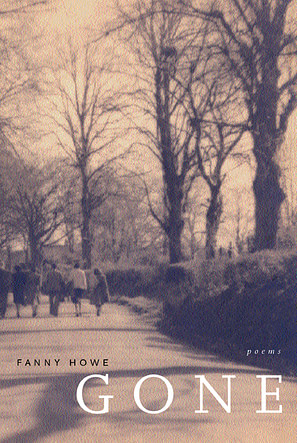

Joyelle McSweeney Reviews Fanny Howe's Gone

Fanny Howe

University of California Press, 2003

Reviewed by: Joyelle McSweeney

July 30, 2003

// The Constant Critic Archive //

Fanny Howe’s Gone reads like a soul’s travelogue in installments, a turning over of themes, positions, and bodies as the author seeks, as Simone Weil did, to maintain a conversion through effort. The single prose poem of the book, flatly titled ‘Doubt,’ confirms this alliance, both in its notebook style and in its seemingly self-reflective analysis of Weil’s project:

Her prose itself is tense with effort. After all, to convert by choice (that is, without a blast of revelation or a personal disaster) requires that you shift the names for things, and force a new language out of your mind onto the page.

Issuing from a lesser poet, a statement of theme like this might collapse the possibilities of the volume around it; from Howe, this clearing of the mental air allows the lyrics of this volume to escape from the duties of exposition and reveal their true identities as the most efficient, immediate, and consistently dazzling short poems of recent years.

Here, for example, is exactly one half of the poem, ‘Some Day’:

Some day a sheep with green eyes will meet me

at a door“self, come in

and be as vigilant

as the alien you are.”I will enter with a book in my hand, I’m sure

For totemicness, simplicity, and breathtaking oddness of statement and address, this is a poem to stand beside Blake’s Songs of Innocence. Yet it is not a poem of complete innocence, as the insight about the self’s alien vigilance and the experienced “I’m sure” suggest. Instead of an overt rhyme scheme, here is a buried system of half-end rhymes—door, are, sure—which punctuate complete thoughts and create a gently musical substructure that pleases and ensnares the adult ear. The half-end rhyme and the admixture of naiveté and irony are Howe’s ready tools throughout Gone.

One would be remiss not to stress that these short poems are parts of larger meditative structures. The above poem is one in a grouping called ‘The Descent,’ which apparently captures short glimpses of the soul in its stays at various addresses, including prior to and/or after life on earth. The first long grouping of the book, ‘The Splinter,’ shows the soul in the process of birthing itself through childhood awakening, or separation from the mother, or differentiation from corporeal self. “(Skin is what I she and they see when we see feelings)” is a not untypical line from this section, but equally common are passages like these:

So the first shall be lost

and the zero before itand the weight of faithless skin

shall thicken its authorityin a mind fired by a spark

whose intake of breath is automatic

until it isn’t

Here the eschatological misquote of the first line (‘lost’ for ‘last’) allows a splinter of the mundane to enter the poem, for what could be more mundane than error? This bit of psychology then permits the manmade mathematical imagery of the second line and the anatomical imagery of the final couplet. At the same time, the rhyme of “before it” and “authority” is marred by the latter’s daughterly “y,” and the missing end rhyme in the second half of the poem turns up as a sight-rhyme between “authority” and “automatic.” In this massive seven-line poem, mundanity enters and fractures theology, but makes it truer to (human) life.

The bulkiest section of the book, ‘The Passion,’ is an erratically violent, erotic affair, introducing a Christ-like ‘he’ into the proceedings. This section delivers many surprising reprises of and departures from the Passion story. In the Catholic Passion, Christ is the star of each scene, but Howe’s version gloriously breaks this rule. At one point, the speaker’s longing for this absent figure allows her to play his role and conjure up a quite remarkable universe all her own. Here’s that installation in its entirety:

Come back

to three lines of light on a little river—

one pink, one green and one aluminum—

come back to being.

This delicate vivacity is present elsewhere in Gone, in poems not circumscribed by the weight of ‘The Passion.’ ‘The Source’ relates a time imaginatively predating the struggle recorded elsewhere in the book. It begins thus:

The source

I thought was Arcticthe good Platonic

Up the pole

was soaked filman electric elevation

onto a fishy platform.

Here is all the wiggly, fishtailing delight in the materiality of language that is the hallmark of contemporary poetry, with none of its aimlessness; Howe’s language attends a motion upwards, toward

. . . a light that powered out

my ego or my heart

before ending with a letter.

Again, that simplest of tools, enjambment, permits crushing surprises.

Apart from its meditative heft and the knockout grandeur of individual poems, Howe also fulfills that most antiquated measure of a poet’s worth: she provides memorable lines. Striking among these are “your soul is just a length of baby,” and “Heart, come along and be as heartless / as you know you are.” It is this line-by-line excellence that places Howe in the forefront of American poetry. She wrestles us off our asses and into grace.

COMMENTS:

Fanny Howe August 8, 2003 at 9:36 am

Dear Joyelle, Thank you so much for your time and your thoughts. I find them really helpful to me, and wonderfully stated.

Fanny

Michael Catherwood October 8, 2003 at 8:05 pm

The attempt at contrary abstractions seems formulaic and robotic in the following:

So the first shall be lost

and the zero before it

and the weight of faithless skin

shall thicken its authority

in a mind fired by a spark

whose intake of breath is automatic

until it isn’t

So if I were to re write this poem in its opposites, it might go like this:

But the last cannot be found

and the infinity preceding it

and the vacuum of religious bone

cannot empty its slavery

out of a soul collapsed by entropy

which exhales sand in fits and starts

continuous throughout

This took four minutes. I’m not sure, but I certainly wanted more backfire from both poems.