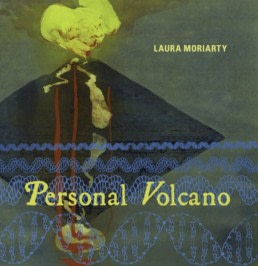

A Personal Volcano Cracks in the Holocene: A Disaster Series

Let it be said from the outset that no book review, no exegesis, no close reading will ever approach the utter richness and specificity of a work under consideration. In other words, no metatext can quite match the poetic world it attempts to reach. A book overruns its seams in a way that always disrupts and collapses the critic’s gloss and her net of explications. This could not be any truer of Laura Moriarty‘s newest collection, Personal Volcano, which is a hybrid text of overlapping registers and affects, volcanology, intimate history, ecopoetics, and social practice—spilling its timelines, queries and dreams inside out, emitted, analogic.

Is this a geological cataclysm

or one of spirit or body?

Although organized in twelve sections, the book bubbles up, erupts, straddles, and cracks the crust of our knowledge, releasing its violent analytic, eyes wide open on “this epoch or extinction or whatever this is.”

The last sentence of Nadja, André Breton’s 1928 surrealist novel, reads “Beauty will be CONVULSIVE or not at all.” Grounded in extensive research which takes the author from Mount Shasta in the Cascade Range in the Northern part of California to Western Iceland and Mount Pelée at the Northern end of Martinique, to name a few sites, Volcano teems with a lexicon whose scientific precision and sheer abundance produce inexplicable splendor. Lava, ash, and gases punctuate the various eruptions while calderas and fumaroles exert an eerie power of seduction. Scoriae, schist, and fire plumes rain down on earth, coruscating in a hot flash. When we stumble in section one, entitled Glass Action, on “nuées ardentes,” we seem to read a mute citation from Mallarmé, but quickly come to understand it as an incandescent cloud of ashes. If a volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary object, then Moriarty offers her lessons on “volcanic genesis” and its aftermath in a way that makes a leap between rupture and rapture. The ensuing explosions convulse world and word, sharing the same space.

Blood in our veins totally alive

inside our pink hearts (our skies)

Lately, the thrust of a number of postmodern texts is to fissure the old models of self-expression, giving rise to lyric productions that emphasize language’s dimension as a medium of consciousness, wherein the stream poet/world/word mobilizes social and political change. Whether it be the docupoetics of Mark Nowak, the investigations of Louisiana State penitentiary by the late C. D. Wright, Divya Victor’s critique of race and empire, or Tracy K. Smith’s erasure poems, poetry today tends to be a socially engaged practice whose horizon is less the unitary subject as paradigm for reality than a desire for collective transformation.

Taken in this perspective, Moriarty’s Volcano shares in these developments by radicalizing the medium of poetry as a construct for research, critique, and prophecy. Within these pages, the writer-volcanologist re-imagines the poetic act to highlight the intersections, not only between literary genres — travelogue, prose poem, dramatic monologue, investigative lyric, autobiography — but also between various discourses, voices, and rhetorical strategies. The upshot of such a heteroglossic, relational structure is that Volcano complicates each individual strand and doubles it with a persistent questioning of one’s own positionality:

But where are we in all this stone?

Such a dialogic approach opens up a space to juxtapose history and the present moment, popular culture and scientific research, avant art and “clues to the end of the world.” In other words, whether she ventriloquizes Isaac Newton or steps into the diegetic world of Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth, or else indexes capital’s ecological malfeasance, the speaker in these poems doesn’t so much link knowledge to action in a pointy, didactic way, but lets the various seams, channels, and bridges become a prism for a charged awareness of what the stakes are at this precise moment of the Anthropocene, or as one stanza has it: “what that means about how we are FUCKED.”

Keeping in mind Adorno’s famous assertion that to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric, one can argue that Moriarty implicitly reprises that problematic by pressing forth a similar thorny question: is it possible to speak of fracking, global warming, famine, extinction, and irreversibility in a lyric? Maurice Blanchot’s The Writing of the Disaster, which, in a fragmented and aphoristic vein, evokes the major agonies of the 20th Century—Hiroshima, the Holocaust, war—is here a paradigm to echo. With Personal Volcano, Moriarty reaffirms the poet’s task to level her eyes, “strangely sharper” on “estrangement, catastrophe,” calamity: the disaster series of our times.

each history different

longing the same

One of the most haunting and effective compositional strategies consists in imbricating the geological axis and the personal as if the breaking of the tectonic plates, the fiery explosions, and the hotspots were things of the heart. The book’s opening plays out the devastation on the modern couple with characteristic—if unsettling—candor:

MY VOLCANO

takes the form of a mountain or

GLASS ACTION in this case ephemeral as when passion’s

end is evident to both lover and other who, fucked from

the beginning, but more determined for the fact of the DISASTER

answers every day the question of who loses whom or what when LIFE is no longer

organized around LOVE leaving EARTH and VOLCANOES intact except in dreams which reprise

how it all lived and died in a landscape bereft of everything (one) not left alive

This extraordinary entrée en matière which delineates desire’s catastrophic rupture will from now on show all volcanic processes, whether real or imagined, prehistoric or mythic, crystallizing the double nature of this explosive matter.

The fifth section, “Invisible Sun,” unearths autobiographical threads of the author’s life with her husband, Jerry Estrin (who passed in 1993), which stand adjacent to the Minoan eruption of Thera, dated to the mid-second millennium BCE. On the “disaster table” of that inexpressible grief lies a photo: “Here he is pictured there among the other dead.” Seared into the text, the volcano is subject to its own fire, literal and figurative.

The authority of Volcano derives in great part from a capacious range of cultural references that assert their presence in recognizable signs embedded in the lines like crystals in a geode, translucent and sparkling. In this strategic focus on “rocks, humans, objects/waves, history” — what a spectacular raccourci — one hears less the music of ancient bards than that of history, science and art. From the mustard gas of the Great War to Superman in a “Jungle Devil” TV episode, from geologic periodization to Virgil, from Bob Dylan’s “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” to Meredith Monk’s Volcano Songs, from an art installation by Tom Joyce, a blacksmith, to Frederick Spencer Oliver, author of A Dweller on Two Planets, a novel about Atlantis, not to mention the profuse volcanic know-how of where and when, and the up-to-date map of profiteers that overlays the entire composition, Moriarty’s work displays its erudition with the insouciance of a postmodern practitioner, mixing high and low, blasting the borders as she goes. The radical gesture here is to release “subjugated knowledge” toward epistemic transformation: “charity, compassion, nonviolence.”

“No geology/ but in things” gestures at William Carlos Williams’s imagist mantra to keep the poem squarely on its referents in a direct and concrete way. This requires an attention to the tangible world around us, as well as to the materiality of the very language with which to convey said world. The import of such a guiding principle can be best gauged in the ninth section, titled “Analogic Geology,” where Moriarty makes legible late capital’s ecocide by naming the guilty parties and their irreversible impact on the global environment. Reminiscent of Kofi Natambu’s poem, “The Semiotics of Apartheid,” which calls out the U.S. companies that invested in South Africa—”Dow Chemical Sears Gulf & Western Standard Oil Texaco Exxon/ General Electric Mobil K-Mart McDonald’s/ take your pick”—this section delineates a toxics map, complete with names of plants, locations, and poisons.

Defined by greed, refineries and other industrial entities “run by Chevron, Phillips 66, SHELL/ Martinez, Tesoro, Valero, and four/ chemical plants operated by Shell, General Chemical, DOW, and Hasa Inc.,” discharge their carcinogenic compounds which build up in the human body and eventually end up as “SUPERFUND SITES,” so labeled by the EPA as lands contaminated by hazardous waste:

driving a few to the hospital

with nausea from a burning

smell coming from the WATER

by way of the refinery

or from TANKERS—extensions

as they are of the industry and

industrial CAPITAL

In Volcano, the performance of such ecopoetics doesn’t limit itself to the indictment of environmental crimes committed under our watch, but connects to a decolonial perspective that finds its meaning in acts of solidarity and disobedience by grassroots movements during the 2016 Dakota Access Pipeline protests:

STANDING ROCK SIOUX and many others in a convocation

of TRIBES larger than any since the nineteenth century

put themselves on the line as WATER PROTECTORS.

They pray and sing. Others donate and call.

Watch and pray. I guess this is PRAYER.

To think in decolonial terms also means acknowledging territorial theft: “as Hawaii or Yellowstone stolen places/as what place isn’t in some sense.”

Perhaps some readers who have followed Moriarty’s work since the early editions will miss her distinctive lyricism so perceptible in Rondeaux, Symmetry and many others. Undoubtedly, in Personal Volcano, logopoeia gets the lion’s share of this artistic production, while sight and sound drop back — ever so slightly— to let the magnitude of the message draw our attention, arrest us within this “molten scene.” However, it would be an error to think of this as a departure from lyric practice, as Moriarty expands her modalities and, in effect, rewrites the Poundian dance of the intellect towards new and radicalized intelligibility which makes its own specific sound, whether it be a racket or chant.

Having traipsed from Richmond, California to Reykjavík, Iceland, having traced the erupting “SULFUR DIOXIDE and other poisons,” having peered into the heart of the volcano and seen the “fiery crack in the world,” the poet emerges like a modern Cassandra, an eco-seer, “looking down the barrel of a gun,” to hurl her prophecy. Personal Volcano is a poetic event of the highest order and we need its counsel now.