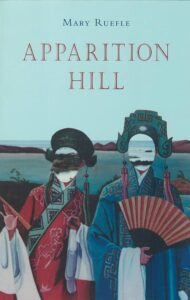

Jordan Davis Reviews Mary Ruefle's Apparition Hill

Mary Ruefle

CavanKerry Press, 2003

Reviewed by: Jordan Davis

November 2, 2003

// The Constant Critic Archive //

Mary Ruefle’s poetry has always preferred to be read at twilight, when what appears at first to be a tissue of wryly-observed but loosely related details can become in an instant as solid as a gravestone (or as weird as an illness). Generally, her poems begin with unassuming observations, but more and more she’ll state, as in “Nota Bene” from 2002’s Among the Musk-Ox People: “Once an octopus, always an octopus.” Her facility for bizarre propositions is generally evenly matched with her capacity to induce the reader to deny that anything unusual is happening.

The stamens of the lily stiffen into claws.

Gentle lily!

The lily begins to eat us all.

When two angels met in a closed room

was there not a lily on the table between them

and did not the lily on the table between them

have a hunger sent from God?

(“Against the Sky,” Among the Musk-Ox People)

She does not obfuscate by changing the subject, or by growing vague. She baffles, by escalating her assault on reason, often with an exclamation or mediating mild praise, never for a moment conceding that she might be making only some sense.

Her recent decision to develop a command of hilarious archaic vocabulary reaches back to Marianne Moore, parallels Charles North, and echoes forward to Chris Edgar: “Some minor foxing in the clouds went / unremarked… No one was bastinadoed” (“Derby,” Post Meridian). In “Pressed for Details,” from this same 2000 collection, Ruefle sketches her affinity with the stories of Robert Walser (“you could say / I fell in love with a dead man”): “Most respectful sir: Walser wrote this curious form of address / brings the assurance the writer confronts you quite coldly.”

The endings of some of her poems are so good they betray an unseemly concern with devastating the reader, running up the score in the final seconds: “when I die there’s always the chance / someone with nice hands will wash me”; “Children like this game because it is simple, / adults because it is sad”; “Let their daughters keep the diaries, / careful descriptions of boys in the dark.” For a while her lesser endings could be accused of recalling James Wright aping Rene Rilke, but that moment in her work (as in the poetic culture at large) seems to have passed.

Apparition Hill is her most recent, her seventh, book. The manuscript dates from a 1989 sojourn teaching in China, and therefore it collects poems written in advance of Cold Pluto. These jolly poems about disappointment, irrelevance, and peripheral experiences give the willing reader a feeling not unlike that delivered by a tumbler of armagnac.

My mother took her squirrel stole

out of its bag and I saw her initials

on the inside satin shimmering

like the future itself.

My father took his golf clubs out of their mitts

and I saw the enormous integers

each one was assigned.

(“Cul-De-Sac,” Apparition Hill)

I like unruly combinations of words such as “enormous integers” when I come across them in narratives such as this, where the language gives the appearance of having been only lightly torqued. For example, stole looks enough like a verb in the past tense without took preceding it. Two lines later, the line break and the imperceptibly brief memory of having to work to parse stole as a noun conspire to make it sound like her mother’s monogram appeared on some mysterious gerund shimmering. The next line, this tangible luster is ushered back from the land of the objects, but the reader lags behind in the emotional world of someone’s early autobiography, where giant numbers emerge menacingly, like hands, from gloves.

I suppose I’d get some charge from nearly any mention of outsize numerals, but lock me up for a pathos addict (or just dose me), I enjoy how they make me feel here; clearly the author does too, even if she insists on observing that “these things are fleshless and void, / as unimportant as a mouse,” and “My mother’s name and my father’s numbers / lie in a landfill that is leveled far away.” “Cul-De-Sac” emerges as not just an autobiography, but a story told to an estranged brother with “a van full of rifles, / a string of wives and children / along the interstate, and I do not know / if he shaves or does not.” I don’t ordinarily care much for luminously bleak objective correlatives, but since the poem’s speaker acknowledges that her brother likely has a matching set worked out for her, I relax, knowing that symptoms aren’t going unrecognized: “We each think / the other has flattened a life.” The poem closes with an apology that doubles as the return of the voided details she ambivalently repressed earlier in the poem: “Brother, I have been unable to attain a balance / between important and unimportant things.” If that isn’t an agree-to-disagree, a dead-end with a u-turn, then just dose me.

If hers is sometimes a literary, knowing poetry, she gives it bite. In “Diary of Action and Repose,” she destabilizes an already non-standard nature scene (bullfrogs inflate in “some small sub-station of the universe”; the speaker can smell jasmine—being fertilized, that is, and an unseen flute player isn’t setting a contemplative mood, but rather, “asserts his identity / in a very sweet way”) with the quip, “I’ll throw in the fact it’s April in China.” But in “Dove,” Ruefle alludes to the Asian writer her particular mix of sarcasm and the sublime most recalls, and it’s not a Tang poet:

One thousand years ago a woman in Japan

with no name

wrote a book without a title.

I can turn the pages

I can rip them out

and fold them,

put them in my pocket

and walk into town. She said

even at the best of times

I am not much good at poetry

and at a moment like this

I feel quite incapable of expressing myself.

“I like to read because / it kills me,” Ruefle writes, “I like it dull.” She writes of students rejecting Joyce’s “The Dead”: “it’s puerile, that’s what it is.”

Ultimately, this is a poetry that craves, pursues, and secures the extra—the roux, the crema, the patina—that indicates the presence of beauty. If these indicators themselves evanesce all too quickly, so it goes with all gestures of approval. And yet Ruefle continues to cope with the bombardment of sensations, though they pose a constant physical threat to her wellbeing, as she explains in “Funny Story”:

What if the moon, awash as it was

in decanted light, was dangerously close

to disappearing altogether

and for good this time?

So I just stood there.

I let it take my breath away.

That’s OK I said

take my breath away.

And it was gone.

COMMENTS:

Janaka Stucky November 3, 2003 at 4:54 pm

Despite moments of marginal academic elitism (“her lesser endings could be accused of recalling James Wright aping Rene Rilke”), Jordan Davis’ review of Mary Ruefle’s Apparition Hill was eloquent and insightful. It takes a nimble critic to do justice to Ruefle’s individual voice, and I think that Mr. Davis did a remarkable job communicating both the nuances and the boldness of her work.

Thank you for this review. If it leads more people to the pages of Mary Ruefle’s poetry, you have performed a great service for contemporary readership.

Richard Taylor December 7, 2003 at 9:29 pm

A good review – I hadn’t heard of this poet. Seems she has some of the quirkiness (I mean that in a good sense) of some of the more interesting English poets. Richard

C.M. Mayo December 8, 2003 at 10:45 am

Hi, I just received this for the first time, and it looks wonderful. I edit Tameme, a bilingual journal that features prose and lots of poetry. Where might I send a review copy? Saludos and good wishes.

The Editor Replies:

Dear Publishers: Please note that The Constant Critic reviews only books of poetry; not journals or chapbooks. Herewith please find the Critics addresses, to which to send your review copies:

Jordan Davis

1793 Riverside Dr., #3B

NY NY 10034

Joyelle McSweeney

1928 8th St, Apt. B-1

Drury Lane Apts

Tuscaloosa, AL 35401

Raymond McDaniel

309 4th Street

Ann Arbor, MI 48103

Michael Catherwood December 8, 2003 at 6:43 pm

Very nice review. As the poems go, I’m a little leery spending money on poems that end by reverting back to the speaker. It’s hard for me to watch poets watching themselves; no matter how graceful the language, a poet gazing into his or her navel somehow disturbs the universe for me.

Ginsberg’s White Shroud struck me the same way. Many poems knocked my hat off, until confessional itch was scratched, often leaving me feel used.

This is personal taste though, and the review is nicely written and does what it is supposed to do, let me decide.