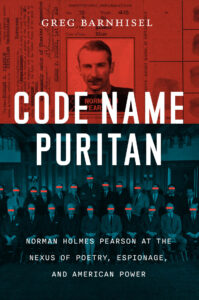

Devin King Reviews Greg Barnhisel's Code Name Puritan

What we’ve got here is a biography of Norman Holmes Pearson, famous in my circles for being H.D.’s executor. He wrote the foreword to Hermetic Definitions. But my wife, usually smiling politely about whatever poesy-academy book I’m reading, shows interest in the book due to its subtitle: Norman Holmes Pearson at the Nexus of Poetry, Espionage, and American Power. When I tell my buddy, the political poet, about the book, he goes, Well of course all post-war American art was funded by the CIA. And when he says this, he raises his eyebrows to suggest Men in Black.

An author, a press, needs to sell books. And, let’s be clear, Pearson was mostly a Yale professor. Is anyone but me gallant enough to read 330 pages detailing the life of a professor who, as it is mentioned over and over in Code Name Puritan, didn’t publish one book of criticism? So, inquiring minds: are there Tinker Tailor mix-ups amidst modernist lesbian and bisexual poetry salons in war-torn Europe?

Hard No: “For all the satisfaction running American counterespionage provided, Norm often regretted that he could not be in the field.” The reader enters a trance-state during pages detailing the bureaucratic functions of X-2, the department of OSS which Pearson oversaw during World War II. Folks describe Pearson as “the most important American counter-intelligence officer in Europe,” but, by important, they mean, a guy who was really good with notecards. Seriously!

Central to Pearson’s philosophy of counter-intelligence was not just gathering information but organizing it so it could be of use…he preached the gospel of notecards…(By the end of the war, Pearson’s team had catalogued information from eighty thousand documents and ten thousand cables onto a catalog of over four hundred thousand individual cards.)

So well-known were Pearson’s notecards, an employee composed a “ditty” inspired by Pearson, set to the turn of “I’ll be Seeing You”: “I’ll be carding you, in all those old familiar places.” I don’t mean to underestimate Pearson’s importance, but even David Simon would have a hard time dramatizing how Pearson’s “years [as a graduate student] learning how to ingratiate himself with authority figures and manipulate institutions made him a formidable bureaucratic combatant.” Pearson oversaw without seeing. The end of the war brings soft pleasures to Pearson and the reader: “As the war in Europe drew to an end, Pearson, who had long itched to see some sort of action…parachuted into Copenhagen to help extract X-2 double agents.” Back in the States, he enjoyed telling folks this was “the only time he ever drank himself literally under the table.”

Like any good thriller writer, Greg Barnhisel uses the spy stuff as a red herring. The book is more fairly defined by its storytelling around two things: 1) the foundation of American Studies departments in higher learning, most specifically at Yale, where Pearson studied and taught for most of his life, but as far afield as Japan and Australia and 2) how American Modernism—as represented by Pound, H.D., Carlos Williams, Moore, etc.—became, essentially, the post-war global signifier for Modernism within the academy. This was in no small part due to Pearson’s archival work at Yale’s Beinecke Library as well as his globe-trotting grandstanding as a soft-U.S.-government representative masquerading as a well-meaning academic.

Barnhisel has prepared. His first book, James Laughlin, New Directions, and the Remaking of Ezra Pound does what it says on the cover: Laughlin, as publisher for New Directions, used the then nascent paperback to overhaul Pound’s career while establishing New Directions as one, if not the, major-label American publishing house for global modernism. More recently, Cold War Modernists: Art, Literature, and American Cultural Diplomacy, tells the story my friend, the political poet, told with his eyebrows: how a bunch of bureaucrats used American culture to push priorities during the Cold War. These topics, these histories need to be written about; I wish Barnhisel was writing New Yorker articles rather than books. Trapped by his subject matter between the academy and popular history, Barnhisel has exciting twenty-page narratives that are rounded up by a factor of four with exacting archival scholarship. The stories he’s reporting couldn’t be told without digging into, and showing, the dry personal and government memos that resulted in you and me even gaining access to H.D.’s later work, but the research is not as exciting as the stories, and most of the stories could be told in a paragraph.

For instance: Barnhisel quietly tells the story of Pearson’s relationship to the Bryher Foundation—the foundation by which Bryher, H.D.’s long-term partner, funded writers, no questions asked. That is the story, but in the book it takes 2 and a half pages to tell. This elides—through a litany of the rare manuscripts that Bryher bought for Pearson personally, as well as for the Yale Library—into the nugget that Pearson and Bryher were happiest traveling together to all sorts of far-flung places, Greenland and the deep woods of Manitoba the most striking. Again, this is exciting, interesting stuff! But if the next wave of poesy-academic books about modernism is tasked with historicizing, rather than theorizing, methods of storytelling need to be rethought. Barnhisel has begun to do this. He structures the first half of the book as “first this, then that” biography, but when Pearson gets tenure and the story becomes habitual rather than processional, Barnhisel switches to chapters written around topics: American Studies, Poets and Networks of Poets, H.D. and Bryher, etc. It almost works, except it doesn’t: Pearson simply doesn’t have an interesting enough life outside of the folks he knew, and the things he did for those folks—like his work as a spy—were mostly bureaucratic.

Devin King is the author, most recently, of Gathering (Kenning Editions). He lives in Berkeley, CA where he has just finished editing the letters between Ronald Johnson and Jonathan Williams.