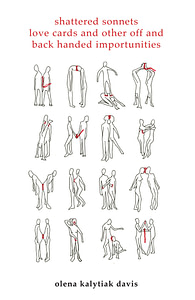

Ray McDaniel Reviews Olena Kalytiak Davis's shattered sonnets love cards and other off and back handed importunities

Olena Kalytiak Davis

Bloomsbury/Tin House, 2003

Reviewed by: Ray McDaniel

September 11, 2003

// The Constant Critic Archive //

Of the many and well-documented merits of recreational drug-use, the release of inhibition is both overvalued and under-appreciated. We are familiar—numbingly so—with friends and colleagues and other self-expressive sorts too drunk to stand or speak; no one who isn’t currently inhabiting this state would think to praise it. But the stereotype adjacent to this is that the release of inhibition is equivalent to incoherence, and as often as that may be true in practice, there is no theoretical reason to believe that the unbinding of restraint must result in droolery as opposed to drollery.

Meanwhile, way up in geosynchronous orbit over Anchorage, Alaska, Olena Davis is drunk on something: as the kids in Up With People used to say, she’s high on life! And as those intimate with the vertiginous know, such trips are equal parts euphoria, terror, and ass-out confusion—

So far, have managed, Not

Much. So far, a few fractures, a few factions, a Few

Friends. So far, a husband, a husbandry, Nothing

Too complex, so far, followed the Simple

Instructions. Read them twice. So far, memorized three

Moments…(from “a small number”)

The gods to whom Davis pays allegiance (for this is a kind of festival) are Spring and Love, and if that makes you shudder with the same spasm of sentimental menace that accompanies wedding toasts and creative writing classes, don’t worry. The poet has brought science fiction to pastoralism, made Marvell marvelous by a powerfully sustained act of distortion. Reading shattered sonnets et al is like reading an anthology of love poems condensed, crushed, laced with a mild hallucinogen, and distilled—via loop and tube and silly straw—into a mead and rainwater cocktail. (Here, have another.) The poems wobble, but in the main they do not fall down, and in a book nakedly devoted to the poet’s feelings, that wobble, the wobble on which the language smashes and slides, is of greater and more necessary interest than the stability always at risk. Sounds excessive, but you have no idea:

o liz

twixt impunity and impurity

lie i

and lies my artso, i will do as i am told:

love your neighbor as yourself

and put your cup up on your shelfask the kindly sexton for some kinky sex

on the slide and on the sly on the fence

(if you’re brave enough to try)FOR (listen up!) no concrete test of what is really true has ever been

agreed upon.(from “letter home”)

The poet: close enough to the sleep of reason to have her social editor lapse while the Cat in the Hat seizes control of the house, her words, her very capacity for rhyme. Rhyme, both literal and as signature concept, takes it on the chin here: shattered sonnets stutters with rhyme of sound and historical sense, as Davis continually discovers that there is no sentiment for which she does not have a prior poetic partner: Berrigan, Plath, Hopkins, Sexton. These aren’t name-droppings; these partners are swung into the revelry and spat out just as quickly. The charm of this rests in Davis’ refusal to sacralize her agents, be they inspiring angel or mere device. Girlfriend is after LOVE and SPRING and SOUL, and nothing, certainly not propriety of any stripe, is going to get in her way:

hey, you, lover of truth, you don’t

look so good.ringstraked

and freaked, yrslove…derailed and defunctive… and yrs and yrs and yrs…

I listened to everything everybody says.

(said, yeah yeah yeah, we heard…)never got ahead.

never lost my head. I was losing my mind but not losing my

head.it tingles and it pricks, like nettles, like devil’s club, like nasty

little

thoughts and rills.scortatory, addicted

to borage and hellebore, yrs, love, O, look,

a small sorrowsown in with the sparrow grass!husbandman and Wife.

lordandlover and other.

it didn’t matter the end would be the same.

the lovage and the borage. the barrage.turns out, I am the cock of the rock. gallinaceous and pug-

nacious and (pang): I guess,

a little disappointed.like beckett in spring. ping.

like beckett in spring.(from “this is the kind of poem i’m done writing, or,

a small pang in spring”)

This is something between reckless and fearless, and while I cannot decide to which end the poetry tilts, I’m not sure it much matters. Like the previously-considered Timothy Donnelly, Davis isn’t concerned with excess as an idea so much as a practice, a commitment via which the fray and play of language froths over into a kind of mimesis that is reproductive rather than reflective. And this forces us to reconsider what we usually meant by risk-taking, which begs indulgence of one kind of restraint (“Dare I speak?”) against another (“If I do speak, I must say only what I must and no more”) to create the standard tensions of poetic excess. Most poems implicitly question how far is too far to go, and derive energy from the alleged validity of that tension. Davis, of course, could not care less; indeed, for all their formal play (a master’s play, too), her sonnets owe nothing to the standard of the ur-sonnet and everything to the poet’s hellacious abandon. There’s no fear here, but that isn’t to say that we read confidence in its place. The action of Davis’ language is so apparently enslaved to its necessary compulsions that questions of posture and attitude diminish, iris, and finally collapse into their own self-importance. Pick up any book at random after an evening with Davis and the words therein will strike you not only as prim, as controlled, but frankly donnish, marmish and as bitter as over-strained tea.

In this sense of excess, of production and re-production, Davis circumvents poetic construction as mechanical and pushes hard for something better lent to organic metaphor. shattered sonnets is indeed like the poet’s obsessive and possessive Spring (“O, to see you again. Covered in spring.”): it’s glorious, and it’s also a mess, and the messiness both defines and detracts from the glory. Much poetry may well be over-gardened, sculpted into topiary approximations of what language might offer to life, and Davis writes well about the consequence of this in her dedication, ‘sweet reader flanneled and tulled’:

Reader, toward you, loud as a cloud and deaf, Reader, deaf

as a leaf. Reader: Why don’t you turn

pale? and, Why don’t you tremble? Jaded, staid

Reader, You—who can read this and not evenflinch.

Well, the Davis cure for this as extreme as you might expect. Her poems seek to both analyze and occupy the intoxications of Spring, both as historical lyric force and febrile imagination, mulch and shoot. What you see here is thus a combination of Spring’s drunken relief, life uncontrolled and untrammeled; you also get to see the spasticity of new life, its hunger, desperation and ruin. But remember: you are drunk, and the toxin is as sweet to you as is the wine.

I cannot guess how this book will read ten years from now, if it will have the progressive taint of a story over-told or if it will wallop and refresh anew, whether it will partake more of drunkenness (which embitters) or true Spring (which, goddamn, works every time) or achieve some as-yet imagined effect. For now, Davis seems to understand that the lust(s) she seems chained and sweet hell-driven to record require apologia: she asks of the Lord

Feed Me

Hope, Lord. Feed Me

Hope, Lord, Or Break My Teeth.

As if any god could survive such devotions.

COMMENTS:

Jorge Sanchez September 13, 2003 at 12:22 pm

I sit beneath the overcast skies

of the Middle Middle-West,

a full-size industrial table

saw wharring dowels into trim,

and the thirst slaking droplets

of Ray McDaniel’s quickened

critique gives me something

to go out and read, consume;

Mr. McDaniel:

Once again, I am made gleeful by your prose. Normally, I pleasure in the puckish joy of your regular dismantlings of career and canon (not that I am anything but a pacifist; not that I am anything but a smile-and-nodder). I am glad to see you’ve put down your caustic scythe (for now) and picked up the shiny sinews of the feast-ox, lighting the fat-girded femurs, making a torch of bones;

Hooray for the appearance of Ms. Davis’ second book.

-J

Heidi Peppermint November 13, 2003 at 8:55 pm

Hi. I really enjoyed your review and appreciate the distinction you make between excess as poetic practice and poetic idea.

Chrs, Heidi