A Memoir of Editing Diane di Prima’s Revolutionary Letters

Garrett Caples

October 16, 2021

Elecment Series #12

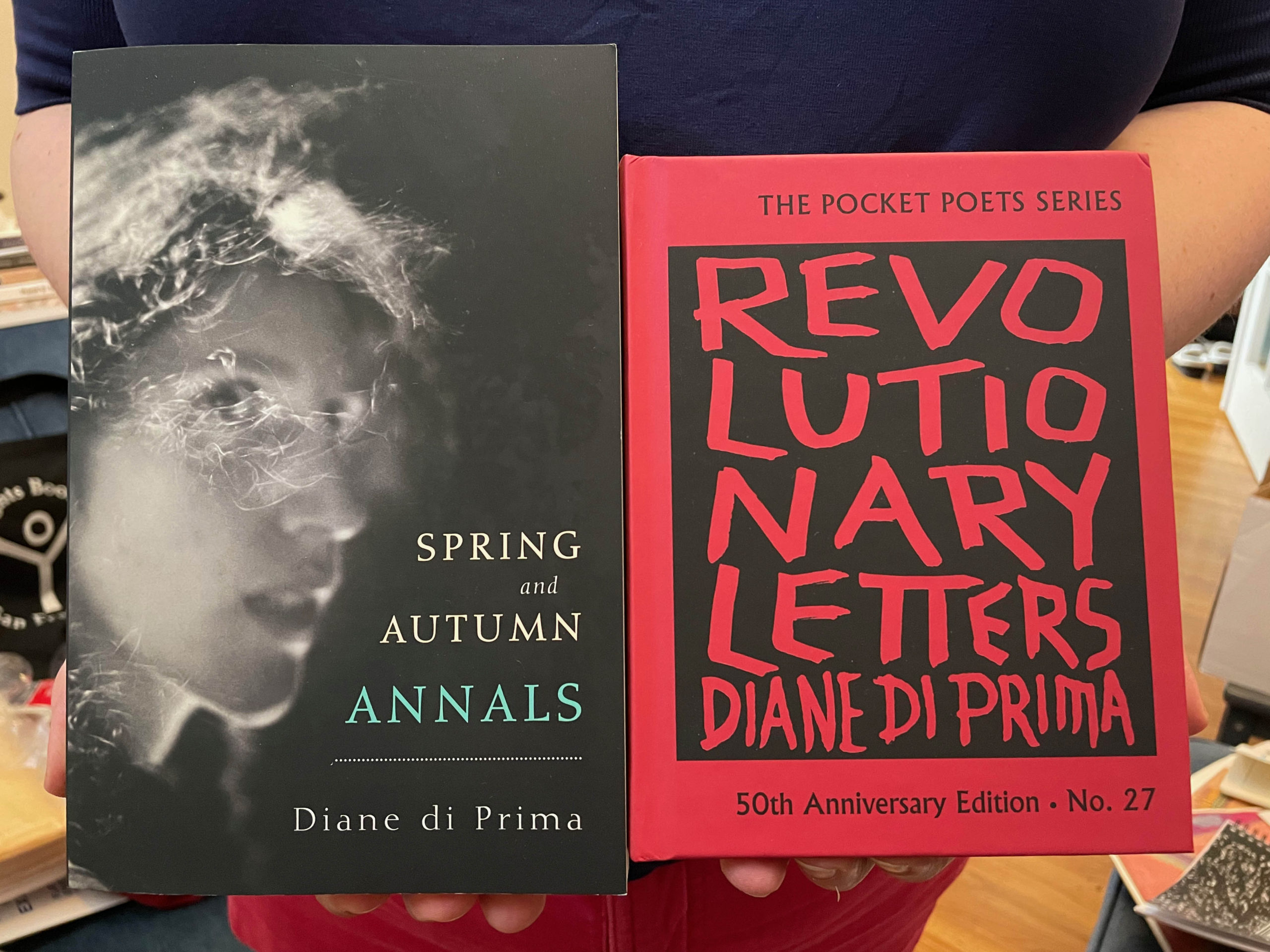

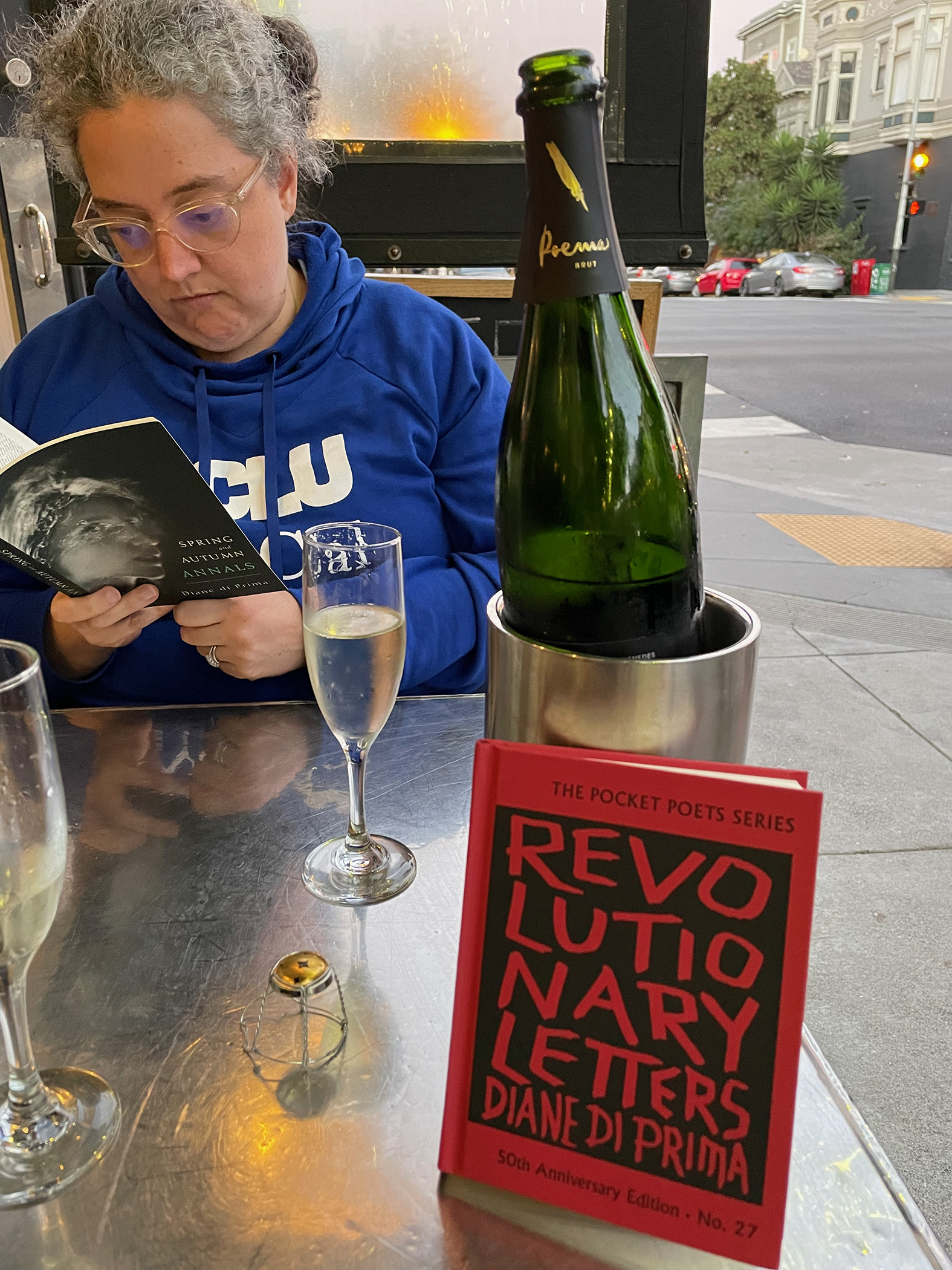

cover photo by Sheppard Powell for The Poetry Deal (2014); covers of Spring and Autumn Annals and Revolutionary Letters

———————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

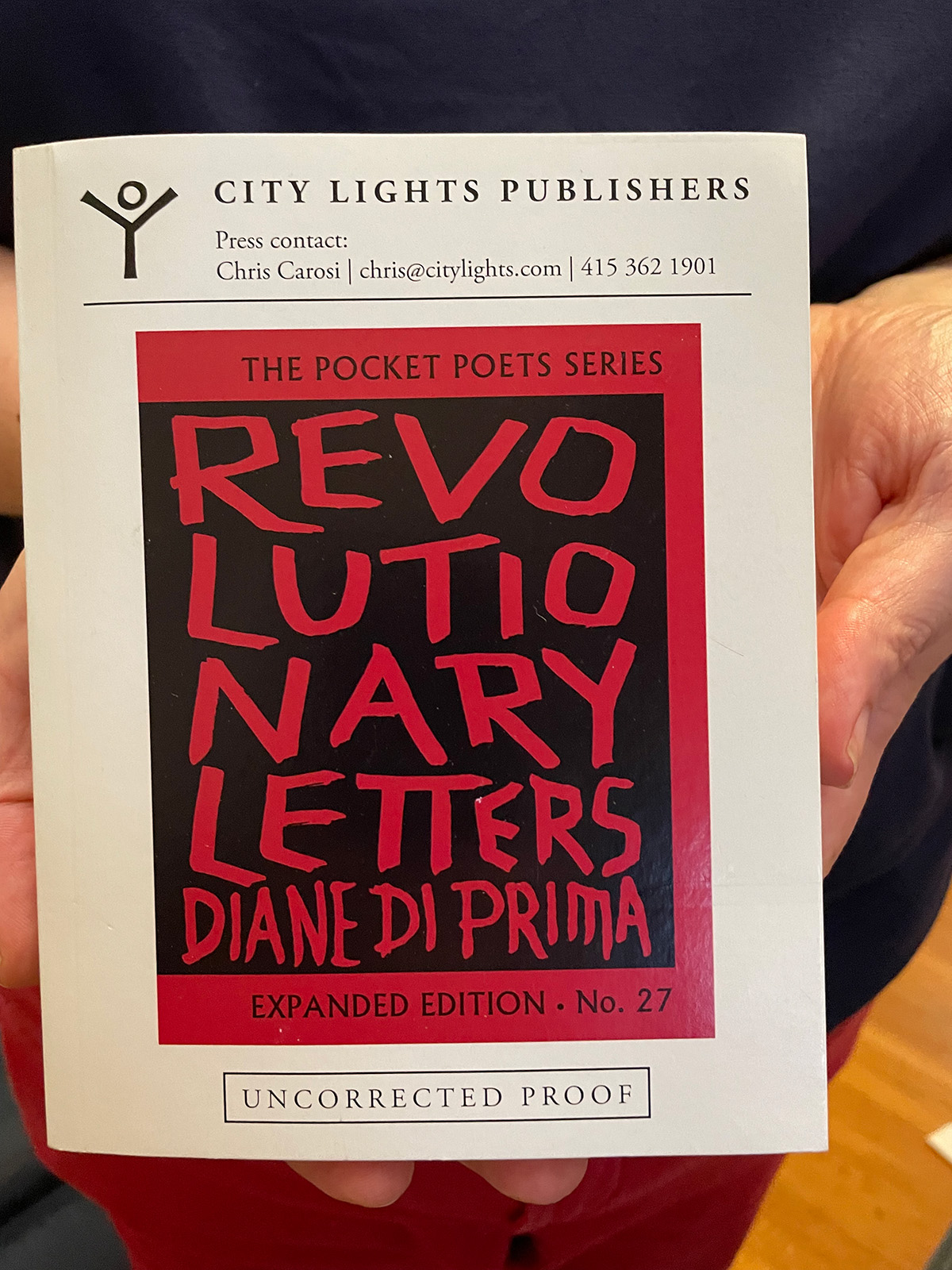

In October of this year, City Lights published the 50th anniversary edition of Diane di Prima’s book of poems Revolutionary Letters (1971–2021). The gravity of the task of editing this volume for the press has weighed on me, because it’s an important book. There are books, of course, I think are important and the world doesn’t agree, or only a small minority does, but most serious students of 20th century American poetry, as well as the legions of readers Revolutionary Letters has inspired over the past half-century, would be compelled to agree it’s an important book, a classic. So it’s a big responsibility, especially after the author’s death, which thrusts all potential blame onto the editor, who’s been robbed of the one available shield against accusations of incorrectness: don’t blame me, that’s how she wants it.

I approached the task of editing Revolutionary Letters with the mindset that it might be 100 years or more before these poems are ever typeset again. I don’t think this will be the case, but at the same time, being in the business of making books and having some familiarity with literature as a historically determined phenomenon, I know it very well could be. Most individual volumes of verse aren’t afforded the luxury of a 50th anniversary edition, and its acknowledged importance only increases the likelihood that Revolutionary Letters will be revisited sooner rather than later. But books have funny lives: cultural appetites shift; reputations rise and fall; technology changes, so we’re in habit now of sucking text from one edition and spitting it into another, rather than starting anew. Any errors introduced now, especially into the newly added poems, will likely be perpetuated, even if the book is reset. I have to assume this is the one chance to get it right.

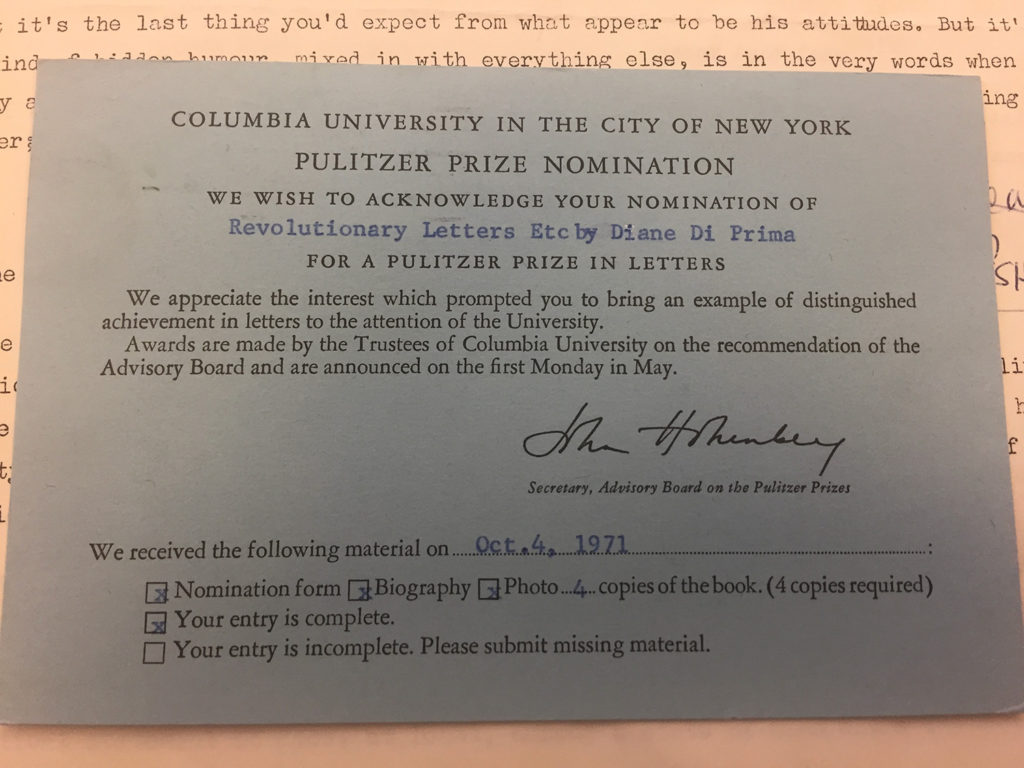

Pulitzer Prize nomination for Revolutionary Letters (City Lights Archive, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley)

*

Having written the above, I’ve just learned City Lights has sold the UK rights to Revolutionary Letters to London feminist indie Silver Press, and the edition will be printed from our InDesign file. This version is already perpetuating itself, even as it will inevitably be altered due to the change in trim size.

Having worked on this book so long (on and off over the course of four or more years), suddenly I’m afraid to sign off on the proofs. Afraid to finally say: it’s done.

*

The fear of signing off: long ago, possibly as far back as 2018, I gave Diane a typeset proof of Revolutionary Letters with the understanding that she would mark it up and give it back, so we could enter the changes and publish the book. We wanted to publish the new edition of Revolutionary Letters simultaneously with the previously unpublished Spring and Autumn Annals, a memoir written in the wake of her friend Freddie Herko’s 1964 death. But Diane was in the hospital after a fall, and she never really left that hospital, though she was eventually moved from rehab to a longer-term care wing. As 2018 became 2019, no proofs were forthcoming; the book was announced, delayed, then canceled, though people have never stopped inquiring about it.

And yet throughout that entire time she maintained she was working on the proofs! I figured one of two things was going on. Either she didn’t have the strength to finish going over the typescript and didn’t want to admit this, or she was deliberately withholding it, because consciously or unconsciously she feared once she let it go she’d die. I leaned heavily toward the latter option, and I wasn’t the only person who thought this. But I didn’t know for sure; it was hard to get a straight answer from her to a direct question, and I wasn’t about to ask that directly. And while I realized she was an 85-year-old in rough shape, the times I did see her in the hospital, she looked quite capable—with assistance, which she had—of finishing a set of proofs. There was a lot of life there till the end.

But the end did come, in October 2020, after the COVID-19 pandemic had rendered her more or less inaccessible for over half a year. Believe it or not, however, she took up texting late in life, and we did exchange a handful of texts. We were in touch after Michael McClure died that May; I told her I was editing his last book, Mule Kick Blues, and she asked to see it, so I printed and mailed her a manuscript. The next I heard she was starting to fail, then the next I heard she had died. Of course, Revolutionary Letters had only been canceled “officially”; if you assign an ISBN number and don’t use it soon enough, it spoils for nebulous business reasons, so we had no choice but to cancel that edition. But there was a tacit understanding that we would still do the book after her death, an event she alluded to in an “after-I’m-gone-you’ll-do-what-you-want” sort of way, and we were able to quickly put everything in motion to re-announce the project and Spring and Autumn Annals for the upcoming season.

You’ll imagine my mixture of emotions when, at the beginning of this final round of production, I received from her co-executor Ammiel Alcalay a fully marked up set of proofs. She had, as I suspected, finished, but not handed them over. As with most of my dealings with Diane, I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. We’d initiated the whole two-books-at-once project at City Lights because we wanted her to have at least one last hurrah while she was still alive. And yet, if I knew anything about Diane, it was she did what she wanted to do, and if she’d finished the proofs and not turned them over, it was a deliberate decision. Maybe she didn’t want the renewed attention; she was clearly weary of the steady stream of requests for interviews and other things demanded of a famous poet. She might have been happier knowing the book was in the works but not having to be there for it. But I really have no idea.

*

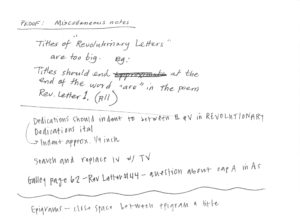

general instructions by Diane; click to enlarge

Today (7/26/21), the book has gone to the printer. The finality of the decision haunts me, though I suppose it will turn into relief soon enough. Sending a book off is usually a joyous occasion, but with this project all I feel is a vague disquiet, even though I know I’ve poured over it far longer and more thoroughly than any book I’ve ever taken through the full editorial process. And too, I had a lot of help, from Diane herself. The proof markup was the most meticulous I’ve ever received from an author, as well as the most knowledgeable, for she had printed and published plenty herself with her own imprint, Poets Press, and her seminal mimeo mag, Floating Bear. I would describe her sensibility as hot type, accustomed to a more mechanical process, and highly resistant to the grid that modern trade press typography tends to impose on books. (If Diane wanted, say, a short poem set in the middle of the page, fuck InDesign, she was going to have it.) But however old school, her sense of layout was highly rational and consistent, and her markup imposed instant clarity on what had been sometimes blurry distinctions between subtitles and dedications, as well as indicating how to rebreak or run over lines when they didn’t fit the Pocket Poets trim size (4.75” x 6.25”).

This was the essence of the editorial task, for Revolutionary Letters had always been an ongoing, expanding project, originally in pamphlet or mimeo form, before City Lights did the first Pocket Poets edition in March 1971. This first edition has 43 numbered revolutionary letters, plus the unnumbered opening poem, “April Fool Birthday Poem for Grandpa,” and a group of unnumbered poems at the end: “Goodbye Nkrumah”; “To the Unnamed Buddhist Nun, Who Burned Herself to Death on the Night of June 3, 1966”; “Rant, from a Cool Place”; the five-part “New Mexico Poem”; the five-part “‘Free City’ Poems,” consisting of “April 24, 1968: For John,” “A Spell for Felicia, That She Come Away,” “Dee’s Song,” “Confucius Was an Old Fart,” and the four-part sequence “Route 101”; and a final four-part sequence, “Canticle of St. Joan,” dedicated to Robert Duncan. Even that edition, however, was immediately supplanted in October of the same year by a second edition adding six more letters.

The third edition in 1974 added another 15, bringing the numbered poems up to 64, while the fourth in 1979 brought the numbered poems up to 70. I’m not sure how long this book stayed in print; Ralph T. Cook’s City Lights Books: A Descriptive Bibliography lists 3,000 copies for each edition, with no reprints, but the fourth edition is so frequently dated in second-hand listings as 1981 that I can’t help but assume it was reprinted at least once. According the scant correspondence in the City Lights archive at UC Berkeley’s Bancroft library, the book was still in print in 1987, but by 1990 it was presumably out of print, as a letter dated December 3 of that year confirms the rights had reverted back to Diane. The next edition wouldn’t come out until 2007, and not on City Lights but rather on Last Gasp, and while the trim size remained compact (5.5” x 7.25”), it was still considerably larger than that of the Pocket Poets. There are 93 numbered letters in the 2007 version, and the biggest challenge had been to fit those 23 Last Gasp-only poems into the Pocket Poets format, along with the 18 subsequent poems Diane had earmarked for the 50th anniversary edition.

size differential between Last Gasp edition and final City Lights edition

(As an aside, I should note that the Last Gasp edition also dropped poems, specifically four of the five “‘Free City’ Poems,” retaining only “Dee’s Song.” I did think to ask her why she excised those poems but never had the chance; she only had the energy to discuss a limited number of things per visit, so I had to pick my inquiries well, and there was always something more pressing to address. I would have liked to have included them in an appendix at the back, but I’m almost certain she would have said no. That would have been treating the book like a historical document rather than a living project, which it essentially remained until her death.)

“Free City” Poems, 4th edition; poems copyright © 1971, 2021 by the Estate of Diane di Prima; click on the images to enlarge and read the poems

When we were prepping the bound galleys of what was then labeled Revolutionary Letters: Expanded Edition for release in Spring 2019, Diane was too ill to participate, but the book had been scheduled, so I had to forge ahead without her. I was able to follow the fourth edition from the opener through letter 70 and then for the final group of unnumbered poems, but in between I was flying blind for a good 41 poems. And this was nerve-wracking because some lines had to break differently from the Last Gasp edition due to the reduction in trim size. I figured I’d sort this out with Diane between the galleys and the actual book, so somewhere out there—collectors note!—unless reviewers tossed them are 40 bound copies of this ersatz Expanded Edition. The proofs I gave Diane to correct were identical to these galleys, right down to the last-minute error of the font dropping a point-size. I quickly realized this and gave her an updated set, but I was not especially surprised to note she marked the earlier one. Despite my fears, however, it had little impact on my ability to translate her edits into the final version. Her markup, moreover, was global, not confined to the poems added after the fourth edition, but rather throughout the book. Not that she revised the poetry itself, but she modernized some punctuation, very minor detail work that won’t be noticed by most readers, but serves the poems well. Stuff like removing the apostrophe before the “s” in references to decades, like “the 1970’s,” which used to be standard but now is considered incorrect.

so-called Expanded Edition galley (2019)

Her biggest innovation in the final edition was changing most of the all caps passages to small caps, which, truth be told, may have saved the whole layout. This one change resolved many difficult points throughout the book. Intriguingly, she left the one all caps poem, #38—about one of the University of California’s several attempts to evict the residents of the homeless/anarchist campout known as People’s Park in Berkeley, CA—in full capitals, a scream of outrage, but otherwise she may have gone a little overboard small capping; as she went along, almost every all caps word, acronym, or even initialism became designated for this treatment, though there were some she skipped earlier on, as if the decision gradually took hold of her. I spent much time trying to determine which examples of all caps were overlooked and which were deliberately skipped. “AIDS,” for example, an epidemiological crisis about which she cared passionately, always appeared in full caps, as did “USA,” and in consultation with her executors, I left these alone. There are other, individual exceptions to the change to small caps, but I can assure readers that every one of these that Diane hadn’t designated herself was fully considered. The newly added letter #105 (subtitled “FIRE SALE—EVERYTHING MUST GO!”) contains some all caps words that, as an editor under the circumstances, I thought should be corrected, but her husband and co-executor Sheppard Powell insisted these were deliberate, and since it’s her right as a poet to have the poem as she wanted it, I left them alone.

extra spaces added to “Canticle of St. Joan”; click to enlarge and read

There are plenty of other idiosyncrasies throughout Revolutionary Letters. She added some seemingly random extra spaces within the closing poem—“Canticle of St. Joan,” a poem untouched in 50 years—for what Shep insisted were esoteric numerological reasons. I can’t argue with that! For my part, I just tried to follow her own tendencies in her markup when it came to ambiguous cases. My biggest intervention: noting that she’d addressed the previously inconsistent treatment of publication titles by italicizing them throughout, I realized that she’d overlooked one in “Revolutionary Letter #6”:

avoid the folk

who find Bonnie and Clyde too violent

who see the blood but not the energy form

This is clearly a reference to Arthur Penn’s film Bonnie and Clyde (1967), still in the theatres in 1968 when she began writing Revolutionary Letters and controversial for its depiction of violence, but the phrase hadn’t been marked for italics. While I hesitated to alter a poem that had appeared this way for over 50 years, Diane had no such scruples modifying the earlier poems in the book, so following her example and consulting her estate, I made the change. Such minutiae will surely fade from my consciousness in due course, but I note this as an example of the detail work that went into the present edition, for the benefit of future editors and typesetters at the very least. I won’t say the book is perfect—what book is, really?—but I will say it reflects Diane’s intentions, as well as her sense of the book as a living document, as much as humanly possible.

*

Diane was full of surprises, even in death. In the preceding section, I wrote we added 18 new letters to the poems in the Last Gasp edition, which was true in terms of the proofs I gave her to correct. In that version, the Expanded Edition galley, the numbered “Revolutionary Letter” sequence ends at #111, a poem subtitled “ANTHEM” and dedicated to Bruce Conner. She also noted on the proofs that she wanted this to be the very last poem, but it wasn’t clear whether she’d considered the unnumbered poems that follow the sequence and have always ended the book. At length, we decided to leave those poems at the very end and interpret Diane’s instruction to mean the last poem in the numbered sequence.

You’ll note, however, that “ANTHEM” is now #114 in the 50th anniversary edition, meaning three more “Revolutionary Letters” surfaced after her markup. One of these poems, now labeled #111 (subtitled “DON’T TURN AWAY”), is seemingly older than the other two, something Diane had written sometime after the 2007 edition, but hadn’t come across yet when she gave me the new poems to add. Numbers 112 and 113, however, were of more recent vintage, typed up for her by Cedar Sigo during a 2019 visit. The first, #112, is, of all things, a seven-line shoutout to the rock band Queen for “show[ing] us how” to endure “While the ground under your feet is burning”. Though unmentioned as such, Freddie Mercury’s death is probably a subtext here, given Diane’s aforementioned activism around the AIDS epidemic. (I’ve heard a whole manuscript of her poems on this topic exists, though I’ve never seen it.) The second, #113, is a five-line “Dream About Christchurch,” concerning the New Zealand mosque shooting on March 15th of that year. I don’t know whether letters #112 and #113 are the last poems she ever wrote, but they are certainly the last two written for Revolutionary Letters. If their relative spareness reveals her fading energies, however, they also show her continued engagement with the revolutionary concerns expressed throughout the book, while her stipulation of the older “ANTHEM” as the final “Revolutionary Letter” allows the series to end with a piece written while she was still in full command of her powers.

*

Around 1 a.m. one morning after working on the book (3/17/21, according to my Notes app), as I was falling asleep, I fired up my phone and typed the first 12 lines of the following poem; I wrote the next 21 lines and did the layout the following night on my laptop. I dicked around with a thousand titles, only settling on one weeks later, when it was being printed as a broadside.

#115 AND COUNTING

A REVOLUTIONARY LETTER

for Diane di Prima

once again it is i

who am the most high

running off halfcocked

like a rotisserie special

two sides from the menu

corporate capitalism

corporate fascism

inevitable collard greens

pull your camel

through the needle

see where it leaves you

pose with award you denounce

see what it amounts to

a hill of pinto beans

means to embittered ends

that lend themselves to sale

dirty fucks! but who am i

that guy from the first line

to opine on the lie

of united states

the hell we decline

but still have to do

a version of (aversion to)

a revolution Not

Fucking

Likely to occur

covid’s proven doom

will assume the form

of supply chain failure

face it the state’ll

dissolve before it’ll

solve your problems

it is your problem

I admit I was quite taken with this poem; it felt like the first good poem I’d written in the year since I finished my last book. That book, Lovers of Today, appeared from Wave on October 5, coincidentally the same day as the publication of Revolutionary Letters, and I liked this poem because it was nothing like Lovers of Today. My poems are nothing like Diane’s but I could feel her influence seeping in nonetheless; inhabiting Revolutionary Letters for so long made me feel like I wasn’t explicit enough about the need to dissolve the corporatized and militarized state we live in, though I consider that a given of any poetic practice that intersects, as mine does, with surrealism. But Diane in Revolutionary Letters is usually at her most poetic when most plainspoken, which to me as a practitioner has always seemed like the most difficult thing to achieve. I’m not saying I achieve it here—the poem was form-driven in the sense it was generated by sound, as a series of off-rhymes—but the last seven or so lines are in that direction, where the form and the thought are locked together, and the poetry emerges from that lock.

The layout of this poem has little to do with Revolutionary Letters, and is more involved with my own struggle against the left-justified margin. I seldom stray from it because I usually feel like I’m wasting time, diverting my attention from the line itself to its appearance on the page; layout, for me, distracts from generation. But while it doesn’t resemble any of Diane’s letters, the layout is influenced by them on the line-to-line level. The title, subtitle, and dedication are all laid out according to Diane’s scheme for Revolutionary Letters, and while I would not presume to write “Revolutionary Letter #115” as though to continue the series, I wanted the title to suggest the “Revolutionary Letter” is a form anyone can take up, the form itself being the potentially infinite and collective hundred fifteenth “Revolutionary Letter.”

I write that in all earnestness, because I feel no ownership in relation to Diane’s work in the slightest. I never sought her out, but, as has happened to me more than once editing books for City Lights, I was thrust before her greatness, and it affected me as a poet, because the lines dividing my poetry from the rest of my literary activities don’t really exist.

*

Fun facts about the book:

1) After Diane’s death, her executors told me she didn’t like the font we’d used, claiming it was “too fancy,” and asked if we could change it. No! If we changed the font at that point, we would’ve had to start all over, because, in order to fit everything into the Pocket Poets trim size, we’d had to cheat the grid at every turn, encroaching on margins and gutters, tweaking the kerning, the whole nine, and different fonts never line up exactly, even in the same point-size. The poems are set in Garamond, which is about the most ordinary font you could set a book of poems in; it wasn’t fancy at all! After some discussion, it emerged that what Diane really hated about Garamond was the ampersand; it looked, she had said, like a fat man pushing a lawnmower. This was too amazing not to indulge, so after some rooting around, our designer Gerilyn Attebery gave me half-a-dozen ampersands to show her executors, and they picked the one in Miller regular. So this might be the only book set in Garamond with Miller ampersands.

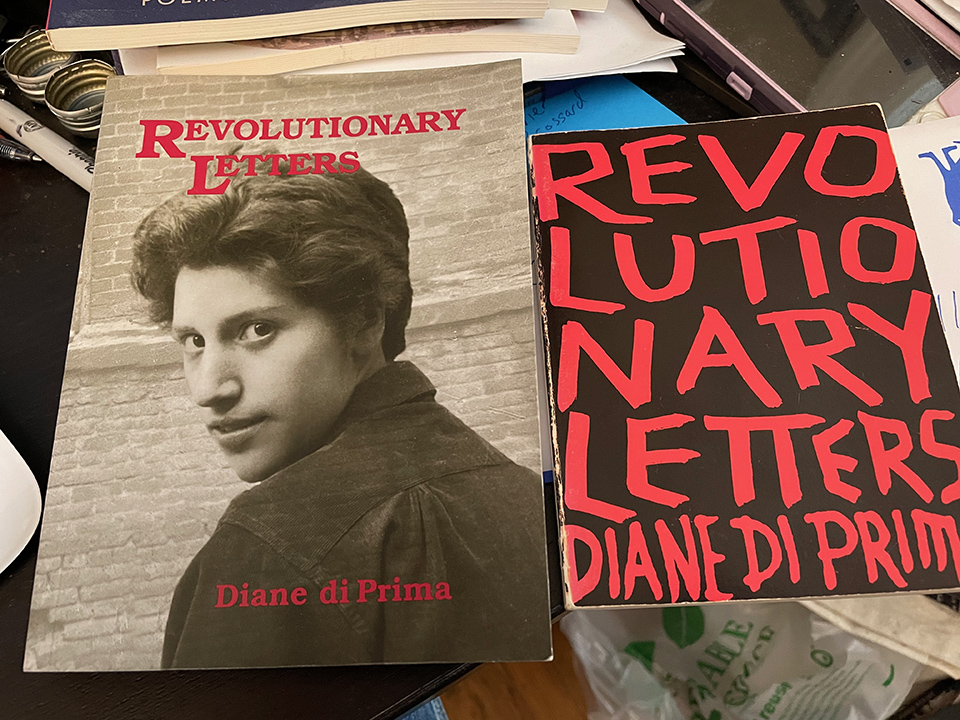

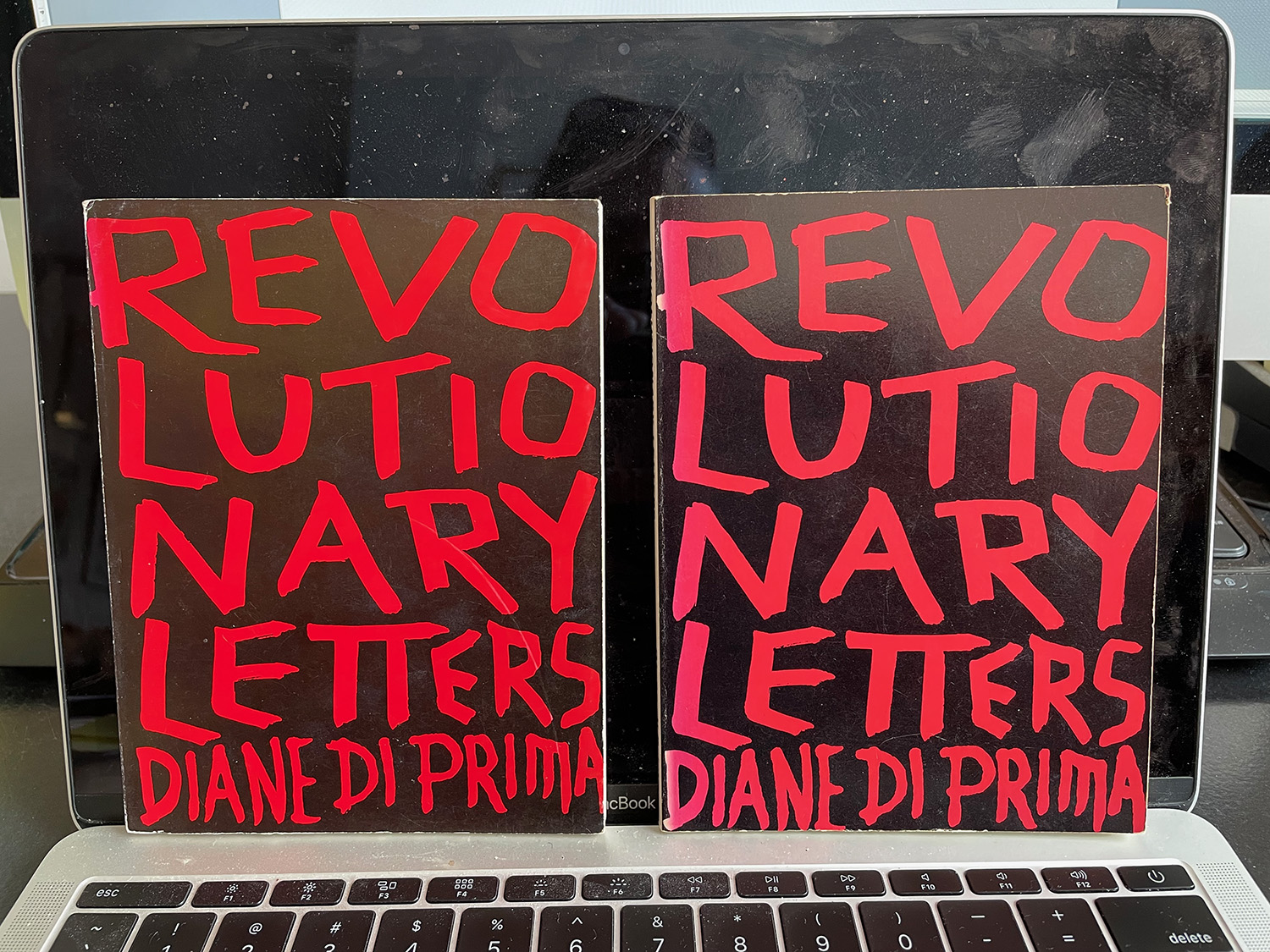

2) The cover of the previous City Lights editions of Revolutionary Letters was a black rectangle entirely filled by the title and Diane’s name painted in red, in the distinctive calligraphic hand of Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Last Gasp had used a vintage photo of Diane on its cover but naturally we wanted to return to the book’s classic look. During our initial attempt to republish Revolutionary Letters, however, City Lights’ executive director, Elaine Katzenberger, asked if we—“we” at the time being me and the previous City Lights designer, Linda Ronan, for this project went on long enough for staff turnover!—Elaine asked if we could come up with some visual way to distinguish this edition from the previous ones. Unlike previous 50th anniversary Pocket Poets City Lights has done—Kaddish, let’s say, or Lunch Poems—Revolutionary Letters eschews the iconic original series design of a rectangle housing title and author surrounded on three sides by a black or colored border with the series name and volume number. Lawrence’s lettering goes all the way to the edge, so there’s literally no room for any print or device signifying the new edition. I suggested reversing the colors, black letters on red; it looked like shit! The letters lost the vibrant, almost psychedelic quality that Lawrence managed to achieve with the potentially austere red and black anarchist aesthetic. Finally, I realized the original cover itself could be that title/author rectangle within the three-sided border of the iconic Pocket Poets design, with volume number, series name, and anniversary noted. Does it lose some of the power of the original cover? Sure. But the fascinating thing to me was that it worked, effortlessly; visually it juxtaposes two very different sides of Lawrence’s design aesthetic, yet instead of clashing, they blend seamlessly, as if the cover was always thus. It has the hallmark of the awesome minimalism of the Pocket Poets design, either black & white or just two colors playing off each other visually even as they accomplish all the practical signifying work of typography.

first (1971) and fourth (1979) editions of Revolutionary Letters

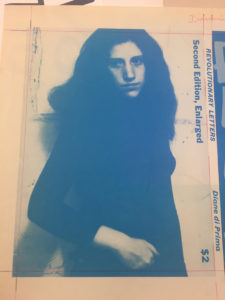

To my frequent regret, Lawrence Ferlinghetti didn’t systematically keep copies of all the City Lights publications or original cover art. At the office, we only have copies of the first and fourth editions of Revolutionary Letters, and if his cover painting still exists, I don’t know its whereabouts. I looked at Diane’s file in the City Lights archive at the Bancroft Library in Berkeley and all I found was an old blueline proof of the second edition back cover, nothing we would use nowadays, hence its relegation to the archive. I noticed, however, when we hit on our cover solution, that the lettering doesn’t fully fit on the book; some of the right-hand edges get cut off, so it would have been useful to see the original. But what saved the idea was the very analog quality of the older printing process, because on close inspection the covers of the first and fourth editions aren’t exactly the same. The lettering is differently situated on the rectangle for each edition, enough that different edges get cut off. I daresay the letters on the fourth edition might be almost imperceptibly larger but they are definitely lower. Scanning both covers allowed us to capture each letter uncut, and the lettering as a whole appears in a way it had appeared before, assuming a vaguely hyperbolic curve on the sides.

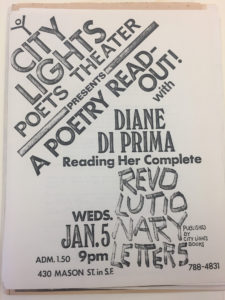

blueline of second ed. back cover, 1971; flyer for reading, date unknown (City Lights Archive, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley)

*

At some point while we were working on the 2019 Expanded Edition, imagining, no doubt, giving a reading from the book, Diane asked for an index of titles and first lines. Given that almost all of the poems are titled “Revolutionary Letter” plus the number, finding a particular poem among the letters would have been a challenge on the fly. In truth, the index I prepared was mostly an index of subtitles and first lines, along with the handful of individual titles from the opening poem and the ending poems. But as I indicated earlier, the distinction between subtitle and dedication was not always clear prior to her markup. Once I received this I had to take out any dedications I’d accidentally included and put in things I hadn’t realized were subtitles. And following the consistent scheme that her markup imposed, I had to change all the indexed subtitles to small caps to match.

Yet far from being the colossal pain in the ass that, on some level, it also was, retooling the index turned out to be one of the more pleasurable tasks of the whole process of making the book. It was reinhabiting the book, in an almost cubist manner, and as I reworked the listings and corrected other mistakes, new little stanzas seemed to glint out at me from the page, while the random nature of the work—you might have to work on the B listings, but then jump to the Ts to address the next issue—turned the book into a fully non-linear text, where you could juxtapose unrelated parts and produce a new relation.

All of this put me in mind of my one friend who used to make his living as indexer, Andrew Joron. Andrew’s book The Absolute Letter (Flood, 2017) contains a poem he wrote while indexing Robert Duncan’s The H.D. Book (California, 2011), called “Back Of.” He’d noticed Duncan’s frequent resort to this old-fashioned locution, and began keeping an index of them as he went along, despite it’s having no purpose for the index he was being paid to compile. Then he selected ones from this set and arranged them into “Back Of,” or what he subtitled “a sampling of ‘back-of’ constructions from Robert Duncan’s The H.D. Book.” Without Andrew’s example, collaging from a heavy hitter like Duncan, I doubt I would have had the nerve to write:

Index to Revolutionary Letters

bald eagle

be careful

beware of those

on the way home

can you

avoid the folk

advocating

ancient history

who is the we, who is

all thru amerika

it is the establishment—that 1%

as soon as we submit

my body a weapon as yours is

out of the heaps of the bodies of suicides

one thing they never mention in western movies

have you thought about the american aborigines

how did we come here? my bones

remember sacco & vanzetti

if the power of the word is anything, america

it’s terrorism, isn’t it, when you’re afraid to answer the door

fire sale—everything must go

from san francisco

the vortex of creation is the vortex of destruction

and it seems to me the struggle has to be waged

over & over we look for

poem at dawn

these are transitional years and the dues

they’re us

are you prepared

now let me tell you

o my brothers

reality is no obstacle

think of it as an experiment

how much

even an hour of this

experiment

drove across

empire

in the wink of an eye

it is happening even as you read this page

take a good look

the center of my heart is arab song

the east edge is

cacophony of small birds at dawn

it is in god’s hands. how can I decide

it takes courage to say no

and as you learn the magic, learn to believe it

a lack of faith is simply a lack of courage

don’t give up the eleven o’clock news for

awkward song on the eve of war

we are in the middle of a bloody, heartrending revolution

not western civilization, but civilization itself

i have just realized that the stakes are myself

i guess it must be up to me

i will not rest

i vanish

velvet lady, lay on velvet pillows

let’s stop for a moment to remember

some of us have to mourn

someone

I’m not going to lie; writing this poem was a gas. It was like getting to do a five-minute remix/edit of the dopest LP of source material. Obviously, Diane had done the heavy lifting, and all I did was capture a poem emerging of its own accord. And yet, insofar as I was still writing I felt like I was writing about the present. Four years under Trump, climaxing with the pandemic, the period during which we prepared Revolutionary Letters coincided with a time of violence and chaos unprecedented in my lifetime, but Diane’s project, originating during the worldwide upheaval of 1968, had forged a political lyricism that still feels commensurate with our political situation. I’m not saying nothing in the book seems dated but that by and large the issues Diane addresses as most urgent—everything from ecological collapse to water rights to violence against women to racism to the capitalist state itself—are the most urgent ones of today.

Near the end of working on the book, I had to look at some of Ted Berrigan’s prose for a different project and came across a trio of early ’70s book reviews he wrote where each review is a poem collaged from lines from the book at hand. If I had Berrigan’s nerve, insofar as this is a book review, I’d have made “Index to Revolutionary Letters” the whole thing!

*

And then, I have to wonder, was all this for naught? Will posterity one day set my efforts aside and return to the original 1971 edition of Revolutionary Letters? It’s not out of the question. I’m no expert on Whitman, but my impression is that posterity prefers the 12-poem 1855 Leaves of Grass over the roughly 400-poem 1892 “deathbed edition.” The evolution of Revolutionary Letters isn’t nearly so extreme, growing from 43 to 114 letters, plus the unnumbered poems, though the 50-year interval between the first and the final edition is longer than the 37 years Whitman spent adding to his book. But there’s an undeniable power and unity to the first 43 letters—or let’s say 49, given how quickly the next six poems were added—that grows more diffuse as the project goes on. The first two (or even three) editions of Revolutionary Letters were published at a time when genuine revolution in the U.S. still seemed possible, hence Diane’s interest in Black armed self-defense movements like the Black Panthers, or their lesser-known precursor and inspiration Robert Williams. The arc of the book mirrors the trajectory of the possibility of armed revolution in this country, which seems to me now essentially nil in the face of our militarized police state. Now that it’s essentially impossible, the idea of armed revolution here is almost exclusively a right-wing fantasy; our government is too well armed and funded to be taken down by the people, so-called. The only “revolution” possible right now is from within government, and the Trump era has given us a glimpse of what that will look like, if and when it comes.

But what strikes me about the earlier Revolutionary Letters is how truly revolutionary they are. A veteran of the earlier Beat counterculture, Diane was 34 when she started writing these poems, 37 when the first City Lights edition came out, quite young, it seems, to 49-year-old me, but considerably older than your average hippie. In a sense, the book is an anti-hippie manifesto, not that she’s against the denizens of the late ’60s counterculture—they are, in fact, her people—but that she’s old enough to know that “flower power” wilts before the fire power of the state. The state is never going to cede power without violence. Revolutionary Letters thus presents itself as a handbook for revolutionary activity, as well as an attempt to educate a generation of youth who sincerely want to bring about societal-level change but are utterly naïve about what that entails. This education takes many forms; sometimes it’s literally advice, from what to stock in your pantry to survive if supplies are cut (#4) to what drugs to keep on hand for what situations (#5). Other times it more broadly concerns revolutionary strategy (#15), advising the student protestors at Columbia University or in Paris to “take / the media” to explain what they’re doing and why, “to combat” “70 years / of media conditioning.”

This latter item points to one of the great poetic achievements of Revolutionary Letters, which is Diane’s own facility in seizing the means of communication—in this case, language itself—by redefining the conceptual terms of engagement. We see this, for example, in letter #8, which begins: “Everytime you pick the spot for a be-in / a demonstration, a march, a rally, you are choosing the ground / for a potential battle.” Redefining a protest as a “battle,” particularly among the “peace and love” youth culture of the turn of the ’70s, is not only a radical rhetorical move but also an entirely realistic assessment of the potential police response to even a peaceful protest, as we’ve seen recently enough with the Black Lives Matter protests, and #8 is a still-relevant set of instructions to avoid being kettled when the authorities decide to crack down. But the revolutionary strategies Diane outlines are by no means limited to escaping conflict. Are you ready to kill? Diane is! Or at least, she advocates it as legitimate revolutionary activity, in letter #9, in which she proposes to “kill the head of Dow Chemical . . . make it unprofitable for them,” in the face of the company’s manufacture of napalm to profit from the U.S. war against Vietnam. This is counterterrorism 101: exact a higher price for each injury inflicted, so the terrorist can’t afford to keep inflicting injury. Obviously, such a viewpoint entails redefining the actions of the U.S. government and its supporting military-industrial complex as terrorism, which, of course, they are.

Lest we think this advocacy of counterterrorism is merely the fire of youth, we might look at the first new letter printed in the 2007 Last Gasp edition, #71, which begins:

A life for a life, a young black

woman’s voice said to me on the

phone the day George

Jackson died in prison and I

said even twenty, a hundred for that

one would be cheap. Even a thousand.

This is clearly something Diane still believed on a fundamental level, and she would explicitly take up the theme of redefining government activity as terrorism in letter #80, subtitled “GOOD CLEAN FUN”:

What happened to the Hampton family in Chicago—

Fred Hampton blown away in his bed—

would you call that terrorism? Or the move kids in

Philadelphia

bombed in their home. Or all the stories we don’t know

buried in throats stuffed w/ socks, or pierced w/ bullets.

Wd you call it terrorism, what happened at Wounded Knee

or the Drug Wars picking off

the youth of our cities—as they already picked off

twenty years ago—or terrified into silence—the ones who shd

be leading us now—

you know the names.

What was COINTELPRO if not terrorism? What new initials

are they calling it today?

Even later she equates America itself with terrorism, writing of “the terrorism that is the USA” (#94). I don’t mean to overstress this particular element of the book, but I raise Diane’s view on state terror and counterterrorist violence as one of the more extreme positions she adopts in Revolutionary Letters to illustrate the degree to which she was not merely playing at revolution. She was wrestling with the hard questions of what it entails and the conclusions she drew weren’t always pretty. Indeed, she doesn’t even spare herself in the calculus, having written in letter #12 that “every revolutionary must at last will his own destruction / rooted as he is in the past he sets out to destroy.” The willingness to take a life or give your own that Diane advocates might sound at odds with the Buddhism she espouses, but the one is actually rooted in the other, as she notes as early as the second letter:

The value of an individual life a credo they taught us

to instill fear, and inaction, “you only live once”

a fog in our eyes, we are

endless as the sea, not separate, we die

a million times a day, we are born

a million times, each breath life and death

Here Diane seems to suggest that a Buddhist conception of reincarnation in fact underwrites her willingness to put lives on the line in the name of revolution. I imagine LSD may have nourished this cosmic vantage, which is reiterated in various forms throughout the book, though I never had the chance to ask her. But such passages feel like acid to me; it’s one thing to learn about Buddhist return but quite another to express such a belief as an insight.

The character of Revolutionary Letters inevitably changes as it continues through the decades, becoming less a handbook for revolution and more a protest against the ongoing injustices of capitalist society as the possibility of a popular revolution in the U.S. grows increasingly remote. The terse one- to two-page dispatches of the first two editions meanwhile give way to poems of widely varying forms and lengths. It would be hard to imagine letter #82, an eight-page poem of Creeleyesque short lines debuting in the Last Gasp version, appearing in the original edition, though by the time we arrive in the overall sequence, the letter hardly seems out of place. But if it grew less cohesive, the book nonetheless gained the power of continued relevance, not simply in relation to new subject matter like the First and Second Gulf Wars, but also in relation to its original moment. As we’ve seen her assert in letter #80, the consequences of the events of 50-plus years ago continue to play out today, and the battle is still the same battle, whether or not it can be waged in the same way. To have ended the series while she was still alive would have defanged it by relegating it to history. No wonder she held onto those proofs! But if her death has finally accomplished this turn from a living project to a historical book, Revolutionary Letters is a remarkably up to date one.

*

On Friday, 8/27/21, Revolutionary Letters came back from the printer, meaning it’s now available from City Lights, though the official pub date is still a few weeks off. Now that the book exists, I’m finally starting to enjoy it, though of course much second-guessing of individual decisions has ensued. But even that is already starting to fade. The book has been selling briskly at City Lights, as folks have been waiting for it since we announced it. So it’s out of my hands now and out in the world, where it belongs. I don’t know how else to end this piece. To paraphrase something Diane said at the close of a City Lights event for the book Semina Culture (2005), “There is no end, because we’re still talking about it.

out in the world

———————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Garrett Caples is a poet and writer who lives in San Francisco. He is an editor at City Lights Books. His most recent book of poems is Lovers of Today (Wave Books, 2021).

Diane di Prima (1934-2020) was one of the most prominent poets of the Beat Generation. Her books include Revolutionary Letters (1971-2021) and Spring and Autumn Annals (2021). She was the poet laureate of San Francisco, the co-editor of Floating Bear, and the co-publisher of Poets Press.