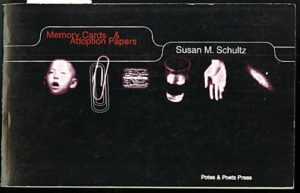

Jordan Davis Reviews Susan M. Schultz's Memory Cards & Adoption Papers

Susan M. Schultz

Potes and Poets Press, 2001

Reviewed by: Jordan Davis

November 14, 2002

// The Constant Critic Archive //

When I worked at the art gallery ten years ago, Ted Greenwald told me a few times to hurry up and get my first book out of the way so I could get down to business. But what about Wallace Stevens? I said. What about him, Ted said.

Some second books are such about-faces from their author’s debuts, mark such a radical shift in perspective on the problems addressed the first time round, you have to speculate what provoked the difference, e.g. Philosophical Investigations, or The New Testament. In the somewhat more parochial world of American poetry, The Tennis Court Oath comes to mind. So does Memory Cards & Adoption Papers. Susan M. Schultz, a professor at the University of Hawai’i-Manoa, is the editor of The Tribe of John: Ashbery and Contemporary Poetry. Her first collection, Aleatory Allegories, derives much of its vocabulary of evasion and abstraction from Ashbery’s middle period, from the cascading narratives of impersonal forces that stud Three Poems through the limpid and remorseful sarcasm of April Galleons. There’s even the hallmark of an Ashbery book: the frequently-pretty, very-long poem of indiscernible subject, in this case a blizzard of serial and subsidiary clauses titled “Holding Patterns”:

So good merely to think through

early morning, birds and helicopters

the music of this hour, a rustling above

me, as hope catches like a gear that isn’t yet stripped, nor bitterness

invoked by slights conceived not as

goads but as wounds to the body politic,

democratic institutions above all prone

to gridlock (not hemlock) like the pages

of a French notebook that organizes

letters as numbers, graphemes lost as

found in this farcical outpost

of the perfect tongue armed against

invasion and experiment. (AA, 72)

This isn’t strict quotation from the Book of John, though. With Chris Stroffolino, Schultz shares an ambition to improve on Ashbery’s resigned goofiness by reaching for Shakespearian effects and scope (in the passage above, by punning glumly, and using comparisons to subjects outside aesthetics, such as civics). The lead-off anthology piece “Mothers and Dinosaurs, Inc.,” insists that “puns do tell / us something” even as it circles its baseball-as-life bases; in these lines:

What

ifs are history’s best stories,

which even those in pin-stripes

knew as they logged in runs and

dodged questions.

Schultz leans so hard on the secondary meanings (Yanks, Dodgers) I almost don’t see the evasive, jogging businessmen intended. Although she uses magisterial connectors, such as “so,” “such,” and “as if,” in most poems in Aleatory Allegories, Schultz does so in a conflict between claiming to understand life i.e. control it, and taking life seriously enough to admit she doesn’t know in advance how it will turn out.

Schultz’s style changes abruptly in Memory Cards & Adoption Papers. For starters, the verse sentences that ran for six or seven roughly octosyllabic lines are now prose phrases. The connectors are gone, changing the tone from skittish irony to something more heat-worn and patient:

My mother lived in North Africa during the War. Loved sunsets. Her amoebic dysentery, suffered for the better (worse) part of a year, paradoxically cured by mineral oil. Recalls a dead body stuffed in the garbage in Algiers. Watches war documentaries to see where she was when. (MCAP, 6)

Gone the asserted connections between abstractions; dizziness is fun for a while, but (pace Emerson) it’s more relaxing for everyone involved if the reader isn’t constantly being told how to understand. Out with over-determined (and avoided) subjects; in with specific characters in uncontrollable situations. Seeya, puns; hello, koans. “A young woman asks: ‘What do you do if there is a tiger outside your cave?’ Lama laughs. Old defenses are like remembered hostels. You must change yourself. Not Rilke, more reasonable.” (MCAP, 19) Eliot said that wit consists of being reasonable in the face of the lyric; this book’s wit tranquilly moves towards its subjects instead of running away from them. The resulting prose poems, with their domestic upheavals and random events, have the emotionally plugged-in, improvisatory feeling of a Mike Leigh movie.

And then the neighbor fell through our ceiling. It went like this. At 10 p.m. on Valentine’s Day we heard a man talking loudly, urgently, as if in the room with us. His wife had left him; he’d gone to a psychiatrist, “done the right thing” but it hadn’t worked; he’d lived on the street; he wasn’t using; he needed to clean out the termites, patch the walls; she’d left him nothing; he couldn’t stand the woman across the parking lot who beat up her child in front of him. Turns out he was by himself in the attic. His voice quieted and we went to sleep. At 1 a.m. the attic stairs screeched. This time there were other people with him: a former boss, a woman who couldn’t speak English, a black man who was chasing him. He stumbled and fell, his foot crashing through the ceiling of my study. “Is everyone all right?” he asked his colleagues. We called the police. The policewoman yelled for him to come down through his own unit. Now there was a SWAT team in the attic with him. We crossed to the other side of the parking lot, still heard him. She yelled again. A crash, shadow in the window. He stumbled out of our front door. Clutched a soft military cap, a toothbrush and a wrapped gift for his wife, who would, he insisted, be coming up the street in her white van at any moment. Taken away for 48-hour evaluation. Came back. Arrested for peeping at a woman breast-feeding her child while he, in women’s clothes, jerked off. His townhouse full of stolen panties. A pizza ad hangs on his doorknob.

2/17/99

Not to give the impression that Schultz is a hard-boiled realist — this is more focused and energetic a narrative than most in Memory Cards. But this poem records a breakthrough for Schultz. The constellating effect that up to this point yields enigmatic bright points suddenly snaps into a previously unknown but recognizable image. That this image elicits empathy, laughter, and anxiety all at once testifies to Schultz’s brilliance. Other writers (Ron Silliman or Barrett Watten, for example) have compiled gritty data into rectangle shapes, but they tend to release the tension in any given moment or case as they aim for a completeness that would indict the darkness. [Or, they’re brilliant too, but the political frame through which they evaluate themselves requires them to stick to the general, to stay on message, when they could be reclaiming the salient anecdote from the forces of Reagan.]

I’ve withheld until now one point. This clear-eyed book, which, like its predecessor, enjoys distorting syntax up to but not passing the point of imparsability, but otherwise differs so sharply, all but explains how the change came about. It has to do with its subject of motherhood: being a daughter, letting go of one’s own mother, being pregnant, miscarrying, aborting, and adopting. “It’s just a picture, Bryant says, not a baby. But it is the form of our baby, his precise measurement on photographic paper, his after-birth mark. I keep my eyes on the web.” (67) The batter’s mantra that Schultz modifies here catches exactly what I value so much in this book. Its motto is “to observe without judgment”; what it implies is that there is something worth attending to.

COMMENTS:

Tom Thompson January 6, 2003 at 4:18 pm

Well, that last paragraph kinda gets popped on you, there, like the end of a mystery novel where it wasn’t the butler did it after all, but Clarice the neighbor (who doesn’t appear in the book until the last page). I read an implicit intra-generational sweep of the paw in the implication that Schultz’ first book was brilliantly pre-occupied with fragmentary pyrotechnics of wit, but that we want that AND more. Is this a statement we can carry to broader regions? Something’s going on in the land Ron Silliman calls “post-avant.” There’s a generation of poets whose first books dazzle in bits and pieces, but recent appearances in journals suggest a horizon newly staked with attachment points, somethings “worth attending to” (in Davis’ smart, clear phrasing). This is the way Ron Silliman thinks another post-avant, Jennifer Moxley, is pointing (he cited her recently on his blog http://ronsilliman.blogspot.com). If you doubt something’s turning, see the freak-out that Silliman’s appreciation of Moxley (and her apparently new-found penchant for straight-talk) caused on the Buffalo Poetics List. I don’t know the link, but you can get the gist at Silliman’s blog. And now, as Rebecca Wolff points out in preface to the most recent Fence, babies are busting out all over: be it with Susan Schultz or countless others coming of age. Nothing disjoints consciousness like a newborn; and nothing makes you so simultaneously long for and realize a joining. A post-lang Po generation that dazzled with syntactical disjunction (yes, beautiful, but…) is coming out with work that attaches at the body familial (see Rachel Zucker’s poems rife with the rips and ties implicit in young parenthood — appearing now from Colorado Review to Pleiades, and forthcoming in book form from Wesleyan). I haven’t read Gabriel Gudding’s book but a look at the review on Constant Critic makes me wonder what next for an auto-arse-admiring poet who has a young child (as Gudding does, I think). Will Gudding’s child demand entry into so frantically self-smart and auto-erotic a poetry? Should s/he? My two young sons are nodding their heads, vigorously; but like I usually do with them, I say, “OK, guys, but gimmee a minute here, I’ve got to think about this.” And while I’m thinking they run out into the street or wherever and the time for thinking is done. So then: a generation so intent on its (our) own navel is now squinching through oomphalos and out the other side? with skills sharpened to a steely new glint by attachment? Or is it merely narcissism + one? I think it’s a different animal than narcissism — very different — but also think it a question worth raising in broader context for this promising generation that includes Schultz and, for that matter, Davis himself…

Ghost of the Not Quite Dead Sorrentino February 4, 2003 at 4:23 am

Since I’m just lurking around reading all of this I’d like to comment not only on ‘the suprise ending’ of the review but on the review of the review by someone allegedly named tom thompson… tom, dear man, friend of language poets everywhere, are you serious? Am I reading People magazine or are we discussing poetry? Having babies isn’t going to make anyone a better, more socially responsible person, and it certainly won’t advance anyone as a poet (except, perhaps, at dinner parties). This is an offensively bourgeoisie idea if there ever was one.

POETRY, THE APOGEE OF THE ARTS

TESTIFY!

tom thompson February 10, 2003 at 10:49 am

To my dear not quite dead yet Sorrentino Ghost:

Ole!

Over-ebullient, perhaps. Myopic, indeed. “Offensively bourgeois”? OK. There are lots of ways one gets attached to the world; this is obvious. That a young parent emerges from the nursery with babies in his eyes–babies, babies, everywhere he looks!–is not I think something that would worry Marx too much.

An amendment:

“And a keelson of the creation is love.” So testifies Whitman. Better, hm? Why yes.

Biographically yours,

the alleged