One Who Sits Beside: Sylvia Matas Reviews dg nanouk okpik's Corpse Whale

At the back of dg nanouk okpik‘s Corpse Whale there is a “loose Inuit glossary.” Qarrtisiluni is defined as “sitting together in darkness waiting for something to burst.” okpik is Inupiaq-Inuit from Alaska and her poems are written in English with the inclusion of Inuit words, sometimes when there is no English equivalent. With both languages on the page, the reader is reminded of the complexity of life in Alaska where Inupiaq ways of living continue to be affected by ongoing colonial presence. okpik’s poems are set in a world where a shaman’s ceremony exists alongside cyberspace; where satellites as well as ancestral spirits circle the earth:

Qarrtisiluni sitting in silence when all things

and all beings reach back into time

before iron and oil.

Many of the poems are irregularly spaced with words floating surrounded by white space. This evokes a sense that the words, language, the human voice hang in the vastness of space, in the arctic and the cold universe. It makes the human voice feel quiet and small, surrounded by endless expanses of space and time in all directions. These ruptures of the voice with unpredictable spacing give okpik’s words a haunting feeling.

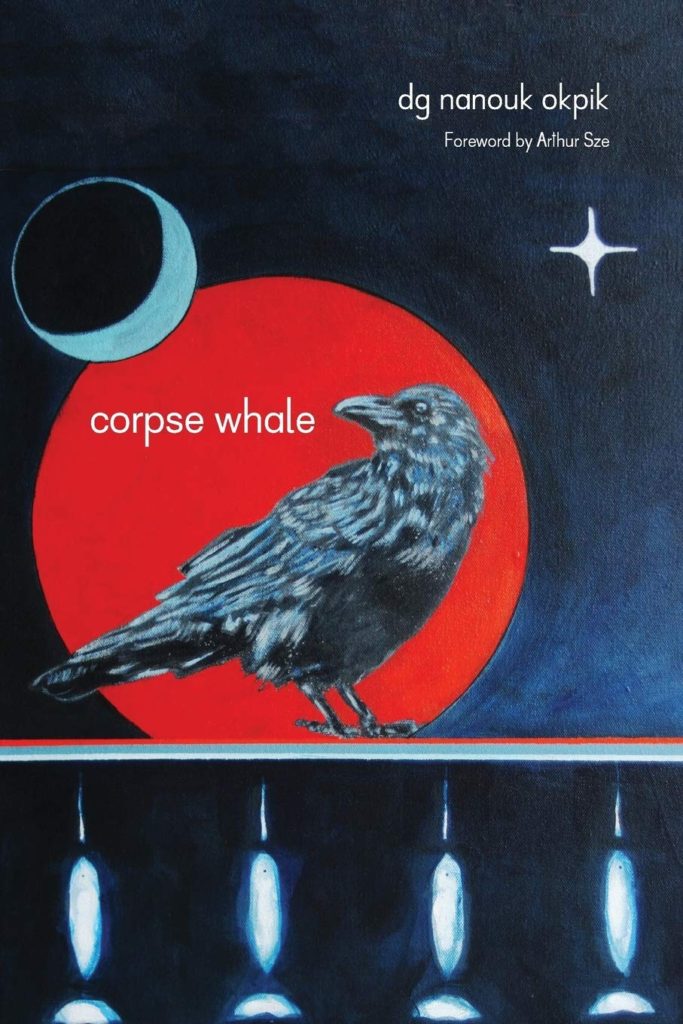

There are many references to the sun, moon, and pole star evoking a cosmological time frame that exceeds human presence on Earth. This gives the impression that a raven flying overhead is a fragile skeleton covered for a brief moment in flesh and feathers. Living whales, polar bears, and wolves are the fossil record of the future.

Time, in the world of Corpse Whale, does not move in a linear direction. There is a poem for each of the calendar months, but somehow the book feels like moving through a calendar year, a single lifetime, and all of time simultaneously. Past, present, and future blur, giving the impression that the speaker is somehow not yet born, but already a ghost. She was “born / on the brim of an ice casket.” The book begins with origin stories and ends with death or transformation into the spirit world, but throughout the book the speaker’s body forms and disintegrates again and again. Her body was “forged by sea salt / by snow hammered” and “decomposing, cast down in the dark.”

The border between life and death is not clearly defined. At times the speaker sips tea in a plank grave under sod, detaches from her carcass to smoke a cigarette, and covers her eyes with “legs crimped in a mock casket.” The speaker moves though the world of the living, the dead, and somewhere in between, frequently referring to herself as “she” and “I” at the same time. She is not bound by one body, one identity, or one location in time or space. “she/I wait/s for the next ten thousand years of / fossil replica” Her subjectivity shifts and transforms from internal to external, to animals, and to other beings. In “Addled,” she speaks from the perspective of a whale:

you bite into her/my scalp down to the grey

“ her/my breastbone snaps snaps rings allowing my chambers to fill with blood crushes down like compressed throats striking air litmus red

I stomach both lungs drowning in skin

And as an observer of the whale:

a winch reels in thought of tinkered eternity

and a whale losing her long-haired cheese clothed

piece of baleen floats smelled faintly floats ashore on Crow Island

In other poems, the speaker’s feet “turn cloven” and she has “antlers/ like long mesh conduits coaxing my head.” She dreams of flying with a gyrfalcon and they seem to merge into one being, the bird’s call and the speaker’s throat song a single vibration. The speaker describes a self that is not static or singular, but part of the world and connected to all things.

In “Stereoscope” she asks,

How do you mention

one by one our place-names

and dates of birth by labelling your glass boxes?

How do you print on heavy flat paper

the artifacts of Nuiqsut which makes me pull apart my cartilage?

She challenges this colonial worldview that seeks to separate and categorize, to take and identify. With its emphasis on individual needs and exploitation of natural resources, this worldview has led to devastating damage to the land and to the Inupiaq way of life, a world where trees burn, the permafrost thaws and the sea warms, leading to changes in animal behavior. “Jellyfish plunge into cement splashing” and

Musk oxen cant guard nuclear

grasslands from brown air thin water.

And in “Oil is a People,” the speaker witnesses bulldozers razing the land, the flames burning in the wind, “oil dripping on the tundra.” Images of cadavers, fumes, smoke, and ash elicit feelings of dread and an ominous vision of the future.

The past emerges into the present in “Her/My Arctic Corpse Whale” as the speaker observes “the Inuit skeletons are rising like brittle”: an image that brings to mind bones literally emerging from the thawing permafrost, but is also a reminder of the presence of ancestral spirits. The songs of the ancestors still ring across the land and water, but at the same time steel engines from ships shrink sonic space for whales, rendering their calls to each other less audible. There is a sense of loss and urgency as

she/I try/ies pushing,

pushing, and shoving the sinew back into the threaded

bones of the land.

In her talk at the Salish Kootenai College, okpik described a storyteller as “one who sits beside.” Rather than placing herself at the center, she shifts the perspective of the speaker, conjuring a world that contains within it endless points of view, beyond human, beyond living, and beyond the present. She said, “I’m just a vessel, a hollow bone that these stories come through.” okpik channels these stories into poems that hypnotically and urgently transform and expand our sense of time, space, and the self.