Poem Without Beginning or End: on the Ramayana and Vivek Narayanan’s After

I think you should read Vivek Narayanan’s After, which is an erudite, funny, chaotic, absorbing book of poems that talks with, alongside, and back to the Ramayana of Valmiki. But you might not be sure. You might be saying, “What if I don’t know anything about the Ramayana, or India?” or “What if I never studied Sanskrit?” or “Who is this Valmiki guy?” or “It’s a large book. Will I be able to fit it in my bag?” If portability is your issue, please go get a bigger bag. For the other stuff, let me—Ramayana geek, poet, person who spent actual years learning Sanskrit—offer some assistance.

First of all, it’s not the RAM-a-YAN-a. For those of you new to this text or to Indian languages: curl the first R a little, letting the tip of your tongue hit the back of your upper front teeth very briefly. It takes some extra breath; you might feel your stomach contract. Do that a few times, just the R. Got it? Okay. Now you’re going to change the stresses, and probably the way you’re pronouncing those vowels, entirely: RAHM-EYE-uh-nuh.

It’s really two words: “Rama” (rhymes with drama), the name of the god-hero involved, plus “aayana,” which is often translated as “journey” or “path” but also means “coming” or “approach.” A Ramayana (there are many) tells the story of the hero’s journey from the city to the forest as he searches for his wife, Sita, and finally conquers her abductor, the demon king Ravana, in battle. Or else it tells the story of the hero’s approach—Ravana, Rama’s coming to get you, and Sita, he’s coming to save you. Or else it tells the story of god’s coming into the world, when the Hindu god Vishnu “takes avatar” (i.e. descends in a bodily form), as Rama. His goal (which is another translation of “aayana”) is to restore dharmic balance in the cosmos—to set things right.

The Ramayana is often described as one of the two great classical epics of South Asia, but unlike its longer cousin, the Mahabharata, it exists in hundreds of versions, none of them original or central. The poet and scholar A.K. Ramanujan, in his groundbreaking essay “Three Hundred Ramayanas,” writes that “the story has no closure, although it may be enclosed in a text.” The earliest surviving textual version, the Ramayana of Valmiki, has a special cultural and religious status by nature of its language—Sanskrit, the sacred language of Hinduism—and its age. Valmiki is known as the “Adi Kavi,” or First Poet, and is a legendary figure who both authors the text and appears within it. Scholars date his version to the early centuries CE, but the story is older still; in turn, the many others that have cropped up over the past two millennia are sometimes indebted to Valmiki, sometimes not. Hindu Ramayanas tend to interpret Rama as god, and the story as one of dharmic restoration. Jain tellings emphasize nonviolence and control over desire, and argue that the Hindu versions are misrepresenting Ravana, who they instead portray as a tragic antihero, a could-have-been undone by lust. Some versions tell it selectively, emphasizing the parts that interest the teller, such as the 16th-century Bengali woman poet Chandravati, who leaves out most of the battle scenes but spends extra time on the suffering of Sita. There are Buddhist Ramayana stories and Muslim ones. There are versions that affirm traditional hierarchies such as gender and caste, and others that use the story to sharply critique those norms. In fact, the Ramayana is such a well-known narrative in South and Southeast Asia (and in those diasporas too), that it has become an effective way to talk about all kinds of things. Do you want to discuss ethics, gender, power, love, nature and the environment, inequality, or violence? There’s a story or character in here for that.

That’s not to say that the story always offers answers—part of its power lies in how messy the Ramayana can be. Because it has been around for a few millennia, it has unfolded in different cultural contexts, and religious worlds. The result is that it doesn’t always cohere perfectly or behave as we wish. The Valmiki version in particular is full of troublesome inconsistencies and moments of out-of-character behavior. Rama sometimes does things we don’t expect of a perfect human (let alone a god), and readers and tellers of the Ramayana have always had to reckon with these tricky bits. The scholar Linda Hess has written about the practice of Ramayana readers writing to an expert, Dear Abby-style, with their concerns about the story, which one such expert refers to as “Lover’s Doubts”: Why does Rama not once but twice send Sita off into the forest based on baseless rumors of her infidelity? How could Rama kill the monkey king Vali in such an unsportsmanlike way, shooting an arrow from a hidden place? If Hinduism prizes nonviolence and vegetarianism, why do the heroes of this story sometimes commit violence when it seems not totally necessary? The Ramayana is full of characters and emotions that are wonderfully familiar, while it puts before us unanswerable questions, impossible situations. To keep talking about, telling, and thinking with this story thus becomes a way of being in community; a religio-philosophical practice; a kind of love.

***

Narayanan’s After is a loving continuation of this tradition, a deep and critical investigation of the story and its themes, and an invitation to wade in, slow down, and get lost. Can something feel entirely contemporary and at the same time very much like reading ancient literature? I think this book does that. A self-described “collection of poems inspired by Valmiki’s Ramayana,” the book is in English and also engages seriously with the Sanskrit of the source text and with questions about translation. Narayanan draws upon the structure of Valmiki’s seven books very loosely, compressing those seven books into four sections. After picks and chooses its episodes, retelling some multiple times and others not at all. Along the way are poems that don’t track directly onto the original epic, but use its motifs to engage with other, more recent materials. This becomes more marked towards the end of the book, in poems that speak to violence and torture in Kashmir; voice concerns about environmental degradation; critique attempts to historicize and politicize the epic; and bear witness to discrimination and violence related to ethnic, caste, and religious identities in modern India.

The book’s title can be taken as an indication of its relationship to Valmiki—not a translation, not a version, but something after: indebted to, elaborating on, in conversation with. Another clue about the title is buried in the endnotes, where Narayanan writes, “The title of Valmiki’s seventh kanda, Uttara, might be translated in several different ways, including simply After.” The Uttarakanda is quite different from the other books in the Valmiki Ramayana, and functions almost like an epilogue (many scholars also view it as a later addition to the text, one that seeks to tie up the loose ends and shore up the theology of the preceding books). Narayanan’s After can thus also be read as a modern epilogue to Valmiki.

Ramayana retellings tend to either reaffirm or challenge the religious or cultural notions that have gotten stuck to it, and in it, over time; to take the story as a kind of supercharged symbolic language and then use it to say something new; or to intermingle the mythic with the personal. In After, Narayan does all these things at once. He embraces a maximalism and simultaneity that are very natural to the story tradition to which he is contributing, and that also seem entirely his own. An incomplete list of forms and approaches he takes here:

lyrical narrative poems

lists, charts, diagrams, circles and arrows, circles full of arrows

commentary, both his own and other people’s

translations, both by himself and by other people

translation unpacked, with word meanings, notes, English and Sanskrit layered together

ekphrasis on Ramayana-themed art and other relevant images

images (see above)

documentary poetics

a musical composition scored in drawings

a bar graph about torture

comic book speech bubbles

visual poetry of many kinds

mini-essays

dialogues

prose reflections

erasures

Yes, After is deeply experimental, and that’s the point: Narayanan is writing into a tradition that has been told for a long time in visual, oral, and textual forms, and that has given artists opportunities to use those forms in wildly creative ways. See, for example, the miniature paintings that tell episodes from the story by showing the characters multiple times within a single frame like a comic book (some of these show up in After). Or the marathon recitations, seasonal performances, and TV serials that let listeners live inside the story for hours, days, or weeks at a time. The use of experimental forms in this book often has the effect of messiness, of showing us process, context, and temporality alongside the polished thing, the poem. In letting us see behind that curtain, Narayanan highlights a kind of slippage between story-world and real world that has been a part of this tradition for a very long time.

A less obvious but no less experimental aspect of After is the way it seeks out the difficulty in the Valmiki text it follows. Many modern tellings edit out what doesn’t suit the temperament (and time) of the teller; for example, the television version that riveted much of India in 1987 drew on many canonical texts, showing viewers a story that contained all their favorite elements while remaining coherent, and a bit sanitized. Narayanan does the reverse, taking on the parts of Valmiki that might confound or disturb us and exploring them thoroughly. Multiple poems about a single episode or character offer different shades of interpretation and underscore the ethical complexities of the text. A short essay asks unanswerable questions about Sita’s portrayal and treatment. Poems interspersed with details from sketches for 18th-century miniature paintings ask us to look closely and consider even minor actors in the story. Narayanan’s close attention to the Sanskrit original also lets us see into the weirdness of Valmiki, which, as an ancient text containing even more ancient stories and ideas, can get pretty weird. This can be great, as when he shows visually the explosion of Sanskrit words and connotations connected to a single plant (the “Lotus” page within the poem “Un Trou”). It can also be, let’s say, off-putting. Does Shiva really ejaculate all over the world in Valmiki’s telling? Yes, it’s mentioned briefly. Do we need a whole poem (“Shiva”) on ejaculating all over the world? Maybe not.

In keeping with Ramayana tradition, After is hefty (weighing in at 610 pages), and at times quiet and meditative, at times really wild. We’re going into the forest, it seems to say: try to keep up. Like Valmiki, Narayanan shifts gears as the story progresses, taking us from the relative calm of the first section (titled “City and Forest” and echoing the first three books of Valmiki) into progressively more threatening spaces and situations. In the second section (“Dreams and Nightmares”) we witness the untimely death of the monkey king Vali, then follow the monkey army as they are sent off to search the earth for Sita, under punishment of death if she isn’t found in a month. Narayanan takes us with them, “exhausting the forests / day by day // regrouping each night in growing despair / leavened only by intoxicants…” or getting lost in a cave “so dark you doubted // you were there” (“Un Trou”). In part three (“War”) violence often distorts and obscures vision, “all / beings tossed in it— // and they saw no longer the battlefield // only nebulas of dust…” (“They Saw No Longer the Battlefield”). That section closes with the 147-page “Poem Without Beginning or End,” in which Narayanan juxtaposes Valmiki’s battle scenes with docu-poetic materials related to Indian military and police activity in Kashmir and central India. By “activity” I mean torture and murder of civilians. The poem means to overwhelm and does so very effectively, showing both the extent of state violence and the specificity of its victims and perpetrators. The cave is very, very dark, and we are still in it. Go in and see for yourself.

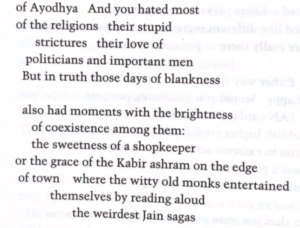

But I don’t wish to imply that this book is a dark one. Like the tradition it follows, After is a whole world, one full of horror and humor, monotony and surprise. Even as Narayanan insists on looking, and making us look too, at humanity at its worst, these poems land on tenderness and pleasure with regularity. Part of this is an attitude of both irreverence toward and attachment to the past, visible in the way he plays around with Amar Chitra Katha comic books, or riffs on Larkin: “They trip us up / the ancestors Don’t mean to but // they do” (“The Bridge”). We see that the citizens of Lanka are demons, but also that they are people who try to protect their children as the city burns: “behind the figure / alternate lives” (“Notes on the Burning of Lanka”). One of the pleasures of the book is how it shifts, just as we all do, from moment to moment, fear into joy into anger into fascination:

(“Ayodhya”)

***

One question I kept asking myself as I was reading After was, who is it for? Narayanan presents the Ramayana newbie with enough background material to stay afloat, including extensive notes and a synopsis of every book of Valmiki. The collection feels full and complex and deeply connected to the text and tradition it follows. But in the preface Narayanan expresses a hope “that the poems themselves contain everything that is necessary for their reading and comprehension,” and I’m not convinced that’s the case here—or that it should be. A reader of these stories who is brand new to the tradition could certainly read all Narayanan’s notes and summaries and get into it, but since the poems as often reference as retell, that reader will probably want to take After as the brilliant gateway drug that it is and read Valmiki or some other version alongside it. (In case you want to do that, but don’t have time for all seven volumes of Valmiki: I recommend Arshia Sattar or R.K. Narayan for modern retellings.)

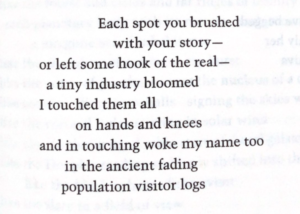

On its own, After seems to speak most strongly to others already in community with the Ramayana tradition—those who, like Narayanan, might have grown up with the story around them in some form, or maybe those who, like me, came to it later but know it pretty well by now. But even for those readers, one of the gifts of this book is the way it takes its time and sucks us into this tradition, in poems that roll around in the many possibilities of translation, inhabit specific episodes from multiple angles, or spend pages looking in detail at a single unfinished miniature painting of one scene from the story. One of the hallmarks of premodern epic poetry is its inefficiency: the leisurely detour into sidelong narratives, ruminations on the weather or the landscape, speeches that stop time and even delay death. Narayanan’s willingness to wander is one of the great gifts of After, and the experience of reading this book becomes, really, like walking around in a place that you gradually notice is marked with traces of the past, and in which you, too, are leaving a trace:

(“Nasik”)

In poems like this one, Narayanan lets the mythic brush up against the right-now, and that, too, is in keeping with the tradition. The Ramayana is ancient, sure. But it’s also startlingly present in South Asia. It pops up constantly in popular films (the last half hour of the recent Telugu hit RRR is explicitly Ramayana-themed), and has infiltrated language (for example, see Hindi expressions like “to tell a Ramayana,” i.e. to go on at length, or the idiom “Ghar ka bhedi, Lanka dhaye,” meaning “A spy in the house destroys Lanka,” i.e. be careful who you confide in). In a 2019 interview the Hindi film superstar Shahrukh Khan told David Letterman that his first acting role was in a Ram Lila, one of the many open-air performances of the story that are put on around India during the fall festive season. Khan played a member of the monkey army and his line was a single word at the end of a call-and-response: “Siyapati Ram Chandra Ki—” “—JAI!” (“To Sita’s husband Lord Ram—” “—PRAISE!”). It’s worth noting that Khan comes from a Muslim family. A Ram Lila performance is part of celebrations that are ostensibly Hindu but have for a long time been part of a public culture that isn’t limited to Hindus. In recent years the Ramayana and its characters have been claimed by and appropriated for the cause of Hindutva, or Hindu nationalism, but in the grand scheme of things (to which Ramayana narratives are always redirecting our attention), that’s a very new idea—and hopefully one that will pass soon. After is part of the bigger stream of this story-world, in which the water is available to all.

***

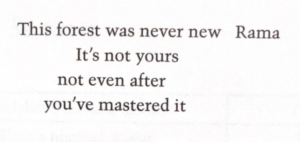

When I teach a course on the Ramayana, at some point I hand out a word-by-word trot of a verse from Tulsidas’s 16th-century Ramcaritmanas. We use a passage from the Sundarakanda, the “beautiful book”: a few lines in which the superpowered divine monkey Hanuman’s tail is on fire, which is the result of an attempt by Ravana’s guards to catch and punish him. Escaping, Hanuman leaps through the enemy capital of Lanka, using his tail to burn the place down. My students don’t have access to the medieval Hindi of the text, but the trot lets them take a stab at translation anyway, and in the process we see all the angles. Hanuman’s body takes shape, big and the lightest ever. Huge and feather-soft. Great, supreme, gentle. He leaps from house to house, or rushes from temple to temple. Maybe the houses are holy places, and temples houses for god. As the city burns, fathers and mothers shout, or people call for their parents, and they cry, “Save us now! Liberate us right away! Set us free this instant! Get us out of here, quick!” They talk about what they might have done to deserve this, which is to say, even while rejoicing in destruction, the poem is aware that there’s suffering here, that those people are like any people, like your own people. And then it’s over. Having overturned and set aflame Lanka, having flipped it upside down and roasted the entire place, having garbled it whole on fire, having made it topsy-turvy, having burned the whole mess, Hanuman leaps far away, runs further away, jumps away still, flees leaping, again, into the ocean, into the middle of the ocean, amidst the sea, into the center of the still sea. All this in a single verse, five couplets long: no wonder we keep coming back for more. Is it your first time here, or have you been away for a while? Either way, come in. After opens the door:

(“Here”)