Christine Hume Reviews Lance Phillips' Corpus Socius

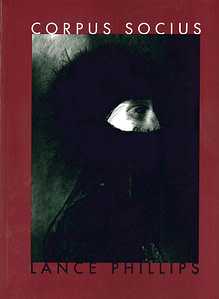

Lance Phillips

Ahsahta Press, 2002

Reviewed by: Christine Hume

March 21, 2003

// The Constant Critic Archive //

Emily Dickinson’s lines

A bomb Upon the Ceiling

Is an Improving thing

It keeps the Nerves progressive

Conjecture flourishing

articulate my experience of reading Lance Phillips’ Corpus Socius. Phillips’ intense rhetoric of fragmentation and condensation elides narrative and image in the service of spiritual questing. His poetry is so pared down and so fiercely material, it’s quite off the map. If you exploded Hopkins’ God-charged world, his “sweet especial rural scene,” and reassembled the remains around a new understanding of the physical self, you might come close to imagining Phillips’ work.

Epigrammatic yet interlocking, Phillips’ lines embody the title’s paradox; the lines nose in on, and create a context for, each other while remaining adamantly independent. At the risk of providing a great disservice to the book’s unity and expansive method of speculation, here are some excerpts:

The cell’s moral am: yes

Different from private is and the bee is cross-sectioned

*

Milkeye along the weir’s a tract freer.

*

The red procedural branch

Act supersedes her hair as her mantle

*

Sometimes word, sometimes mind, sometimes Jesus, sometimes door

*

—’Aql

—A excending her lip as the volume three strands treads back

ownership-iris to possession-iris

—The lowest yellow surface

His game is tight: cryptowords, homophones, sonic echoes, etymological explorations percolate a subliminal sense. Equations (“treed is lyric”; “spine’s a stem”) point to a defining impulse and a desire to actualize concordances; the double motion of Phillips’ use of etymology and Latin words is a typical strategy in the book. The lexical archeology here seeks origins and authoritative meanings at the same time it violates those historicizing tendencies by insisting on temporality and contextuality. Phillips’ composting of word-parts and letters, archaic and foreign words, obsolete utterances and neologisms also defamiliarizes language enough to instantiate a forceful materiality. These poems call on our intellect and disarm our habitualized intellectualizing reflexes. Their sensual pleasures accumulate, their physical delights “shake dove[s] from endurance.” In other words, they materialize abstractions in much the same way Hopkins’ work does. Midway through the book, Phillips floats us the emblematic line: “so means the surface.” Here “means” means in at least two ways—it roughens the surface so allowing texture and depth, but the line also allows us to skim it, to let the surface of language offer meaning. The line’s sibilance hisses, it sings; its prosodic twoness mirrors a linguistic one. Iris or irides that peer out from many of the poems make the doubling of words—”Isle/I’ll”—and sentences—”Doe hears a possum / Do I over a bee’s posture” proliferate. (Irides is the plural of iris, but also the first part of the word iridescence, a word that certainly describes Phillips’ work: play of glittering changing colors, resonantly multidimensional. Irides perhaps also inverts or converts Hopkins’ famous “outrides”—the extrametrical syllables that go uncounted in his sprung rhythm.) Another example of contracting the abstract into the concrete: the word “veery” could signal a trope as in a turning or veering (an adjective) and a thrush (a noun). So the thrush is veery today; so Phillips re-examines the relationships between body and mind with his eye ultimately trained on the spirit. Phillips takes up Hopkins’ task of casting the poet as philological archeologist and spiritual attendant. To this end, like Hopkins’, Phillips’ work invents its own language as it goes—lexicons and grammars that seek to articulate and to create that which remains outside of conventional or conventionally poetic uses of language. Indeed, “The tongue’s little more a sun” here; you don’t just read this work, you feel it as a foreign tongue in your mouth.

And who doesn’t like to feel a foreign tongue in her mouth?

Phillips’ investigation of natural and synthetic structures relates the title’s “corpus” to its social nature, its subjection to ethical, spiritual, and biological principles. While this may sound like a form of belletristic connoisseurship, Phillips’ practice is rather rooted in a desire to shore cultural fragments against spiritual ruin. The language is dense and material but broken and, as in Celan’s late work, every word is edged up against an oceanic silence. The dogged naming in these poems ballasts an incomprehensible, necessary silence. In it, language becomes an object of speculation itself, a living organism with its own internal laws and powers of generation. This trust in economy and white space etches a vibrant line, one alive and vibrating, whose intense music hits a spondee then goes underground. These poems let us know that all that’s buried is not dead, and their rabbit holes of cross reference replicate the world “outside from the word.” This isn’t the lush place of Cesaire, Roethke, or Hopkins—it’s sparse and dense, the words appear as if “sucked up from the ground.” Formally, his quiet but aggressive skepticism comes crashing into his affirmative spiritual investment. “Yes” and “yea” appear a lucky and loaded seven times. Because of this twin tension and approach (and his two-fold vision of nature), Phillips extends Hopkins’ double-jointed embrace of tradition and invention. Gradually I got the hang of Phillips’ self-abnegating discipline and his seeming incarnational theory of language that shapes presence in grammatical, syntagmatic, and metrical form. So doing, they enact the swift movement of a mind caught in the act of perceiving.

His minimalism is rare and refreshing in a contemporary setting that insists on beating the Baroque horse unto prolix death. In the midst of the dubiously avid wars between avant-gardism and “mainstream,” Phillips finally gives us something to shut up and pay attention to. His ecosystem doesn’t register the morality that governs the predominant schools of decadent zany reveries or self-serious political agendas. His tactics are tough but humble, elliptical but not coy. Readers, live with this book a little, let its enchanted complexities have their ways with you. Here you will find a revivified lyric; as Hopkins did, Phillips leads poetry forward by taking it through the back door.

COMMENTS:

None.