as moments of rest after emotionally charged ruminations. But they themselves are not absent of emotion. They’re quite eye-catching. Being black and white, the foreground and background blend together; overlaid images become indistinguishable. The ancient ferns, the carts carrying sticks, the modern age; they all become one. These seemingly disparate things become intertwined in our minds. A tree reminds us of a person. A person reminds us of a song. Our own grief reminds us of the rest of our lives.

[1] On Tangibility and Meaning Making: A Review of ‘The Milk Hours’ by John James. Nicholas Molbert. The Adroit Journal. September 6, 2019

[2] Forché, Carolyn. “Blue Hour.” Blue Hour: Poems. HarperCollins. August 24, 2010.