By Accident Here I Am Again: Holly Mitchell's Centos of Matthew Rohrer's The Sky Contains the Plans

Holly Mitchell with Matthew Rohrer

April 5, 2021

Elecment Series #9

*

[pdf-embedder url=”https://fencedigital.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Test-Cento_-The-Sky-Contains-the-Plans-by-Matthew-Rohrer.pdf” title=”Test-Cento_ The Sky Contains the Plans by Matthew Rohrer”]

*

Matthew Rohrer: Also I just read the centos and they’re wild! They feel ~familiar~ but ghostly!

Holly Mitchell: It’s interesting you say ghostly! Rereading The Sky Contains the Plans, some of the lines I used stand out to me now—and echo in my ear—because I’ve spent more time with them. It makes for a whole other way to appreciate the book.

Things I misread also jump out at me now. I see that I added “as” to your line “agreed with me they sang,” accidentally standardizing your syntax. And honestly, I included “the sun is a cruel master” because I believed it was an Emily Dickinson line you’d collaged in. Now I’m embarrassed that’s not the case! I wonder if there’s more I missed.

I read that you embarked on your hypnagogic project of writing lines “between falling asleep and being asleep” in 2010 and took most of the year to write 100 such lines. Then, you went back and responded to some of those lines, finishing the poems later (perhaps much later). Do you think that the timing of your project affected the kind of book it turned out to be?

MR: I do think the way the book was made helped make it different—I actually wrote it very quickly, once I’d gotten the 100 lines. That’s the part that took the longest. After that, it was almost a feverish rush to get to all the lines while I still felt like I was a part of the whole process. I didn’t want to “emerge” from it and start to feel normal again about poems. I wanted to be wholly caught up in the lines, and the kind of power they held over me. I mean, yes, I granted them that power, but it was a fun challenge, and a real spur, to know that the next 100 poems I was going to write were going to be from these lines, and the only way was forwards, basically. I don’t recall exactly how long this process of writing it took, but it was just a few months.

HM: Was it difficult to train yourself to write—legibly—while half-asleep?

MR: I often could not read what I’d written at night, which was sad.

HM: That is sad! Was the title one of your hypnagogic lines?

MR: And the title was actually not a hypnagogic line—originally my title was going to be SEAHORSES ARE AWESOME, which did come to me in the night. But for various reasons I moved on from that as the title. I think we all (me and the people involved in making it a book) decided that it sent the wrong, frivolous message. I am a tiny bit sad about that, because it was one of my most favorite lines to come to me, for obvious reasons.

HM: I liked the seahorses that showed up in one of the poems, but I can see how you’d want something more expansive for the book title. I confess I didn’t actually use any of the hypnagogic lines aside from the title. They seemed off-limits in all caps, serving both as opening lines and titles for the poems. But I think it’s compelling that those “titles” came first when most writers “find” the “right” title after finishing a draft or five. For lines written around sleep, they seem remarkably defined and loud—sometimes fantastic, sometimes mundane but busy like marketing language. In your afterword (“Afterword: All Poetry Is Collaboration” to be precise), you describe these lines as “different voices”. Did it surprise you how different they were?

MR: Yes, definitely, I was surprised by how different these “voices” were. I was surprised by most of them, I think. I certainly would not have consciously chosen to write some of those down. Which I ended up loving, and which I think was a huge part of the energy of the project for me—to start with something so wrong! and how will I go about righting it?

HM: What was it like for you to release this book amid the pandemic? I ask because quarantine affected when I received my review copy as well as where I was (still in my apartment) and what I was thinking about (living in a city with and without people).

MR: In terms of how quarantine affected it, it was sad for me. I had lots of readings planned in several different cities. And I don’t know, in general I think it was harder for people to pay attention to these small books when they came out and there were no readings, no class visits, no personal contact. I am sort of used to flogging my books at readings and colleges. I think the book sort of disappeared. I’m glad you found it.

HM: In the afterword, you also say that you wanted to enjoy writing the poems and that “if we all thought of poems as collaborations with their subjects, we’d be less imperious about them.” Do you think a project makes enjoyment more attainable?

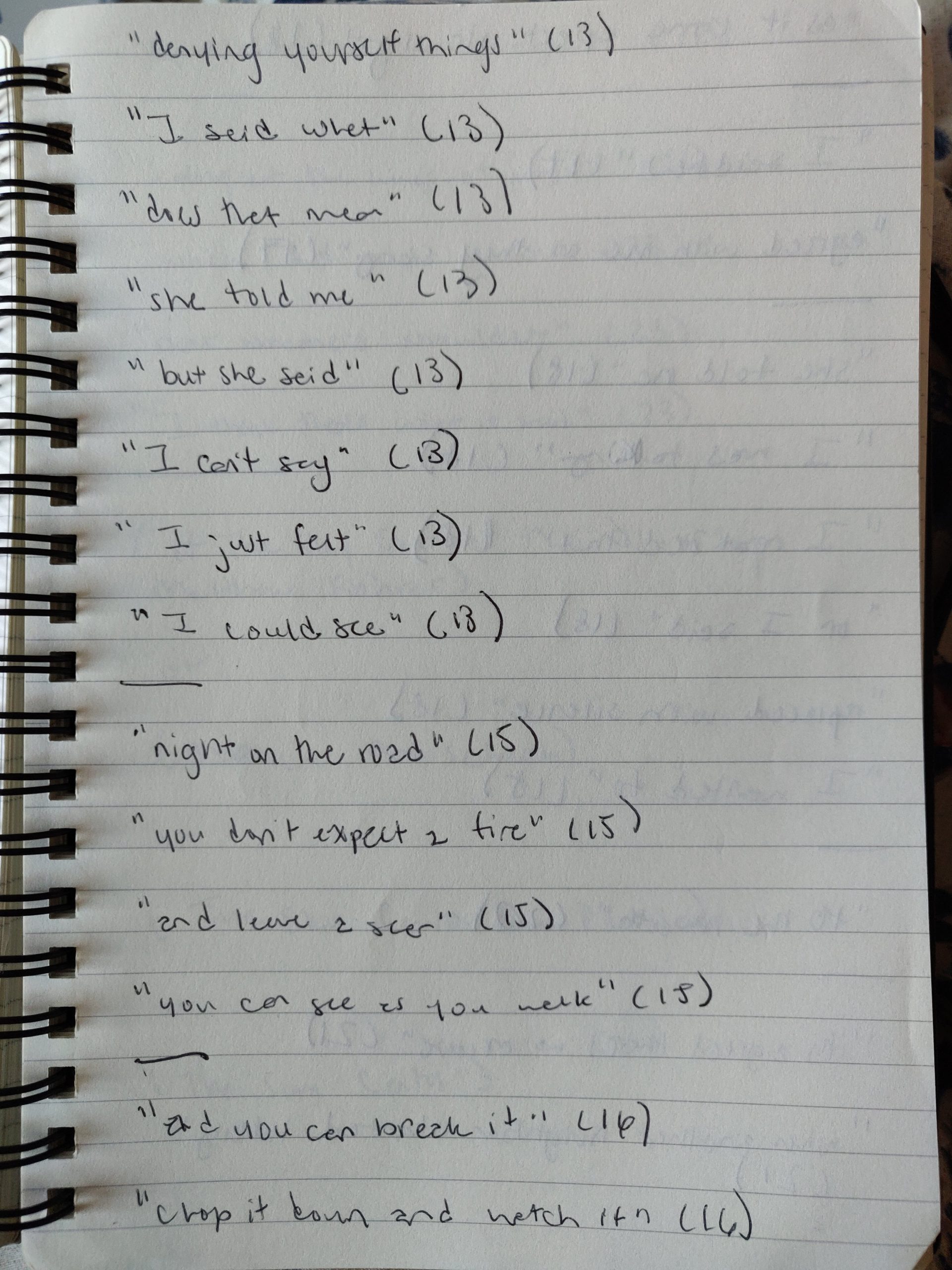

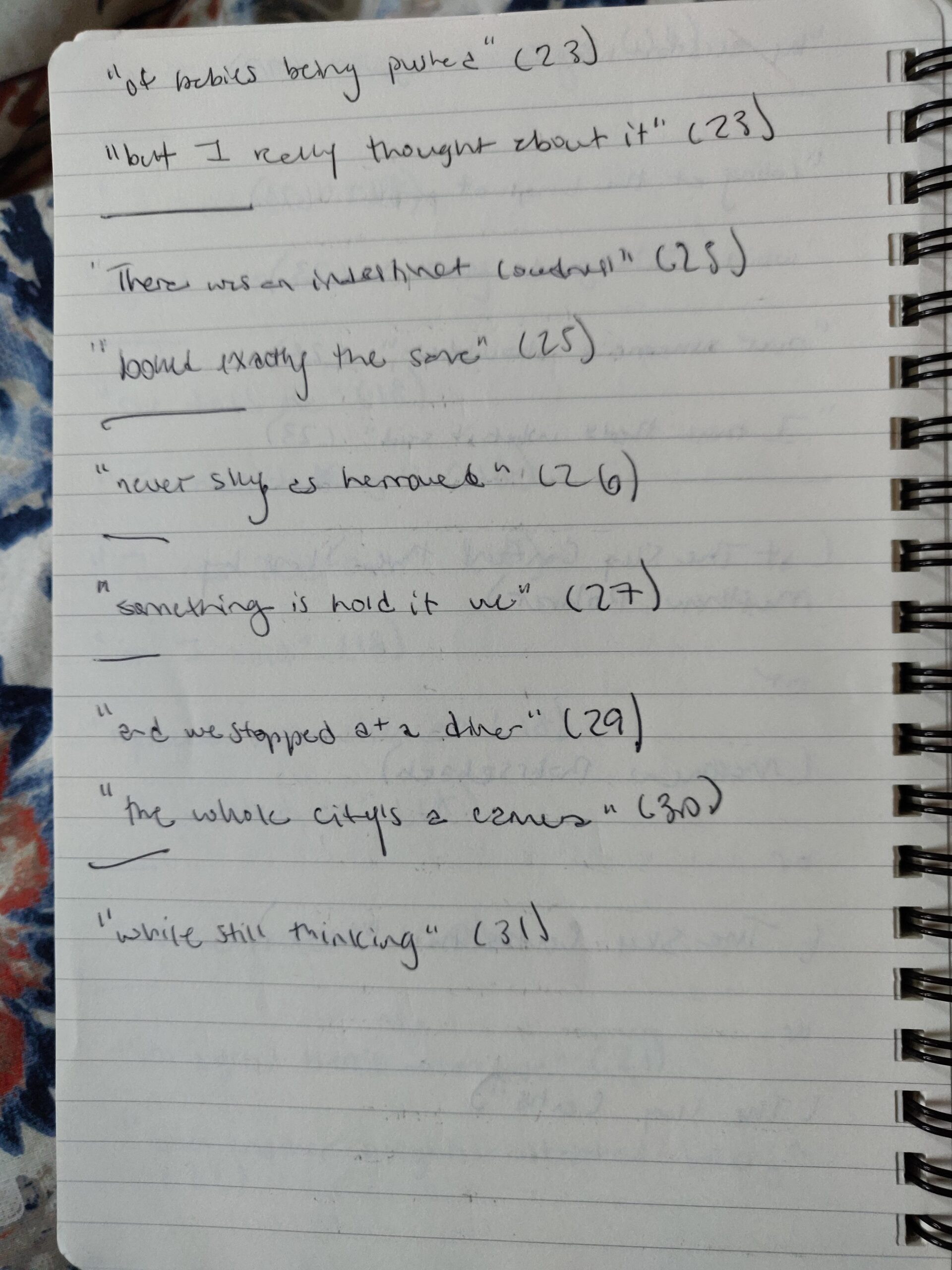

For me, the thing about a cento is that it’s fun to write with reading in the foreground. It’s a poem that can be all listening, all revision—an obvious act of “no creation.” Where the poet can kind of be silent while still making art, which feels indulgent and true to me because I’m so quiet socially. But in a cento, the trade-off for one’s silence is in the transformation—if the line is the same, how is the poem different?—and making the use of another’s work obvious. Together, it’s a performance of not really plagiarizing (Look! How hard! I’m working! Here!), of quotation, of citation, of fair use. Hence the long-ish cento drawn from short poems. Hence the list of page numbers and the cento’s little jokes about the form. (Is it controlling? Fangirlish? What is risk anyway?) If this is a book review, then I hope it’s the sort of review that previews the sensibility of the book.

MR: I think the idea of a cento as a book review is so great! I want to thank you for thinking of doing it that way. And what you said reminds me of something Mary Ruefle said about her erasures—she said something like: doing erasures gives me the pleasure and the feeling of writing poetry without having written any poems. I feel that way about centos and other kinds of collages or found poetry.

I guess I don’t know if a project makes enjoyment more attainable, but it certainly can. I think it just depends on the project. Some people’s projects aren’t very fun. This one was, at least for me. I think if a project makes you write differently, then you’ll attain pleasure. A project that ends up helping you write the way you always write doesn’t seem that cool.

*

*

Holly Mitchell is a poet from Kentucky, now based in New York. A winner of an Amy Award from Poets & Writers and a Gertrude Claytor Prize from the Academy of American Poets, Holly received an MFA in Creative Writing from NYU and a BA in English from Mount Holyoke College. Holly’s poems have been published in many literary journals, including Berkeley Poetry Review, Day One, No Dear, Juked, Paperbag, and The Moth Magazine.

Matthew Rohrer is the author of The Sky Contains the Plans (Wave Books, 2020), The Others (Wave Books, 2017), which was the winner of the 2017 Believer Book Award, Surrounded by Friends (Wave Books, 2015), Destroyer and Preserver (Wave Books, 2011), A Plate of Chicken (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2009), Rise Up (Wave Books, 2007) and A Green Light (Verse Press, 2004), which was shortlisted for the 2005 Griffin Poetry Prize. He is also the author of Satellite (Verse Press, 2001), and co-author, with Joshua Beckman, of Nice Hat. Thanks. (Verse Press, 2002), and the audio CD Adventures While Preaching the Gospel of Beauty. He lives in Brooklyn, New York, and teaches at NYU.