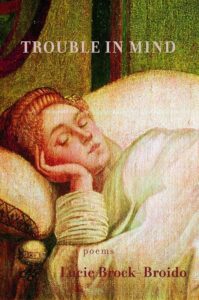

Ray McDaniel Reviews Trouble in Mind by Lucie Brock-Broido

Lucie Brock-Broido

Alfred A. Knopf, 2004

Reviewed by: Ray McDaniel

February 16, 2004

// The Constant Critic Archive //

The abuse of one’s talent: To whatever degree such a thing is possible, we judge the act harshly. Whenever I hear tell of an Artist Who Has Abused His or Her Talent, I picture one of those little Keebler elves, bent over a cauldron, manipulating chocolate via elven magic, contriving chocolate that will then go forth to, oh, I don’t know . . . turn to alum in the mouths of trick-or-treating innocents? Something evil.

I think it more likely and more common that our talents abuse us: In this imagining, I recollect those old Warner Brothers cartoons in which the diminutive characters prove unexpectedly puissant: The chicken hawk smashes the rooster, first slamming him to his right, and then his left, and then to his right, all the while betraying not a jot of effort or even interest.

I offer this distinction between talent well-spent and talent on a spending spree of its own to clarify my mightily mixed feelings about Lucie Brock-Broido’s Trouble in Mind, which poses a number of problems, for all that it poses them prettily. And I illustrate the distinction with Keebler elves and Looney Toons because these are the kinds of things absent from Brock-Broido’s poetry: Her worlds lack the texture of the manifestly quotidian. Processed food products do not defile the Broidoverse, and while I have absolutely no objection to this absence per se, these types of absences, this abdication of internal compass or contrast, begins to leech something vital from Trouble in Mind. The book presents a dilemma: a set of perfectly distinct properties which somehow become indistinguishable.

Brock-Broido’s poems are, even at their least and slightest, remarkably fertile—the musicianship of her language is such that even apparently careless constructions constitute true beauty. This beauty, however, can both happily and unhappily obscure the consequence of her perhaps haphazard choices. Brock-Broido suffers from a version of Midas’s gift: all language blooms under her attention, but the blooming thereby made so overgrows the poems themselves that the shape of the garden beneath becomes lost. We do not need to distinguish between garden and jungle to appreciate the scent and texture of full flora, but such confusion obscures indiscriminately—archaic or facile barriers disappear, but so do poetic distinctions within the poems themselves. This book thus creates a hothouse closeness, but without the reciprocity of exchange—whether you read it as a superabundance of oxygen or of carbon dioxide, the book is chemically imbalanced. Something in the mix proves unnervingly and claustrophobically out of whack.

In other words, I loved the language of Trouble in Mind without having much memory of the actual poems in which that language is cast. Its omnidirectional variousness—its nothingness by way of its myriad individual somethingnesses—casts Brock-Broido’s The Master Letters in an ironic light. Many complained that Letters so exaggerated its own density that it became indigestible; readers were heard to claim that they had to read the poems again and again before any measure of meaning revealed itself. I recognize that density, but never thought of it as a problem—there was something deeply satisfying about poems thick enough to require effort to fully savor. These poems were layered, not obscure. Some resisted that weave, but Trouble in Mind now indicates that texture may be the means by which Brock-Broido achieves the equivalent of structure. In its absence, petals of her language unfold to wonder, but sometimes fail to describe or induce unities.

I’m going to rely on the book-object itself, not just the poetry but the prose descriptive of the project and the poet, to supply the means by which to discuss this poetry. Now, God help those unfortunates upon whom falls the task of writing the jacket copy, but there’s something about this copy that hints at the difficulties Trouble in Mind engenders:

“With Trouble in Mind, her long-awaited third collection, Lucie Brock-Broido has written her most exceptional poems to date. There is a new clarity to her work, a disquieting transparency, even in the midst of wild thickets of language for which she is known.”

A “new” clarity! To what does this refer, save the reader’s fear that this book will ask of them the same labor Letters did? And what in particular about her transparency disquiets, and how does transparency manifest in the midst of “wild thickets”?

Well, Trouble in Mind does provide poems that apply a classical self-containment:

Herculaneum

No one is bored, just barbaric

Anymore. Ash admixed with rain, which cooledThe air. How much longer will this beauty

Of yours last?As if even the idea of the city

Has been lost for twenty centuries.Don’t quail like this; go

Gracefully instead.

Eros entersThe room like a lesser god stopped still

In the middle of a bath of oil & umbrage inThe exquisite hour.

No one is

Exquisite anymore. The river is so small nowIt will be hard to drown

In it. And still this world’s a pretty one.What world.

Okay, transparent, fine—a good poem, but also conspicuously thicket-free.

“A poet ‘at the border of her own allegory,’ Brock-Broido searches for a lexicon adequate to the extremities of experience—a quest that is as capricious as it is uncompromising. In ‘Pamphlet on Ravening’ she recalls, ‘I was a hunger artist once, as well. / My bones had shone. / I had had rapture on my side.’”

Of what use is this? Such a description suggests that the poet herself, her own extremities of experience, describe the primary font of the poetry’s power. Such a claim, specious as it, does not profit from the lines quoted: hunger artist, bones, rapture—these are affectations, the poetic tokens of someone who eats ether and shits silk, and they do not fairly represent either the poem cited or the poet’s work. So what, you might ask, it’s just the jacket copy. But the problem is that certain elements of the poetry could lead the reader to imagine such faery fantasticals. Consider the following samples, plucked from context but meant to communicate the degree and intensity of such affectation:

And I, the mother of nothing, mother / Of nothing at all

The improbable thoracic cavity of me

My medieval / Universe where love lies / Over the law

All-bearing / Nature was my fictive frame

He had an empty cloakroom / In the chest of him.

You will find me then, / A little damp, in / My small Madrid of shame

My torso is a cedar chest I the brief closet / Of the middle of a

country, hollowWhen she died, it might as well have spooned the quince- / Shaped heart from me.

I do not want to be a chrysalis again.

I was turning over the tincture of things

Now, in each of the poems from which these are drawn, one can also find fabulous riches of association and music. No one poem is so subject to affectation that it induces a wince as might the lines quoted above. So what are these lines doing? How do they maintain against the likes of “Still Life with Feral Horse”—

It is love and its relinquish

I am discussing here,

A sorrel horse loosedOn a salt marsh island

Pelted by high storms,

And furious. He will notBe handled by human

Hands, not in this given life

Of gratitude and tallow lampsAnd famous churlishness

I have heard tell

That you know how

To kill a man.

Or “Another Night in Khartoum”—

A sack of bees

Like a cataract

Opens, tangling its skein, filling the roomWith the heavy machinery

Of honey and anatomies, and light.Now the old silt

And the waterwheel of work, in cools of cave,On further shore.

When the potter wasps gather

In their nests of clay, they will make a noiseInconstant as the White Nile

Where it meets the Blue oneIn the ruined evening of Khartoum,

Where a king’s mouth fills with

Cowered weeds.It is not enough to have

The very thing you loveJust for an attendant while, not even in that place

Where you could not stand

To be civilized.

“The book is laced with sequences: haunted, odd self-portraits, a succession of poems provoked by discarded titles by Wallace Stevens; an intermittent series of fractured and beguiling lyrics that she variously refers to as fragments, leaflets and apologues.”

That list of items on the other side of that colon: they aren’t sequences, because sequence mandates order, and these collections—as delightful as they sometimes are—largely deny order in that they privilege no one idiom, approach, placement, or tone over another. Hooray for catholicity, but descriptive inaccuracy here corresponds to an anxiety of the book entire, which is that it reads like an assemblage of a lyrical genius’s poetic fragments. The undisputed brilliance of the language does not justify the diffidence of the assembly, nor does such diffidence require justification, if the poems act more lucidly on their associative instincts. As a reader, I won’t seek structural meaning unless the poems ask me to; many of these poems seem to ask this of us without really betraying much of an inclination to reward the request. Regard “Leaflet on Wooing” —

Wanting is reposed and plump

As the hands of a Romanov childFolded in the doeskin sashes of her lap,

Paused before the little war begins.This one will be guttural, this war.

How is it possible to still be startledAs I am by the oblong silhouette of the coiling

Index finger of a pending death.No longer will

Wooing be the wondrousThing; instead, a homely domesticity, constant

As a field of early rye and yarrow-lightWhat one is fit to stand is not what one is

Given, necessarily, and not this night.

“Wooing” contains a phalanx of gestures. The poem need not arrange them to achieve neatly sewn meaning, nor need the poem decrement to the suggestiveness of loose mosaic style. But I cannot help but think that the weakness of this poem derives from Brock-Broido’s movement away from “density”: the savories of the poem sit in a pot, neither strategically arranged nor transformed to soup or stew. Where once Brock-Broido depended on sheer weight of language to heat and alchemize her poems, this newfound “transparency” reveals the language as too often abandoned.

“Trouble in Mind is a book that astonishes us afresh at the agility and the uncanny will of language, which Brock-Broido is not afraid to follow where it may lead her: ‘That the name of bliss is only in the diminishing / (As far as possible) of pain. That I had quit / The velvet cult of it, / Yet trouble came.’ Even trouble, in Brock-Broido’s idiom, becomes something resplendent.”

There is much here that astonishes, and earns its keep though force of imagination. But the “uncanny will” of language must be met with some mode of deliberation, of discipline; the poet must marshal its agility to maintain motion, lest the undirected grace of the language lose focus. Reading Trouble in Mind sometimes feels like watching a gazelle trip; one can marvel at the animal’s power and posture, while simultaneously wishing it greater coordination. I agree that Brock-Broido will follow language where it will lead her; I just wish she would lead it in turn. And that trouble become resplendent means little if all features acquire equal resplendence; such glimmer and life becomes dim indeed when the poet will not decide to what light her talent best be turned.

COMMENTS:

Daniela Gioseffi February 19, 2004 at 12:28 am

I agree with Ray McDaniel’s estimation of Lucy Brock-Broido’s poems in Trouble in Mind, and he expresses his opinion with sensitive and intelligent prose.

Too many of our contemporary poets speak in the code language of unusual imagery and flamboyant metaphor and simile, often beautiful in itself, but without ever bringing the poem home to mind-–to a poetic sense, to a “meaning,” a purpose.

I’ve always felt that a poem can’t just be, it has to “mean” as it has to “just be,” and I don’t imply a clumsy, prosaic hit-you-in-the-face sort of “meaning,” but a sense of shared experience, a sense that the reader is brought to with grace and subtlety.

Brock-Broido seems more in love with her own pirotechniques, and ability to dream up new imagery, more than with really sharing experience with the reader. She dances alone saying “look at me move” in many of her poems.

There’s far too much solipcism in much of contemporary poetry, and Ray McDaniel is gentle in his truthful well-wrought critique. She is talented without a doubt, but abusing her talent.

Sincerely,

Daniela Gioseffi, widely published reviewer, poet,

critic, Member of the NBCC

Debbie Urbanski February 20, 2004 at 9:36 am

While it’s fine to critique and dislike Trouble in Mind, I find it rather ridiculous and not at all useful to be critiquing the jacket copy/PR of the book at the same time, considering Brock-Broido penned the poems, not the jacket copy. Arguing with the marketing spin for a book– rather than solely with the poems themselves–is like arguing with a straw dummy, and seemed misplaced energy to me. Ray McDaniel does write “I’m going to rely on the book-object itself, not just the poetry but the prose descriptive of the project and the poet, to supply the means by which to discuss this poetry”—but my question is why? I think McDaniel’s reasoning for having his argument based in opposition to the jacket copy should have been included in the review.

Jeffr– Julli– February 20, 2004 at 10:32 am

In your wittily demotic “eats ether/sh-ts silk” objection, I think you ask something unrealistic of poetic personhood: realism.

Your underlying premise: poetic language should correspond to a mundane sense of identity, a lumpen-ego that you presume to be shared by all Everymen; it should not fabricate grandiosities of self that lie outside mandatorily ordinary universality.

You miss, though, the true lesson of your Looney Tunes. The marvel of cartoon characters is not that they go out of scale (“diminutive . . . prove . . . puissant”), but that an animated drawing comes to possess ~any~ illusion of personality whatsoever, no matter how pipsqueak. Most importantly, that illusory Warner Bros. personality is always stilted, exaggerated, and synthetic, and never of the same commonplace common denominator that other media, and some critics, ask all portrayal to stay weighted at.

You’re mistaking personhood in poetry for the sort that results from more or less direct speech-to-page prose transcription, under the most normalizing restrictions, as in diaries or e-journalism, and asking for the potentials of a poetic ego ~that is always~ trompe l’oeil pseudo-ego in the first place to be narrowed to an unintimidating average. . . Which forecloses the possibility that “My torso is a cedar chest,”—like the other lines you quote, so stridently Dickinsonian—might not ~be~ the approximate signifier (objective correlative) for an actual sense of self simply other than your own. We don’t all have one-size-fits-all private interiorities.

Have you no wooden peg leg?

In a man, her gestures toward self-caricature would be ~femme:~ the reason you’re not hearing her ~accuracy~ is that she’s writing a paradoxically mannerist ~ecriture feminine,~ —while you’re thinking rooster-bashing.

The ~content~ of the lines you’re wincing at: motherhood; uterine imagery, —however upward displaced on the anatomy (“thoracic cavity,” the “cedar chest,” the heart-excoriated chest, a chrysalis) or Freudianized onto empty cloakrooms, and unmentionable girlesque ~dampnesses.~

(And I thought “chicken hawk” meant “Welcome to Neverland”!)

In opposition to her “affectation,” what is there to put in fiction’s place? The ~naturalistic?~ The documentarian?

Self, a construction in the first place, is all the more manifestly a pure ~invention~ in poetry; then, the excess you’re accusing Brock-Broido of is just an upper limit of a kind of weightlessness that, like stratosphere inside mesosphere inside thermosphere, ~has~ no lower limit.

How Brock-Broido blundered, too lacy. Ray McDaniel: There should be roofs on castles in the air.

Jo Sarzotti February 22, 2004 at 6:54 pm

Lucie Brock-Broido does not need me or anyone to defend her remarkable work in Trouble in Mind, but the weird wit of McDaniel’s review draws me into the debate, as do the issues of “clarity” and “density” — I won’t comment on his using the jacket copy to hinge his critique as it appears merely practical, if a little desperate. He takes the posture of a disappointed fan of Brock-Broido’s who regrets that the new work lacks the density of Master Letters and that its language is “undirected.” He observes that other readers, unlike himself, “resisted” the dense layers of Letters, and I now suggest that McDaniel may himself be resisting something else in the new poems, which is a closer-to-the-bone revelation of the speaker’s feelings. For example,

“I had hoped for, all that Serengeti / Year, a hopelessness of less despair / Than hope itself.” Or, “I adored you as much as an aluminum / Bucket of storm after / A great unlovely silvered thirst. How / Nice for me.” Or, “I am tired / Of women who are sad. I am tired / Of men who are tired.” Or, “I can say ‘little’ / now as many times as I goddamn / Want, here in the hour of my forty years & four, / Here beneath the hard back hour of my death or / Past as it will really happen here . . . “

I pick these lines almost at random, and notice that their tone comprises the “structure” McDaniel complains is absent throughout. The book’s poems are, in fact, “structured” by a voice, by a “clarity,” which exposes much more than in Brock-Broido’s previous work, her being quit, as she would say, of the apparatus of different personae. We still revel in her exotic, romantic, archaic language (which McDaniel praises), but there is also a more refined density in the new work. We are invited into a different though recognizable universe (“Broidoverse” in McDaniel’s truly inspired locution) but enter at our own peril—this is a world where in spite of beauty and accomplishment, one can still feel naked, like Lear’s “poor, bare forked animal,” who recognizes that hope holds more despair than hopelessness. Trouble in Mind is not ethereal, and it is very clear:

“By November, the tines of my deepest thoughts will be “in / Velvet.” And I, the mother of nothing, mother / Of nothing at all, will spook, be / Loving still, but just the same, the same.” (“The Deerhunting”)

I think that rather than complaining that Brock-Broido’s new book is not like the old, we should give ourselves to her new work with as much courage as she shows in writing it.

Joan Houlihan February 23, 2004 at 7:06 pm

“The abuse of one’s talent: To whatever degree such a thing is possible, we judge the act harshly.”

This puzzling, statement implies that Lucie Brock-Broido has abused her talent. But what does that mean? This, along with other of the reviewer’s innuendoes, is not only never explained or defended, it’s not even really stated. This sentence seems to say only that it may be possible to abuse one’s talent–and it may not. If it is possible, then “we judge the act harshly” (however such an act is defined–it is never defined here). If it’s not possible to abuse one’s talent, then we don’t judge the act harshly, I guess. What has been said here? It’s difficult to go on reading such a newspeak-y, you-can’t-pin-me-down, start to a book review, but curiosity pulls me onward…

“Whenever I hear tell of an Artist Who Has Abused His or Her Talent, I picture one of those little Keebler elves, bent over a cauldron, manipulating chocolate via elven magic, contriving chocolate that will then go forth to, oh, I don’t know . . . turn to alum in the mouths of trick-or-treating innocents? Something evil.”

Nothing about the book or author, no statement of opinion to defend or elucidate, but an “imagining”, seemingly postioned here for the audience’s admiration/amusement, a little meandering of the reviewer’s fantasies about what a phrase might mean IF it were true–or even possible “to whatever degree.”

“I think it more likely and more common that our talents abuse us: “

They do? Is it because we abused them, or are they just ornery?

“In this imagining, I recollect those old Warner Brothers cartoons in which the diminutive characters prove unexpectedly puissant: The chicken hawk smashes the rooster, first slamming him to his right, and then his left, and then to his right, all the while betraying not a jot of effort or even interest.”

In this imagining, I see a reviewer churning out senseless, silly prose while an editor who has pricked her finger sleeps in a bed of hay attended by Keebler elves…

“I offer this distinction between talent well-spent and talent on a spending spree of its own.. “

What is talent “on a spending spree of its own?” What is talent “well-spent”? What is the point here? Is this reviewer saying Lucie Brock-Broido is a rooster abuser?

“…to clarify my mightily mixed feelings about Lucie Brock-Broido’s Trouble in Mind, which poses a number of problems, for all that it poses them prettily.”

Note to reviewer: please clarify mightily mixed feelings before setting pen to paper. End of note.

“And I illustrate the distinction with Keebler elves and Looney Toons because these are the kinds of things absent from Brock-Broido’s poetry: “

I see. So the distinction between talent well spent and talent on a spending spree you illustrated is… what now? The Keebler elves represent talent well-spent? Or are they representative of talent on a spending spree? Is the rooster abusing his talent in the form of a chicken hawk… or is the chicken hawk on a spending spree… or… why am I reading this? Oh, right. I wanted to find out what this reviewer thinks of the new Brock-Broido book. So far, he doesn’t. Think, I mean. He “imagines.” That’s what they like to call thinking here at Fence, where I’ve seen some of the worst minds of my generation go raving through barnyards, smashing roosters and bent over a cauldron vomiting alum.

“Her worlds lack the texture of the manifestly quotidian.

Processed food products do not defile the Broidoverse,”

Nor thoughts defile the McDanielverse.

“and while I have absolutely no objection to this absence per se, “

Good, because the absence of processed food products is rampant in contemporary poetry.

“these types of absences,..”

The absence, not of processed food products themselves, but of their type of absence…

“this abdication of internal compass or contrast, begins to leech something vital from Trouble in Mind.”

An abdication leeching at something vital is a horrible sight to see, be it abdication of internal compass OR of internal contrast (these are basically two opposites, I guess–east/west vs. dark/light… or… ? Hark! Is that an abdication leeching in the distance?

“Brock-Broido’s poems are, even at their least and slightest, remarkably fertile—the musicianship of her language is such that even apparently careless constructions constitute true beauty. This beauty, however, can both happily and unhappily obscure the consequence of her perhaps haphazard choices. “

At last, a clear statement. Reviewer–take a note: this is where your review begins, where you’ve made a statement that clearly expresses an actual thought. Does this new trend show any signs of continuing? Or does it die a-borning? I will read on as soon as I have another block of time to devote to piecing together the unedited scrambles of someone’s “imaginings” presented as a book review.

ashley wilkes February 25, 2004 at 1:49 pm

I’m not responding to the Brock-Broido review. I’m responding to Joan and her earlier, infamous essays which spun around similar issues seen here. Joan, you need Fence and all those other hateful literary magazines you cite like a drowning person needs a rope. As Nietzsche realized a long time ago, we need our enemies in order to validate our own opinions.

Bill Knott remarked awhile back that you’re just the unfortunate straw-person for the avant-crowd (what- and whoever that is) to pick on, noting these same people have propped you up to take potshots at you. I guess Bill must have missed your seven essays that you propped up all by yourself.

I’m writing because I’m so tired of your sham of a pointed-to reality, and this related pose of the sarcastic, attack-dog critic (the mien of fierceness meant to put-off comments on, here, your comments). The realism you are arguing for is the realism principled on economic transactions. “Here is a dollar.” One might ask: “Or is it?” It’s the same place where one can bask in the false charm of the Image. The Image being that holy font of Advertising, the controlling fiction of much contemporary life, which Advertising narrows in order to sell us the reduced world according to its making.

Are there no worlds beyond the fiction of syntax, of the mind apart from syntax, of the words within words, of the emotions, the combined emotions and thoughts that inveigle one to utter contradictions at a fairly regular pace? Are there no worlds that don’t conjoin nicely with the market? Are the selves/self (take your pick) just imprisoned to refer back to this fake world, a wo/man-made world of money? Or can the self/selves auger further, into and/or away from this which is or isn’t vibrating and/or dying?

I wish I could say that I am amazed at your stance on the meaninglessness of much contemporary writing. But I’m not. It’s as commonplace as breathing. The obvious test, of course, given the absurd certainty of your beloved reality (there is only one, after all) is: might one do the same for your poetry. Yours, which, I presume, you think is full of meaning:

Let’s take a look at such a heartwarming piece of dried-up, unfound, Easter candy as this uneventful (yet published!, [must be good] ) poem of yours. I have decided to emulate your tone and your earnest rummaging for meaning. I will be asking in brackets:

Reconstructing Easter [is this a girl’s name, a broken fort, or a directional?]

We [who are We?, does this include me looking in?—I’m confused] convene here [where are you, on the page here, or just where is here?], listen to Uncle B [an uncle to whom?]

in his [Uncle B’s or some other male’s] backward-pointing baseball cap [how does a cap point exactly?] [backward to whom?] lit with stories [the baseball cap is lit with stories?, 60 or 100 watt?, or are you speaking of lit/erature with stories, levels?, or what exactly?], muttering of loss [this is what you’ve come up with? how many people have said this before you?]—

a low and meaningless animal sound [as if the clich

Cheri Hickman February 26, 2004 at 4:56 pm

First, and only because I sense Joan’s invective calls for a world of disclaimers, a little context: I know Raymond; we aren’t always in agreement; and I admire his intentions & his broad intelligence. Furthermore, unlike Joan, I’m not an apologist for any particular embattled poetry movement in these our latest boring balkanized literary wars, and I’m far more interested in a fully realized collection of poems than the latest rush to defend or assert the decline or assent of such&such a school. For these & other reasons, I feel compelled to address both the content & tone of Joan’s letter.

If I’m reading Joan’s letter correctly (and generously), she’s not got a problem with Raymond’s critical or interpretative approach to Lucie’s latest collection, but rather she’s editorially hostile toward some of Raymond’s sentences? She expects his points to simultaneously contain their subpoints? She thinks the review should have started somewhere other than the beginning? Joan mocks isolated sentences, but doesn’t address the concerns, perspectives, or arguments built via those sentences throughout the text? The statements she childishly & irrationally autopsies are, in fact, fully developed in the body of the review. She’s pointing — and that’s always been rude here—which is not the same thing as thinking. I suggest she take a gander at the other letters to get a better sense of how that’s done.

Still, I suspect Joan knows this, ignores this, and so wastes our time & conceals her true objections. I can’t see that she even tangled with Raymond’s ideas, much less recognized or refuted them. I read a world of presumption, pretense, & vindictiveness in her letter. So what exactly is she scolding him for? I hardly think his little review had kerosene enough for her alarm. I suspect Joan is using Raymond’s review to defend something he hasn’t attacked. Shadowboxing it’s called. Gaslighting also comes to mind. I’m merely stating the obvious when I suggest that Joan’s letter lacks fertility, integrity, and any vital commitment to the review’s content or even to Lucie’s work, and that’s something you simply cannot say about Raymond — whether or not you disagree with him.

And here I’d like to reintroduce the possibility of legitimacy & restore an honest dialogue with Raymond’s review. I think he initiated a very relevant investigation of language & its purposes within Trouble in Mind. (So I’m on record with this: I could’ve done without the elves & Toons, and I don’t think the review would have suffered without them. That said, such allusions make frequent appearances in Raymond’s imaginative & critical lexicon. His language & his ideas need them, even when his reviews do not. Anyone reading his work on this site already knows this.) Raymond proposed a challenge to Lucie’s methods, called for responsibility in directing or developing those methods. Keats wrote a letter in August of 1820 asking Shelley to consider the very same thing. Nothing post-post-whatever-the-fuck or polemical there.

Joan: Your review of Raymond’s review is a folly. It’s shamefully opportunistic & parasitic. You’ve called a duel & arrived with nothing more than a soggy chip on your shoulder. You’ve not posited anything intelligent or winning, and you’ve not argued convincingly—or at all, for that matter—for the way in which Raymond’s review failed to achieve its own objectives. It failed to meet your objectives, and you’ve manifestly failed to come clean about them. That makes you either a liar or a coward or both, as they frequently come as a pair. And as your objectives (now understood as obfuscations) were not solicited prior to the writing of the review, Raymond’s performance simply can not be evaluated based on your preferences or those weird little poking things you were doing, which you seem to think we’ll mistake for discernment and argument. You’ve misused the review site, further discredited your cause, and introduced an embarrassment into an otherwise respectful conversation with both Lucie’s work & Raymond’s review.

I can see you don’t want to make friends—I’m an introvert, so I understand & I don’t blame you — but at least make yourself worthy of your adversaries (and the passions alone will not qualify you). If nothing else, I think we owe that to this little effort we call poetry.

Susan Denning March 14, 2004 at 12:37 pm

I have read the book Trouble in Mind. I think to say someone is “abusing” their talent is a fairly harsh phrase. I also think it’s interesting that some of the letters to the editor are looking more closely at the review than they are at the book itself.

When I first read this book, I noticed: 1- several references to death, and 2- that the book is dedicated to a woman who died at the age of 39 (I later found out more about this woman, but more on that later).

Brock-Broido seems to travel back and forth between language that is ethereal and elevated–perhaps rarefied–and language that is more direct and plain. It strikes me as much more varied than many people who responded to the review and book seemed to think.

She often travels back and forth with language in the space of one poem. In “Boy at the Border of His Own Allegory” she writes: “A boy phones…/To tell me he has a shotgun/Muzzle to the inside/Of his Romance-speaking/Mouth.” The clarity of the image of the shotgun, contrasted with the “Romance-speaking Mouth”, illustrates a tension that is present throughout the book. This movement between levels of diction and presentation perhaps points to the poet’s attempts to find a way to use language to present the experience of being alive in the most complete, accurate, or satisfying way. Once I recognized this dance, I decided that the reviewer I had read online had either taken a rather cursory look at this book, or wasn’t as impressed as I was with this tension.

In Section three, this tension seems to become more urgent. Unlike the first two sections, that began more quietly, this section begins with “Self Portrait with Her Hair on Fire”. Hair can only be on fire for so long; how can a poem capture that moment? Although it is perhaps metaphorical hair that is on fire, it sets the tone for poems that begin to seem more obsessive; in part because they deal with ideas introduced in earlier sections, and in part because the poems themselves allow themselves more directness. In “Brochure on Eden” – which brings to mind the earlier “Some Details of Hell” – the poem begins, “I want to call things as they are” and then states a few stanzas later, in emphatic italics, “Things as they really are.” This section ends with “Fragment on Dissembling”, where the speaker directs a reader to “leave nothing still unsaid.” The fact that this is stated in a poem called “Fragment” seems to point again to the problem of language finding its right form.

What does it mean to be at the border of your own allegory? If an allegory is a story we tell ourselves to illustrate symbolically a deeper truth about life, then in “Girl at the Border”, Brock-Broido seems to be trying to figure out what some of the symbols in these stories mean; she writes “the night-/Engraving churchbells toll and in this/Constant cold I do not know/If tolling signifies/A death or marrying”. It ends with an image of the horse from “Beauty and the Beast”; but not just a generic “Beauty and the Beast”, but specifically Cocteau’s. This poem is followed by “Of the Finished World”, and coming as it does in this next to last section of the book, it seems to be leading towards, if not resolution, some sort of arrival.

The final section of the book opens with the poem, “Portrait of Lucy with Fine Nile Jar.” Lucy is the first name of the woman who the book is dedicated to, and the poem addresses her, “Around this death there was a final Nile jar/ of halo-light, where I am/ Thinking of you now”. The jar in this poem brings to mind the jar mentioned in Wallace Steven’s poem “Anecdote of the Jar.”, which is a poem about perception and how it’s represented. This echoing of Stevens seems particularly apparent since the author mentions in the notes that several of the poems’ titles come from titles of poems in Steven’s notebooks that he ended up never writing.

This section also contains “Self-Portrait with Her Hair Cut Off”, a response and amplification of the earlier “Self-Portrait with Her Hair on Fire”. And it ends with “Self-Deliverance by Lion”, which supplies the most important concrete information perhaps in the whole book, which is “she was found face-up on a cold March morning by the most menial and tender of the keepers.” Is this an obscure statement? After reading this poem, I decided that this might be the manner of death for the person the book is dedicated to; at the very least I think it is a metaphorical description of that person’s death. And I believe it is quite telling that Brock-Broido waits until the very end of the book to speak so directly about how the person died–even if it’s not the literal way the person died. It’s almost like the variations of still life and self-portraits and pamphlets have been looking through a kaleidoscope at the moment of this woman’s death. If this poem had come at the beginning, the poet would have been directing the reader very clearly towards her meaning and intention; by leaving it until the end, she allows the reader to take the journey herself.

I realize some of the conclusions I drew from this book are arguable. However, I believe I spent a lot more time with this book than the person who reviewed it online with Constant Critic. I think someone who’s reviewing a book for a site that gets so many readers should take a little more care.

After I wrote this, I looked up the name “Lucy Grealy” on the internet, and discovered that she was a poet who died at the age of 39 and was in fact killed by a lion. Even more importantly – in light of this book–she suffered from Ewing’s sarcoma of the jaw and was disfigured for much of her life. There was also some mystery surrounding her death. I also learned that her memoir, “Autobiography of a Face” dealt with how beauty is perceived by the world and how that relates to happiness. I think, in light of all this, that the tension I noticed between elevated language and plain language, and Brock-Broido’s struggle in the book with how reality is represented, can perhaps be seen as some sort of commentary on how Grealy’s appearance was dealt with by the world, and what beauty means.

And finally, I read a quote from an interview with Grealy that seems to point to many of the same concerns that Brock-Broido brings up in her book. This is quoted in the essay on Grealy’s death, “On Endings’ by her friend Ken Foster at the Land Grant College review (http://www.land-grantcollegereview.com):

“I was really interested in the ways that songs ended,” Lucy said. “Whether they just simply stopped or whether they tried to sum things up, whether they faded out in the middle of a line. You know, what they defined as a conclusion. Whether it was a conclusion like,

Jonathan Mayhew March 31, 2004 at 10:46 am

Does anyone edit these reviews? The prose here is hopelessly convoluted, the argument confused and disorganized. The descriptions of the poetry make it sound quite wonderful at times, yet the reviewer’s conclusions are mostly negative. I have no reason to defend or attack the poet here; I just want a coherent argument. “maintain against”? What does that mean?

Catherine Daly April 26, 2004 at 1:02 pm

I had a miserable $10 / hr job as a grocery store mystery shopper here in LA. Saw Carol Muske-Dukes (another review called Trouble In Mind the reverse of A Sparrow) and Lucie Brock-Broido in the grocery store a few days ago. There’s the quotidian for you. And an escape from it—I think they were buying wine, at the Larchmont high-end grocery store—

Of course, Brock-Broido was in town for the LA Times Festival of Books — the poetry tent there is always such an oddity since the LA Times being close to USC, and USC having the Anneberg school, the LA Times (and its festival) it always dominated by the networked-with-USC crowd, while the festival actually takes place on the UCLA campus.

Ray McDaniel May 10, 2004 at 2:36 am

One of the great things about our “letters to the editor” feature is that it provides the reviewers with feedback that encourages us to re-visit our conclusions; the letters also give the readers of the site the benefit of alternative takes on works we’ve reviewed. So I’d like to thank everyone who’s written to the site at all, and especially those of you who’ve written about Lucie Brock-Broido’s Trouble in Mind. I want to respond to some of the comments made in these letters, fragments of which I’ve excerpted below.

Jonathan Mayhew writes, “The prose here is hopelessly convoluted, the argument confused and disorganized. The descriptions of the poetry make it sound quite wonderful at times, yet the reviewer’s conclusions are mostly negative. I have no reason to defend or attack the poet here; I just want a coherent argument.”

Mr. Mayhew, I may have taken too much license in allowing myself to appreciate much of Brock-Broido’s writing while finding Trouble in Mind an overall disappointment. It’s unclear to me whether this strikes you as inconsistent and therefore objectionable, or if you cannot find your way through my hopelessly convoluted prose. Maybe both. If it’s the former, I don’t see how conflicting impressions indicate a confused argument. Trouble in Mind is a complex book to which I have a complex response; if that complexity isn’t a problem per se, then my prose must be the culprit. Unfortunately, I have no example of my hopelessly convoluted prose other than your question, “maintain against”? What does that mean?” My answer: it means to remain or stay in the face of an erosive force. For instance, the cliff maintains against the action of the sea.

In any case, thanks for the report — I don’t intend to confuse. For those of you curious about Mr. Mayhew’s own prose, visit his blog at http://jonathanmayhew.blogspot.com/, where he offers consistently smart and interesting commentary on poetry and much else.

Susan Denning’s letter begins by noting that she’s read Trouble in Mind; she then writes that “to say someone is “abusing” their talent is a fairly harsh phrase.” So do I, Ms. Denning, which may explain why I never accused Ms. Brock-Broido or anyone else of such a thing.

Ms. Denning writes further: “Brock-Broido seems to travel back and forth between language that is ethereal and elevated – perhaps rarefied – and language that is more direct and plain. It strikes me as much more varied than many people who responded to the review and book seemed to think.

She often travels back and forth with language in the space of one poem. In “Boy at the Border of His Own Allegory” she writes: “A boy phones…/To tell me he has a shotgun/Muzzle to the inside/Of his Romance-speaking/Mouth.” The clarity of the image of the shotgun, contrasted with the “Romance-speaking Mouth” illustrates a tension that is present throughout the book. This movement between levels of diction and presentation perhaps points to the poet’s attempts to find a way to use language to present the experience of being alive in the most complete, accurate or satisfying way.”

Good point, Ms. Denning, and good example. I should have made clearer the poet’s efforts to strike this balance within certain poems, rather than citing at full length those poems I found successfully balanced and setting them against examples I found less balanced.

Ms. Denning again: “Once I recognized this dance, I decided that the reviewer I had read online had either taken a rather cursory look at this book, or wasn’t as impressed as I was with this tension.”

That would be Option B, though it wasn’t that I wasn’t impressed with the tension so much as I felt the poet managed this tension less well than she could have.

Ms. Denning concludes her thoughtful and interesting reading of Trouble in Mind with the following: “I realize some of the conclusions I drew from this book are arguable. However, I believe I spent a lot more time with this book than the person who reviewed it online with Constant Critic.”

All conclusions are arguable, ma’am; am I to deduce from your reading of the book that you spent less time on it than a reader who might argue with your conclusions? That’s to claim that one specific reading establishes “ownership” on the basis of time spent on the task of reading, but the only evidence you cite to document your care and attention are your conclusions themselves, which even you admit are arguable. That we disagree proves nothing about our respective quality of “care”, though I certainly welcome the care you afforded the book, as well as your investigation of the late Lucy Grealy’s life and writing.

Although not cited by web address, you should visit Susan Denning’s magazine

Caffeine Destiny at http://www.caffeinedestiny.com/

Joan Houlihan, with whom we’re all familiar, takes me to task for the following:

“The abuse of one’s talent: To whatever degree such a thing is possible, we judge the act harshly, ” by claiming that “This puzzling, statement implies that Lucie Brock-Broido has abused her talent. But what does that mean? This, along with other of the reviewer’s innuendoes, is not only never explained or defended, it’s not even really stated. This sentence seems to say only that it may be possible to abuse one’s talent–and it may not. If it is possible, then “we judge the act harshly” (however such an act is defined–it is never defined here).”

Actually, Ms. Houlihan, the statement doesn’t imply that the poet has abused her talent. The statement leads directly to the claim that talents can lead their owners down dangerous paths, that talent used to achieve the poetic good can, if not carefully monitored and carefully applied, lead just as readily to folly.

Ms. Houlihan continues for a pace with some comments the logic of which I cannot track, but does respond to my sentence “…to clarify my mightily mixed feelings about Lucie Brock-Broido’s Trouble in Mind, which poses a number of problems, for all that it poses them prettily” with the following request: “please clarify mightily mixed feelings before setting pen to paper.”

I find this request baffling. Is not the function of the essay to demonstrate the act of clarification through reading, to make visible the essayist’s struggle with mixed feelings? What else is there? Should a reviewer banish all nuance and texture from the reading, and provide a simple thumb’s up or down? I have been operating under the assumption that a reader might want to know what the reviewer thinks as well as how and why. If you believe that the reviewer should offer less than this, should offer only judgment and no insight into process, then we inhabit mutually incompatible worlds of reading and writing. But for those of you who would enjoy more of Ms. Houlihan’s world, please look her up at http://www.webdelsol.com/LITARTS/Boston_Comment/

Jo Sarzotti’s excellent letter identifies me as taking “the posture of a disappointed fan of Brock-Broido’s who regrets that the new work lacks the density of Master Letters and that its language is “undirected.”” She proceeds to “suggest that McDaniel may himself be resisting something else in the new poems, which is a closer-to-the-bone revelation of the speaker’s feelings.”

Hm. There’s something to that, Ms. Sarzotti — in my subsequent readings of Trouble in Mind, I’ve kept your suggestion in mind, and I think I do associate the elevation of the language complicates my apprehension of the poet’s emotional register. Good point; I should have detected and addressed that response in the review. I’m still unconvinced of the positive relationship between this emotion and the structural soundness of the collection entire, but I appreciate your giving me a new way to consider the question.

And while I love the prose of Mr. Jeffr—Julli—