The Mule Is Burning: Dwarf Fortress' Poetics of Endless Context

Joe Hall

Dwarf Fortress is an open-ended civilization simulator designed by Tarn and Zach Adams and in continuous development since 2002. “Civilization simulator” may bring to mind a God-like player whose commands move mountains. But Dwarf Fortress’ dwarves don’t love following orders; cause and effect are complex; outcomes are often systemic and betray intentions. Playing Dwarf Fortress is like an English professor operating a nuclear reactor. Its interface is a strange organ of levers, dials, and gauges. Toggling around may result in the flourishing of your dwarven home or may lead to a downward spiral in which all your citizens kill each other or die of sadness. Dwarf Fortress is impossible. Getting anything done is complicated. Also, the graphics suck, the interface is garbage, and there is no narrative.

Yet this impossible game has a cult following. It’s the only one I’ll watch someone play, partly because it’s so difficult, partly because the game inspires compelling exegesis. Why does it inspire compelling exegesis?

Description. Gorgeous, strange, grotesque, banal, and exhausting waves of textual description.

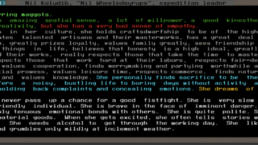

The graphics are crude (not retro) ASCII but you can stop the game at any point to access text describing the dwarves and the world around them. Where visual objects are empty balloons in most games, Dwarf Fortress’ Foucauldian eye vivisects simple surfaces into complex depths and translates this all into endless coils of text. For example, here’s the dwarf Nil Koludib:

The endless textual accounting gives Dwarf Fortress’ digital world a peculiar sort of materiality. What text is this sock made of? Who does it belong to? What is the status of Nil Koludib’s organs? What words has Zaneg Racklocks the Speechless Wrath engraved into a wall? “Engraved on the wall is a finely designed image of a mule. The mule is burning.” That mule was a mule someone saw, burning, and now it is in rock.

The game’s complicated (cluttered?) present is the product of a mind-boggling past. From its inception, the game has procedurally generated a world with things that relate, evolve, die, and reproduce. And it continues to try and account for vast arrays of things; everything has its own condition and history of relations. There is a geology of the world upon which the dwarfs perform their own stratigraphy, burrowing beneath layers of dirt, mineral, aquifers, and strange subterranean ecologies. There is the stratigraphy of a dwarf’s body: skin, organ, bone, thought. There is the stratigraphy of objects: maker, owner, condition, history. The game’s crude graphical display floats on an ocean of data. In this ocean of data, Dwarf Fortress proposes the intense relationality between people and things: everything carries its history and most events leave their mark. In generating and coordinating all this information, the game can still crash new CPUs. A player might ignore much of this history—but it’s there.

For this reason, Dwarf Fortress is unlike other games that procedurally generate worlds (No Man’s Sky, Minecraft). These games allow their players to enact Robinsonades, the fantasy of a single individual building a hermit civilization from scratch in an island of wilderness presented as a blank slate. Colonialism without context, the production of the desire for terra nullius. Though Dwarf Fortress is thick with context, it still rests on the dangerous colonial fantasy that there is an unpopulated slice of the world left to settle.

Dwarf Fortress’ capacious accounting of stuff (rendered fat, damp shoes, memories, mushrooms) also creates dramas between nature and culture. In Grundrisse, Marx posits a dialectical relationship between the conditions of production and the relations of production. Community is defined by its relations to the conditions of production. Production changes the conditions of production and, in turn, the relations of production. That is, making stuff transforms ecologies, transformed ecologies transform social structures. Abstraction! However, this is not the case when Dwarves deforest their immediate surroundings then have to travel dangerously far or deeper into the earth to meet their immediate needs. The danger this exposure creates may move a player to form a militia, a hard division of labor with large social consequences. Extraction spawns militarization.

Causality can flow the other way too: the accumulation of surplus attracts more settlers, a larger, wealthier fortress eventually attracts nobles. Nobles might demand the production of certain goods and require larger well-appointed living quarters. Production of these goods may require the dwarves to intensify the exploitation of their environment in search of novel raw materials. Case in point, nobles’ quarters are literally carved out of the earth. These concerns stage an intense dialectic between the conditions of production and the social relations of production as the shifts in social structures ravage surrounding ecologies.

This is to say, it wasn’t until playing (overwhelmed) Dwarf Fortress that I could follow certain Marxist threads more clearly. And there’s another essay here on how the game values reproductive, affective, cultural and waste labor by making it integral to the coherence of dwarven society. If all dwarves do is market production, they might start throwing tantrums or lay down in their workshops and die of despair. Or the colony may drown in rotting clutter. None of this drama is fun.

The more I peak inside of dwarven heads, the more I want to make their happiness their work. But this is also difficult. Some dwarves have material and emotional needs that can’t always be met. Every fortress is tied to the world, so every dwarf is subject to random events, even if it’s simply getting bad news from afar. Stasis isn’t possible. Yet sometimes the mutation of social relations and the built environment isn’t traumatic for everyone.

An organization of farmers petitions for a guild hall. If you build the hall, they begin to educate each other. The social relations of production change, become more horizontal. Temples, libraries, meeting halls. Dwarves desire each other. A robust municipal infrastructure makes that happen. I think of Giuseppe Zibordi’s socialist-municipalist politics, which “is about little struggles, humble battles that would make an outsider laugh.”[1]

And, you know, let me not overstate this: this isn’t a perfect game, or even close. It’s got problems in its assumptions. But I’m interested in the potentialities in what it accounts for and, accordingly, what it makes an object of potential concern for its players.

What does this have to do with in-game poetics? Lots. The game is sprawling, overlapping skeins of historical, personal, cultural, and ecological data. Endless context in dynamic relation. And I love poetic texts—and poetics— that cannot be fully disentangled from their place and time.

We now arrive at the fact that there are no poems in the game. Rather than poems, the game procedurally generates creative descriptions of poetic forms. Two examples: 1) “A ribald poetic form intended to make an apology concerning nature” (brief!); 2) “A solemn poetic form intended to express grief over mining, originating in The Splattered Confederations. The poem is a single octet. Use of internal rhyme, assonance, and vivid imagery is characteristic of the form. Each line has six feet with an accent pattern of unstressed-unstressed-stressed (qualitative anapestic hexameter). The ending of every line of the poem rhymes with every other. The fifth line of the octet contrasts the underlying meaning of the second line. The second line of the octet is required to maintain the phrasing of the first line. The eighth line of the octet uses the same placement of allusions as the first line.”

The variables of the game’s poetic forms are capacious: tone, subject, cultural origin, rhetorical situation, point of view, syntactical and grammatical patterns, meter, stanza and poem length, figurative language types, sound. Reading lists of forms the game has generated is like traversing Borges’ Librarian of Babel. To interact, one could search the endless arbitrary combinations for meaning, or search for a form that somehow fits their sense of the sublime. One could wonder what a linguistic system would look like that could produce “spondaic hexameter,” impossible in English.

Through their powerful synopsizing modes, other outcomes of Tarn’s poetic machine make me reconsider formal relationships to real world genres: “A dramatic poetic form intended to make an apology concerning war, originating in the Tan Empire.” This one is in “quantitative spondaic pentameter,” clanging and honking away. I think of a class I had taken on soldier poets, where we often considered these poems as anti-war. But the word “apology” rings like a bell, disaggregating that form. Much of it, most of it, was narcissistic “shoot-and-cry” lit, the killer revolving around the pain of their own guilt, carrying forward the erasure of their victim. “Apology for” seems rather more appropriate than “anti-.” As you continue to play, you begin to think past the space of play, about your own relation to lists, to their form and content, their cultural boundaries and determinates.

But this list of forms isn’t the game. This is what I love about it. Any one poetic performance is just a seed of data. For it to be meaningful, you have to investigate its place in the game’s vast honeycomb of context.

A dwarf reads a poem to two dwarves speaking to each other in the evening. One has recently, happily, given birth. One is upset at having to live in a crowded, bare room in dwarven city under siege (or perhaps its rioting cops?) that is having trouble providing for its citizens. This second dwarf can no longer go beyond the city gates to gather wood. Most of her friends are in another city. She hasn’t heard from them because of the siege. They turn to listen to ribald puns about shoe-making from a dwarf from a different city who became a poet after seven years as a butcher. This makes the second dwarf, the sad dwarf, happy for a moment. Yes, this.

Dwarf Fortress is full of these polysemous moments, of signals flaring, of requiring the player to translate those signals within the thick context through which they emerge.

[1] Giuseppe Zibordi, “Primavera di vita municipal,” Avanti, Sept. 8, 1910.

*

Joe Hall is a deprofessionalizing academic in Buffalo, NY and the author of four books of poetry, including Someone’s Utopia (2018). If you’re reading this, consider supporting the work of Black Love Resists in the Rust through a recurring donation.