Where Buddha Finds You: Brendan White Reviews Joel Craig’s Humanoid

Good poems can feel like people. Richard Rorty, months before his death, wrote that he regretted not reading more poems in the same way he regretted not making more close friends. Joel Craig realizes this effect in Humanoid (Green Lantern Press, 2021) with poems bearing the virtues of good conversation: digression leading to digression, bitchiness leavened with humane understanding, funny insights, surprising observations.

Some of Craig’s lines also just sound like good talk from a good friend: “I don’t know / how to describe / a bunch / of poseurs / thus / the word / poseur;” “your faux / histrionics / are pretty / funny / your real / histrionics / are quiet / -ly effective,” “we may be horrible people / but we’re all so / fashionably ambiguous / man / I know / you are not / my student / and I was never / your therapist.” “You” are invited to become an intimate friend, or at least a buddy with a similar sense of humor.

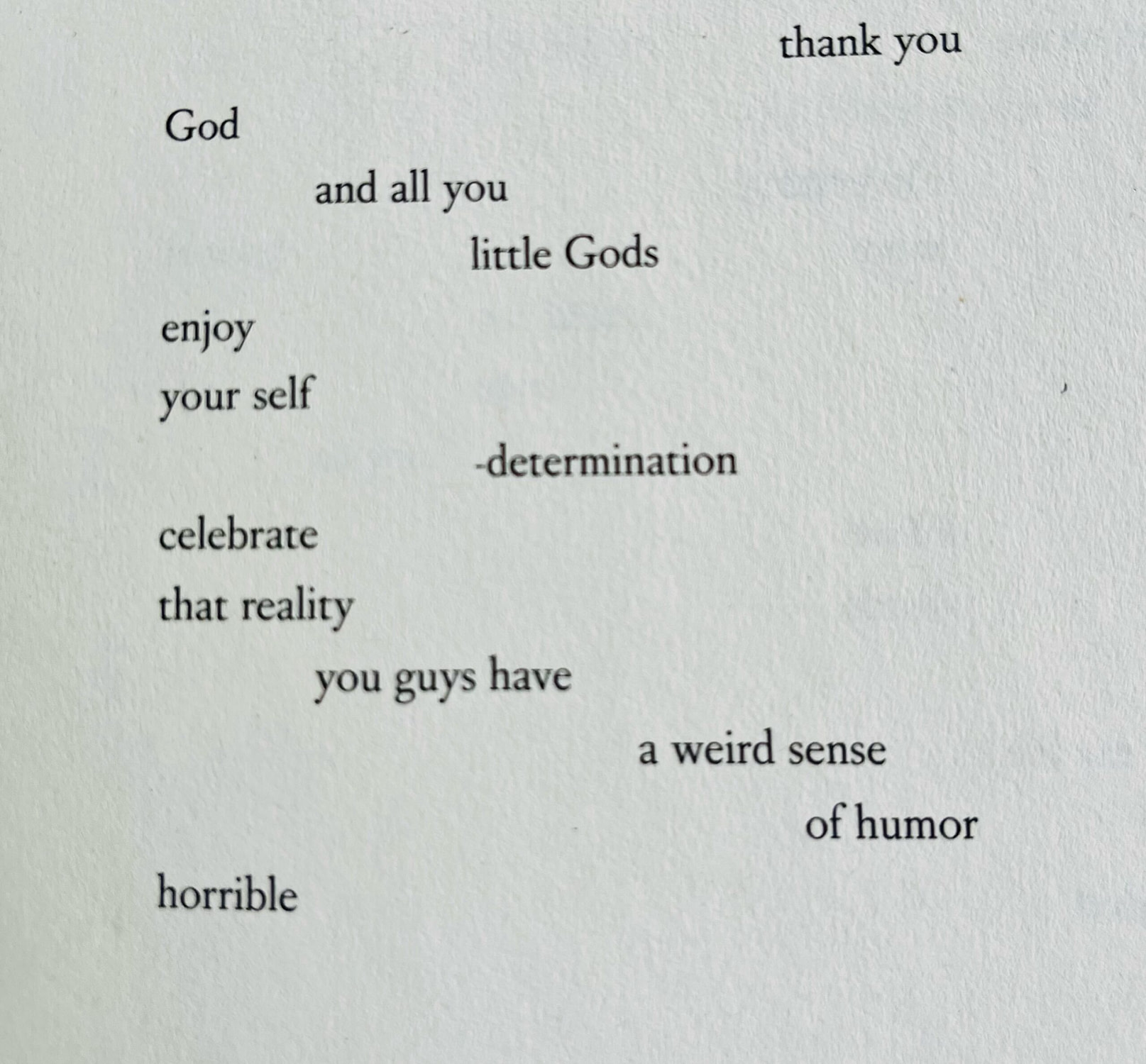

Humanoid has lots of jokes the reader is invited to be “in” on: “we may be horrible people / in the churning dream / is a line / you might have gotten / away with / in the ’90s.” The lines seem like they were written by someone who knows they’ve written bad poetry in their youth. And who hasn’t? But here Craig manages to make fun of the aesthetic missteps of the past while the choppy lines—my virgules can’t convey how your eyes must move around the pleasingly wide 7”x9” page to find the next phrase—also let you enjoy the line for what it is as it unfurls. Only then does the Critical Faculty appear, and we realize we have actually been derisively quoting some hypothetical out-of-date poet who would write such a thing and laughing about it with a friend.

I know of Joel Craig because he ran for many years the Danny’s Reading Series in Chicago. Humanoid ends with a list of eleven readings (mostly in Chicago) that occasioned the writing of each of the eleven poems in the 178-page book (which has many blank pages and a lot of negative space). The dates span 2014 to 2019. The poems in the book are about a world of face-to-face conversation that nobody knew was about to temporarily disappear, or realized was capable of temporarily disappearing in the first place. Many of the named series/venues are gone: Absinthe & Zygote, Wit Rabbit, Sector 2337, Craig’s own Danny’s. The poems seem spacey on the page, laid out as they mostly are with plenty of room around each two-or-three-word line, but they easily come together when read aloud. Craig even toys with other genres of declamation, like stand-up comedy: “I’ll start / like I’m telling / a joke / about the mystery / of another person’s / originality / you know / how you sit / on the bed / after you wake up.”

These poems are occasional verse—performances calibrated for a specific event—which have assumed an elegiac air almost against their will. Many lines speak of turning away from screen-based spectacle into a more sincere relationship with others: “how it it / possible / to love you / so dearly / in the flesh / while the you / who is presented / continuously / without beginning / or ending / depending / on no other / thing / only makes me want / to turn away / from the image / of all this light / that in the end / isn’t light at all.” Craig takes a sort of defiantly naive knowing approach to interpersonal conduct, coupling straightforward aphorism about being a good guy (“when surrounded / by loved ones / at breakfast / remember / the first rule / is do / no harm”) with a wry argument for its convenience: “duplicity / is hard / have you / tried it.”

Craig’s lines get some of their energy from the fact that they seem to always threaten to turn to face the camera and comment on themselves, but usually don’t, because he’s really talking to you. A lot of poetic energy is also generated by the mind of the reader attempting to hold component parts of the syntactical unit together, the pattern-finding part of the mind inclined to resolve sentences that keep on going and somehow become new sentences. An epigraph from Larry Kramer endorses reader-assisted meaning-making: “I guess what I’m saying, and hoping, is that a lot of inventive ways will be found to deal with any problems designing and producing my play might raise—that there is no right way and that, as in all theater, imagination is also one of the actors, and there are many ways to play the part.”

The way Craig takes sentences and grafts them to one another makes you feel as if you were eavesdropping in a crowded cafe and shifting your attention from the people on your right to the people on your left then back again. I would like to quote at length to illustrate this effect:

Craig’s first book, The White House (Green Lantern Press, 2012), did not look or feel like this. He didn’t deploy the sentence-splicing Humanoid method; the poems on the page looked tidier. The White House also had a poem about Fleetwood Mac and Humanoid does not, as far as I can tell. Two continuities: The White House seems to corroborate the fact that “the world” seems like Craig’s favorite concept, and the earlier book’s invocation of the “Buddha zone of the self” elucidates what Humanoid is trying to do. I take the “Buddha zone” to be the Green Zone you can retreat to, perhaps in meditation, where you become the observer of your life and thoughts rather than the actor or originator. A part of you that is separate; the part of you that can look upon your life and think this is happening to somebody else, someone in you who is not quite you.

Humanoid is a strange word. It’s an obsolete term for hominid, or evolutionary precursors to homo sapiens. In contemporary usage it almost always refers to aliens or robots—something uncannily almost-human-but-not. Craig seems to intend by the word the self in the realm of becoming; something along the lines of “we are all of us almost fully human, we just have to wait a little longer or try a little harder.”

A poem called “Development Hell” illustrates his approach to this theme: philosophical concerns salvaged from jargon. “Development Hell” is a Hollywood term for a project beset by any number of pre-production issues: wrangling over rights, cast changes, rewriting, legal financial issues, whatever may prevent a picture from getting made. This, our world-of-becoming, is the only world we know, and it’s a kind of hell. The train of days, eternal suffering: “you open a door / only to find / another door / and another / until you find / the people / who park / their money / in absurdity.” Craig melds Buddhist, existentialist, and anti-capitalist lines of thought: Life is suffering, existence is hell, hell is other people, and those people make their money by making worse the world.

I could quote a few more instances of this, but I don’t want to make Craig sound boring and didactic. He can be didactic, but charmingly and ironically so. Craig speaks on this very danger later in the poem: “and that’s the point / you’re left with / a vague / unreal feeling / like you haven’t / had enough / proper sleep / which these days / it’s probably true / that’s the thing / about constant / combustion / there is not much there / not much / to make / commentary on.” Anti-capitalist catastrophism has gotten to the point that William F. Buckley Jr. once remarked free-market capitalism had: “it becomes rather boring. You hear it once, you master the idea. The notion of devoting your life to it is horrifying if only because it’s so repetitious. It’s like sex.”

So we’re all fucked. So life is suffering and all that is solid melts into air. How’s a guy to catch a break? Craig has some ideas: “some parts / feel obvious / like the act / of love / is the only thing / that exists / I’m not sure / what it’s saying / yet / but it feels / something like / enjoy / the oysters / while / you can / you know / like something / terrifying / is going / to happen.” And yet: “it’s got to be better / than a big / bouncy / beach ball / embodiment / of self-love / at the arena / aligning / with your / core / values / and purpose / nirvana / is an ancient / way / of thinking / about / what’s in it / for you.” Humanoid has a lot of this jokey-earnest argumentative performance that makes staging an argument via quotation easy. Argument is another way to manage the self: “You want / to become / what you’re saying.”

Everybody’s progress through time entails innumerable everyday losses of selves and moods and desires except for the residue of memory, not an entirely voluntary or self-directed faculty. Craig notices that people like to fixate on mythically harmonious moments in the past that were actually hell to live through (the first poem is accordingly called “Harmony Myth”). One of his examples is ’90s fashion: “people are trying / to bring back / the shitty pants / but this time around / nobody’s biting.” Any moral or aesthetic progress is a matter of sheer luck; and yet sometimes Craig trips on how happy we were once and still could be: “almost all / Barry / White / records / are under / five bucks / and they are / all good / but still / they don’t / sell / well / don’t people / fuck / anymore?”

Page images provided by Joel Craig.