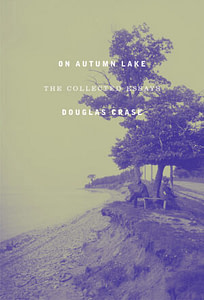

Devin King Reviews Douglas Crase's On Autumn Lake: The Collected Essays

“It was convenient for John Ashbery,” begins the first and titular essay of Douglas Crase’s On Autumn Lake: The Collected Essays, “and dumb luck for me, that I was living in Rochester and could pick him up at the airport whenever he arrived from New York to visit his mother.” And away Crase goes, eight zippy pages on the education Ashbery gave him while they took drives upstate. Two stories stand out: 1) Ashbery responds to Crase quoting Charles Olson’s “The Kingfishers” with “I always thought he had a tin ear!” and 2) Ashbery and his mother pass an asylum for the mentally ill with patients outside exercising and his mother says, “Isn’t that sad? I suppose you’ll go home and write a poem about it.” Even famous poets have mothers.

Then, just as you’re getting over the Ashbery gossip come two quick essays on James Schuyler. How does the first of these essays begin? “Because my name appears in his poem ‘Dining Out with Doug and Frank,’ I should probably disclose that James Schuyler was a friend of mine…” The New York School gave Crase a network of influence. But Crase’s essays and his poetry—recently reprinted in a collected, also by Nightboat—show him wrestling with that influence, and how to square it with his other love—19th century Americana. “One afternoon we were all discussing favorite poets,” Crase writes in one of the essays on Schuyler, whom he refers to as “the Day”:

…the favorite I offered was Whitman. Somebody laughed, and in a tone sophisticated people once used to indicate there was something embarrassing about Whitman said, “Oh, you probably like ‘Scented Herbage of My Breast.’” I went hot with shame, and knew I had to find a way out, when the Day spoke from the side of the room. “I think that is a beautiful poem,” said James Schuyler. It was thrilling to observe how the tables could be turned, and whatever new shame I felt at my near treason was transmuted instantly into emulation of this man whose honesty had saved me from betraying myself and my heritage for the sake of feeling momentarily snobbish and correct.

None of the essays Crase includes are snobbish, but they are sometimes correct. Their rhetoric is tuned to downplay the possibility of the embarrassment of the above afternoon, so everything has the tone of an erudite piece of PR that keeps repeating its safely wrought bullet points. Crase includes thirty-two essays arranged in five sections—most, not all, are about the New York School or Emerson. One low-key theme of the book is whether it is possible for Crase to truly explain his love of Emerson and Whitman to a bunch of New York hipsters.

Crase, who has received both a Guggenheim and a MacArthur, in addition to having his first book of poems, The Revisionist (1981), nominated for a National Books Critic Circle Award and a National Book Award speaks from and to the insiders of the New York literary scene. For those of us reading from outside, Crase worrying about taking Emerson seriously can feel a bit mawkish, especially when one of the essays is his Introduction to the Library of America’s two-volume edition of Emerson. I get it, you can’t always pick your mentors, you can’t always pick your surroundings, and you can’t always pick what attracts your soul. One day you’re applying yourself to Olson and learning his coarse sincerity borrowed heavily from the Transcendentalists; the next, you’re watching Ashbery flip through postcards in an upstate antique shop and accepting his gifts of Queneau and O’Hara.

The best of the essays are about Schuyler, and one suspects Crase knows this (they’re all at the front of the collection). Crase simply analyzes the relationship between Schuyler’s sincerity and his spare use of analogy:

We come to distinguish the coffee pot because it does not work, the dog because it howls, and the season of the year because it isn’t Girl Scout cookie time. The impression is of things left tactfully alone, to stand forth naturally, and there could hardly be a more loving technique. In the long run, maybe it’s true you can’t make poetry without annihilating the boundaries between the loved thing and your green thought of it. But a poetry that emphasizes distinctions, rather than analogies, is one way a poet may at least try to postpone the consumption in words of the very thing whose distinctive loveliness is what moved him to praise it in the first place.

Schuyler’s mastery of what Crase calls the “transitional meantime” becomes apparent in Crase’s precise discovery and exposition of Schuyler’s refusal of the simile. Less useful, to this reader at least, are the pages on Ashbery. It’s unclear whether this is because Crase plays defense for his old master from all the usual criticisms of obliqueness, or because Crase gets overexcited by exegesis meant to be private. Compare the clarity of the above on Schuyler with this:

Having seen what paranomasia can accomplish one will be ready to keep an eye on the other stylish figures we meet in Ashbery as well. For it turns out they can all be pressed into service to the same end, seducing the American self from its dual burden of infinitude and unique integrity. We have seen how apophasis can reduce that burden with a single coy negative: the soul is not a soul. We may not have noticed, however, that polyptoton was up to the same result, blurring persons in a way to suggest that identity, far from being unique, is likewise blurred.

It’s unfair for me to quote out-of-context something this technical, but Ashbery’s difficulty (misperceived or no) is precisely the moment when one expects the public-facing rhetoric of the other essays in the collection. Thinking about Ashbery has clearly been one of the great missions of Crase’s life, and if we have passages like this to thank for Crase’s own poetry, all the better. But I wonder if it might have been left in the daybook.

When the essays aren’t about the New York School and Emerson—there is a masterful, almost thirty-page essay on Lorine Neidecker reprinted from Wave Books’ beautiful edition of Neidecker’s Lake Superior—the New York School and Emerson aren’t far behind. In an essay on Michelle Jaffé’s sound installation Wappen Field, there’s a quick aside “toward a description of the sublime.”

In the nineteenth century, if you wanted to confront the sublime you stood on the pinnacle of the world and looked into the abyss of geological evolution. Time flowed boundlessly to your transparent eyeball. You were “glad to the brink of fear,” as Emerson said. People once got this thrill in the Catskills. The fortunate, who can afford the price of admission and travel, may get it still at Marfa, The Lightning Field, or Spiral Jetty—although these are increasingly destinations of privilege.

Another essay seems to be about Marjorie Welish and John Koethe, but Crase wants to write about Ashbery, Whitman, Emerson, and then, Jonathan Edwards. I’m not complaining. More American poets should ask what being an American poet means, even if it means having stranger (or even just less white and male) forerunners. The individual essays on Emerson are good enough that one wishes for an entire monograph on the great thinker, with Crase freed from his embarrassment and allowed to make an extended argument instead of a defense. But, then, I don’t know how much more Crase wants to say. One of the privileged destinations of his career is how little he’s actually had to publish to reach his highs: 120 pages of poetry, 400 pages of essays, a gossipy biography of a friend and his lover (Both: A Portrait in Two Parts, 2004), and an experimental book of criticism made up of quotes (AMERIFIL.TXT: A Commonplace Book, 1996). Instead of writing more, Crase’s essays show us how much he listened, first to Ashbery and Schuyler, and how much he read—primarily Emerson. “I suppose reality is always intransigent, especially when you try to build it from compounds as intractable as nature and democracy,” Crase writes in an essay on landscape painting. “Emerson must have had this in mind,” he continues, “when he spoke of the ‘odd jealousy’ of the poet who cannot get near enough the object.” Crase has spent his life circling his objects, never jealous, always open.

Devin King’s third book of poetry, Gathering, is out soon from Kenning Editions. He lives in Oxford, UK where he is working on a biography of Ronald Johnson.