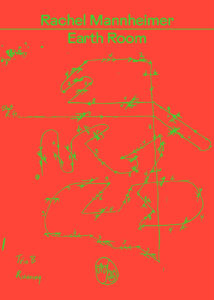

Niina Pollari Reviews Rachel Mannheimer's Earth Room

How can we write about art without knowing our readers know what we mean? There is an obvious challenge inherent in describing temporal works, like live movement, which can never be recreated. But even when writing about art that takes on a more static form, it’s still hard to convey the scale, the movingness, maybe even the sublimity–especially where, for example, the work’s massiveness (either in concept or size) is a part of its appeal.

I have never written at any length about visual art; the endeavor intimidates me. Yet I admire writers who take on the task. At the same time, no part of me wants to read journalistic takes on art. When I read about art, I want to read about its movingness to an individual human being, and the ways that the individual has continued to digest it over time. To me, this experience-based art writing works particularly well in poetry, the slipperiest of the static forms.

In recent years I’ve enjoyed several collections working in this mode, including Diane Seuss’s Still Life with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl, and Mary Hickman’s Rayfish, both of which foreground works of visual art (Rembrandt and Chaïm Soutine, respectively) while also unraveling personal narratives. To me, the effect is enhancing to both art and poetry. Viewing art is so often about the subjective experience, and if you can’t be there to view it, the next best thing for an empathetic creature is to read about someone else’s experience. So I picked up Rachel Mannheimer’s Earth Room knowing that my particular interests would likely make me a good reader for it.

Named after Walter De Maria’s Earth Room, which is (in its New York iteration) a blank gallery filled with 250 cubic yards of meticulously combed soil, blurring the line between nature and installation, Mannheimer’s collection is filled with descriptions of the various artworks and environments that her narrator (a version of Mannheimer) witnesses in different geographical locations. All the while, muted biographical details emerge to bring depth to the narrator’s art viewing as the book progresses. The first poem establishes many of the book’s main ideas: the viewing experience; fear of loss; the distance within interpersonal relationships, which, born of subjectivity, can never be breached. The narrator attends with her partner an exhibit of Laurie Anderson’s To the Moon, a VR performance of sorts consisting of an imagined vision of the moon co-created with a video game designer and using tropes from across media, including mythology, literature, and sci-fi. But the narrator feels she is missing something about it, whereas her partner has what she perceives as the more complete experience:

That’s how it was, sometimes, living with another poet.

Like we could both put on headsets and wave the controllers –

arms outstretched and triggers depressed – but for me alone

nothing happened.

Just the presence of someone else (another writer!) influences the narrator’s feelings about the exhibit. Were he not in attendance, how would she experience this virtual moon? They are residents in the same museum, wandering the galleries by day but sleeping separately at night, because he’s sick (another distancing factor). There is sickness and death elsewhere in the book, too, on a personal and historical scale.

“What did you see on the moon? I demanded as he left,” and then, later: “I’m imagining the poems Chris will write.” This profoundly Coleridgian moment, where the experience lies in mourning a lack of experience, sets the stage for the rest of the collection; as Coleridge writes in “Dejection: An Ode,” also about the moon and stars: “I see them all so excellently fair, / I see, not feel, how beautiful they are!”

Let’s say (as it’s generally acceptable to say) that art doesn’t exist as such without a viewer, and that to witness a piece of art involves some kind of transference between the art and its audience. Whether or not there’s a perceived personal shortcoming in the experience that a viewer has while viewing an artwork is one open question. But what about writing about art, when the recipient of the narrative is not there to see the art? Mannheimer seems to opine that the viewer’s presence is not necessary for them to derive enjoyment, a view with which I agree; in a later poem titled “Los Angeles,” she writes:

My theory of art

is that there should be pleasure

in just hearing the concept,

but added pleasure

in seeing the thing itself.

I have experienced pleasure in hearing about many pieces of art, and usually these pieces have to do with the experiential or situational, and my envy or desire for such: The Kelpies, a 98-foot horse sculpture in Scotland, for example, and Robert Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty,” a massive land sculpture located on one rapidly receding shore of the Great Salt Lake. Descriptions of these works have left me with a sense of smallness that I simultaneously enjoy and am horrified by, and I hope to see them one day. Of course writing poems about art requires much more than a description of the concept itself, but I think in order for the metaphor to work, the description does need to be clear. Mannheimer executes with great clarity.

In addition to art, the book depends on place, just as the Earth Room installation needs the earth itself. Mannheimer examines place like she does art: with a critical eye, and pre-existing context as a viewer, both personal and political. The narrator visits a concentration camp site in the Tempelhof area of Berlin, for example:

Darkly, I had joked about the barbed wire curling

along the top of a nearby wall. But there actually was a camp here.

Forced labor for Lufthansa. Eleven were killed

in a Pittsburgh synagogue the morning we flew out –

the sanctuary where I might have prayed with Zev.

The past and present bleed into one another just as they do in life. Mannheimer makes no separation between them; this is the geological time of art, after all. She allows the proximity of personal observation, but that’s as far as she goes. Similarly, though there is personal grief around the loss of her mother present in this book, the personal is quiet, almost background, coming across in a few lines: “Why should I ever miss her less? / It’s only ever longer since I’ve seen her,” the narrator says after looking at artworks of women and children in Berlin. I don’t need to be told any more, to understand that this is a book about coping with grief.

Climate change, too, is present, in the way that it is present for most of us: a premise or a fact, manifestations of which we notice in small or large ways around us. There are notes about it being unseasonably warm in places like Ithaca and Rochester: “Now it was December, but the grass was green and on Highland Ave the decorations seemed divorced from the season[.]” So, too, is present a minor commentary about human wastefulness in art: later, talking about a dance performance by Pina Bausch’s company that required 4000 gallons of water: it was “trucked in from New Jersey and meant to be reused each night” but “turned out to be contaminated. New water was found.” Of course it was, in 1985. But what happens in drought conditions? Nothing more need be said for the point to be obvious. Mannheimer does discuss Smithson’s Spiral Jetty as well – how it was “for several years submerged under the Great Salt Lake. Then it reappeared.” This reappearing is an understatement. At the time of this writing, the lake is at its lowest level in recordkeeping history, leaving Salt Lake City vulnerable to the toxic dust formerly kept contained by water; the lake levels are at least five feet lower than it was at the construction of the Jetty. On a Google Earth view, the rounded fiddlehead end of the sculpture stands some distance from the edge of the water.

While revisiting this book, I was also simultaneously reading Elvia Wilk’s essay collection Death by Landscape. In it, Wilk quotes another writer, Daisy Hildyard, in discussing the idea that every contemporary human being has an increasing global awareness of themselves, a “second body” of sorts (the title of Hildyard’s essay on the topic). This second body is “tethered […] to microbes, mosquitoes, whales, ice shelves, landfills, and annual average rainfall, as well as, of course, human political and social formations.” To be in possession of this second body means you’re living with your present self, eating, sleeping, and interacting with your small world and its sicknesses and pleasures, but also “constantly implicated in and influenced by ecologies beyond the individual self.” Being aware of these two bodies is “to experience a constant toggling between self and world, which can be enlightening but can also bring on a sense of horror.”

I feel this at a fundamental level; I no longer believe that we can make successful art in an era of climate collapse without acknowledging our place within the system, whether or not the art is “about” that, so I tend to read everything with this lens; this is the other thing that made me a particularly appropriate reader for this book. Though Earth Room stops short of the horror, as a work, it is totally aware of its systemic self; Mannheimer uses geography, art, and history to examine, though not judge, these entanglements at scale.