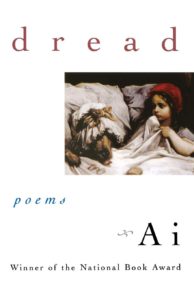

Ray McDaniel Reviews Ai's Dread

Here’s a discouraging thought experiment as brought to you by the Homeland Office of Ontological Terror:

Consider the possibility that the quality of any random poetry sample is determined exclusively by its location on the asymptotic curve of the reader’s familiarity with poetry altogether.

This axiom suggests a possible truth that is starting to erode the frequency and quality of my sleep: maybe poetry is only good when you haven’t read enough of it. And maybe the more of it you read, the less rewarding that reading becomes.

I offer this unhappy hypothesis because I cannot decide if Ai’s Dread is as insufficient as I imagine it is, or if my evaluation of its failures is contingent upon my familiarity with her prior successes.

I am very fond of her Cruelty (1973), I am pleased by the textures of her Killing Floor (1979), there are moments in which her Sin (1986) is compelling. Her Fate (1991), however, is a bit dim; her Greed (1993) gets the best of her, and her new and collected Vice (1999) is more or less what it claims to be. And now her Dread, the title of which nearly prohibits further comment.

I choose Ai for this essay-review because she presents a peculiarly lucid case study of the “career.” She established in Cruelty a formal shtick, an approach that borders on a manner; she’s clung to it with a tenacity that once struck me as ferocious but now seems like a failure of imagination. Her method, for those unfamiliar with her work, is a deliberate perversion of the standards of the dramatic monologue—since the start of her “career” (I’ll justify those quotes later), Ai has inhabited the voices of the dead and the living as if her speakers occupied some irresolute state between mortal and divine (or more often damned) sagacity. The trick of the dramatic monologue depends on the question it implicitly raises about both the prompt of the speech-act and the position of the speaker. In her most provocative work, Ai lured the reader into these quagmires of the indeterminate and then punished them for their voyeurism; she was David Lynch before David Lynch was. All of her characters were dead, wrapped in plastic, even the living ones; all the unknown folk wore the abused make-up of the drunken star; every voice was a tin bucket echoing in a hollow well. Her collective cast of characters thus seemed to be auditioning for the afterlife, narcotic by way of prophesizing the necrotic.

Given Ai’s resolutely consistent subject matter (death, murder, poverty, deprivation, the residual tar of love, pedophilia, rape, mutilation, the hollowness of fame and desire, fire), this affectless, monologic parade often created poetry of a genuinely sinister quality. It is difficult for me to reproduce the simple creepiness of her early poems; I think in particular of her boy-killer and his fish-cold appraisal of his own murderous charm, and of her Aguirre and his dead-hearted threats to a god in whom even he seemed to disbelieve.

One of the more dizzying aspects of this initial force was the degree of auctorial absence; there was no Ai, one never had the feeling of being subject to an actual poet (“ew!”) and (her actual experience (“boring!”).

The question now, of course, is whether Dread is evidence of Ai’s exhaustion, or of the exhaustion of the strategy by which she has made her name. I do not think, were I wholly unfamiliar with her work, that I would greet my introduction to Dread with the pleasure I afforded Cruelty; I cannot, however, eliminate the suspicion that I am the one suffering the exhaustion of overexposure—and that thought creeps me out as well.

So if it isn’t just me, how can I tell the infernal and sulfurous bloom is gone from this peculiar rose? At the risk of violating a tacit trust in the poet’s autonomous rights to self-determination, I would like to start with the dedication:

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED

TO THE SURVIVORS OF CHILDHOOD TRAUMA

AND TO GWENDOLYN BROOKS

The page count has yet to begin, and I am already a-squirm.

What unnerves me about this dedication (a space optimally preserved for sentiments that should not infect the poems that follow) is—well, see, goddamn. That’s it precisely: I cannot state my objection without relying on prior knowledge. Is there a readerly vantage from which I could glide over this dedication? Am I suppose ta? The truth is that I read these words and rolled my eyes and then immediately felt shame for rolling my eyes and then immediately resented being placed in such a position to begin with. The source of the irritation, of course, is both the breadth of appealing to “survivors’ and my deep unease as to the range of meaning that phrase could possibly contain. A dedication implies a degree of intimacy; survivors of childhood trauma does not meet the criteria of that proffered intimacy. And this is only aggravated by the specificity of dedicating the work also to Gwendolyn Brooks, a very intimate person indeed.

The cumulative effect of this hasty set of flinches and retractions is a loss of personalization; a sense that the mode of address is, if not insincere, certainly not very well customized to achieve the benefits of manifest sincerity.

This isn’t the optimal way to usher the reader into a sequence of monologues, for which impersonal intimacy is a treacherous oxymoron.

The poems themselves do little to mitigate this anxiety. There is a monologue from the point-of-view of a beat cop whose brother has perished in the collapse of the Trade Center Towers:

He’d stopped drinking for good

and I believed him, as I looked deeply into his eyes,

and saw a boy who having barely escaped

the inferno of family violence

would still finally perish in fire’s cold embrace.

(“Dread”)

Looking deeply into another’s eyes? The inferno of family violence? This isn’t weird; it isn’t even maudlin. It’s caricature.

A number of the subsequent monologues offer equivalent displeasures, including a second WTC piece, “Delusion”:

“There’s seaweed in your hair,” I said

and she replied, “I don’t care. I’m dead.”

Then she laid her head against my shoulder.

It was so hot, my blouse burst into flame,

I told her I wouldn’t let her down, I’d hold her,

But like all the other times, I let her go.

At the next stop, I got out,

but instead of walking upstairs

and taking Amtrak to New York City,

I stepped into the path of an oncoming train,

because I preferred to stay in the underworld,

with all the other missing boys and girls.

This is more effective, but even Ai’s gestures towards the strange (the blouse that blooms into fire) are effectively erased by the conventions of the “underworld,” undistinguished home of her undifferentiated “boys and girls.”

What Dread demonstrates at moments that rise above those detailed here is that Ai is simply a more vivid and uncanny mimic of evil than she is of those whose lives have been tainted or terminated by the agency of that evil. In “Disgrace,” a mother laments her daughter’s prospects while unwittingly revealing the very traits the infliction of which are most likely to impair those prospects. The speaker (suggested in the jacket copy as an approximation of the poet; this is by far the poet’s work most suggestive of autobiography) is a bit drunk, a bit surly, simultaneously prim, uncouth, comic and assaultive:

I’ve only tried to make her see how empty

what she thinks love can be.

That Martinez boy is half like her,

Mexican and Negro,

not a bad combo as it goes.

They’d have pretty children,

but I know he’d hurt her.

Pretty men are useless.

She needs a toothless old fool

she can control,

but some of them are cruel too

and use a young girl, yes they do.

I should let her get her kicks

on the old Route 66 of heartbreak, I guess,

but I am too old to clean up the mess,

no she’s going to college.

What this sounds like is a voice; distorted, both abbreviated and elongated, true, but still recognizable. What it is not is naked manufacture, an armature on which a ragged empathy is meant to hang.

Dread concludes with a sequence of monologues describing the professional adventures of the “psychic detective,” and in these poems I detect Ai’s impatience with her own methodologies. The psychic detective, of course, has a head full of Ai’s poetic property: murder, sexualized murder, god, fire, masturbation, failure . . . add them to the items catalogued previously. These poems read the way a Bloody Mary drinks when taken through a mouth full of smashed teeth; it’s difficult to discern the subject from the sensation. A derivative of Black Lizard and James Ellroy, the scenes of the psychic detective’s investigations are ripped through with haste disproportionate to Ai’s usual narrators. At one point the detective states

“I’m packing it in, Bob,” I say,

“I’m tired of ‘seeing’ things,”

and in some ways I hope this avatar of reconstructive memory, doomed to inhabit other people’s most visceral miseries, is indeed a proxy for Ai herself.

The poet is slowly becoming herself; she has begun to enucleate her “I.” Paradoxically, her embrace of this shift restores to her the force previously at her command; it is when she seeks to reproduce the aspect of her early method that she fails.

I isolate the word “career” to cast doubt on the merits of such a thing, indeed upon its very possibility. The phonetic irony of Ai’s mono-moniker has always been her consistent identification with a project that defeats identity; if she (if all poets) were to be released into the wilds of enforced anonymity, who knows what might be written?

(This last question comes to you from the Office of Office of Ontological Terror, your tax dollars funneled to the construction of worlds worth considering because of, and not despite, their apparent impossibility.)

COMMENTS:

Tod Marshall May 16, 2003 at 2:49 pm

Ray,

Your review is good. I reviewed FATE a few years back (found it lacking), and I agree with your summation of her career: there was something in those early books that has now atrophied. I haven’t read her work since then–

Anyhow, stimulating and smart–

Tod

Janaka Stucky May 16, 2003 at 3:34 pm

I’d like to applaud Mr. McDaniel’s candid review of Ai’s new book of poetry. It is not often that new poetry receives the honest criticism that it usually deserves. In the difficult business of poetry publishing, many reviewers and editors seem to be more interested in mutual back-scratching than in genuine quality control. Of course the reader then suffers, and as a result loses his trust in the judgment of presses and critics. In giving a direct and thorough review of this book, Mr. McDaniel seems to have done his little part to counter this downward spiral. As a poet and reader, I would like to thank him.

Jorge Sanchez June 2, 2003 at 10:04 am

Mr. McDaniel:

Another fabulous performance from the First Man of Contemporary Poetry –Huzzah!

At least we know there’s somebody out here on the velvety dark expanse of 21st Century American verse, even it is a dude with a flashlight who’s none too happy to have to deal with all the mewling, drooling vegetables,

-J