Jordan Davis Reviews Serge Fauchereau's Complete Fiction

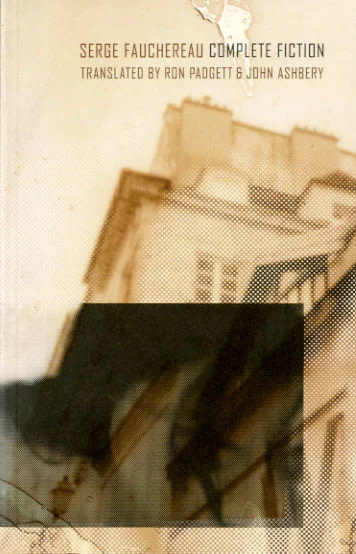

Serge Fauchereau, tr. Ron Padgett and John Ashbery

Black Square Editions, 2002

Reviewed by: Jordan Davis

March 21, 2003

// The Constant Critic Archives //

A glass of papaya juice

and back to work. My heart is in my

pocket, it is Poems by Pierre Reverdy.— “A Step Away from Them,” Frank O’Hara

One view of criticism is that, whatever its ostensible subject and purpose may be, its real task is to slip the alert reader, by means of footnotes, odd comparisons, and incidental remarks, the directions to a party that it would be better not to make too public. An underground railroad of aesthetics, or ethics, or whatever was sitting where your particular bull session on the purpose of art saw the bottle stop spinning.

I can say with some confidence that I’m not the only reader who looked into Jane Bowles because of a remark John Ashbery made, or at Henry Green because he was the subject of Ashbery’s MA thesis. And Ron Padgett was hardly the only poet to read the concluding lines of “A Step Away from Them” and feel a curiosity greater than could be satisfied by the Rexroth translation in the New Directions format that just fits in the breast pocket.

Reverdy is labeled a cubist, and while it’s debatable whether it makes any sense to apply to poetry a term that underscores the motion of attention through time across the surface of a static work—poetry always already does that!—there are family resemblances. Typographically, his poems generally compress into the frame of a single page the findings of Un Coup de Des N’Abolira Jamais du Hasard. Temperamentally, though, his poetry so full of hirondelles and glimmers is much closer to the cold sweetness of Cezanne than it is to the sum of destructions of Picasso. If you have a year of college French you can probably parse most of the sweet, sad, whispery, and rock-solid poems in Main d’Oeuvre, his collection of poems most under the spell of modern art, and least explicitly preoccupied with the Church. Most of the translations I’m aware of generally miss the point (near as I can get it), although there are a few by John Ashbery in Mary Ann Caws’s selection from 199_ that suggest what sent O’Hara into that full-stop reverie.

For years I thought Serge Fauchereau was, if not a hoax, then at least a pseudonym for some Franco-American syndicate committed to carrying on the work of the great 20th century French and American poets, but in prose. These pieces would appear in small magazines, not always the ones in which you would expect to find their translators’ names, with no indication of the provenance of the work of this sometime-professor in America, sometime curator at the Pompidou. And really, there’s no reason to doubt that there could be a secret someone writing such sentences as, “Sure, words are just words, sounds uttered in the void, little ants frozen against the whiteness, but that’s not all.” I’d have to go all the way back to the first books of poetry I felt something for not to remember that I know perfectly well how such a sensibility dedicated to light, clarity, and poignancy in the morning would not just automatically be known and adored, if there were a real person behind it.

Fauchereau is real. Or anyway, someone very much like the person I imagined writing his work read late last year at the Poetry Project, accompanied by his translators. His book opens with an epigraph from Reverdy: “Ah, the horrible temptation to know everything that is found in books when one is also a bibliophobe totally in love with what happens in real life.” There must be some readers who take for granted the calculus of maximizing both their enjoyment of life and their need for constant travel over the surface and to the interior of text: not Fauchereau. Consider the inflections of the Ozymandias-impulse in the second sentence of this book:

There exists no dimension other than time, but time in your westernized cities treats you worse than the jungle that has devoured the buildings around here, because there still remain some traces of these bronze-skinned men, although the wind passing through the crests of the temples produces no sound and the dignitaries disappear as the stucco flakes off.

Count the pleasures: he leads off with a counterintuitive assertion; he makes a claim about the reader’s well-being, including in the comparison the word “jungle” in all its active, wild force; he evokes a colonial setting with its excitement and tragically misguided energy; and he connects the often-observed effects of erosion with the often pleasant feeling of being in the wind. I’m not crazy about “stucco flakes off”—unhappy association with dandruff—but at least there’s a physical-mental sensation there that bypasses simple retinal imagery. Above all, he speaks directly and surprisingly on subjects one should be predisposed to stamp “Rilke was here” (or yes, Shelley) and consider dismissed—but it’s not possible, he’s too French to be as Francophilic as Rilke (or Shelley).

Packed in its cottony husk, a horse chestnut. Under the sheets, under the covers, it’s pleasantly warm, and the true source of warmth is that other body, beside you. Above the roundness of shoulder and the wavy air spread across the pillow, you see the window’s rectangle where day is beginning to rise. Outside, the wind makes the trees rustle, and you hear the rain, too. It’s nice, it’s warm. But beyond the shoulder, the glimmering at the window has an airport blinking in the early morning.

Not to get up on the soap box of happiness, but there is a peculiarly French gift for appreciating sensuousness on display here, tempered with an American realism that, when it’s Padgett’s, anyway, doesn’t slide over into real misery, only the recognition that “You have to get up, go, and pick up living like a man again.”

Fauchereau’s work bears an uncanny similarity to that of his translators. A four-page meditation on the border ballad “Chevy Chase” digresses to a parking accident in a lot at “the Chevy Chase Residence,” about which the narrator parenthetically wonders, “Maybe it was called that because of the nearby Chevy Chase National Bank,” with stops along the way to consider Eubie Blake, Wyatt Earp, and the outcome of the turf war at the heart of the ballad. You don’t have to be in possession of the entire Padgett corpus to recognize Fauchereau’s preoccupations are, well, felicitously aligned with his own.

Translators often refract their source texts with the light they themselves give off, and Padgett and Ashbery, two of the finest poet-translators of our time, are all the better for the liberty. Ashbery goes so far as to translate what I imagine was “mon vieux” as “old buddy” in his characteristically Olympian-avuncular style (“no more juice in the electric guitar, old buddy”).

Fans of W.G. Sebald’s luminous and poignant German anglicisms may or may not catch on. I understand that this collection is only a tiny sliver of Fauchereau’s translated output. I hope this is not the last time we see these three writers in one volume.

COMMENTS:

None.