A Practice of Immersion: Gloria Frym on Reading

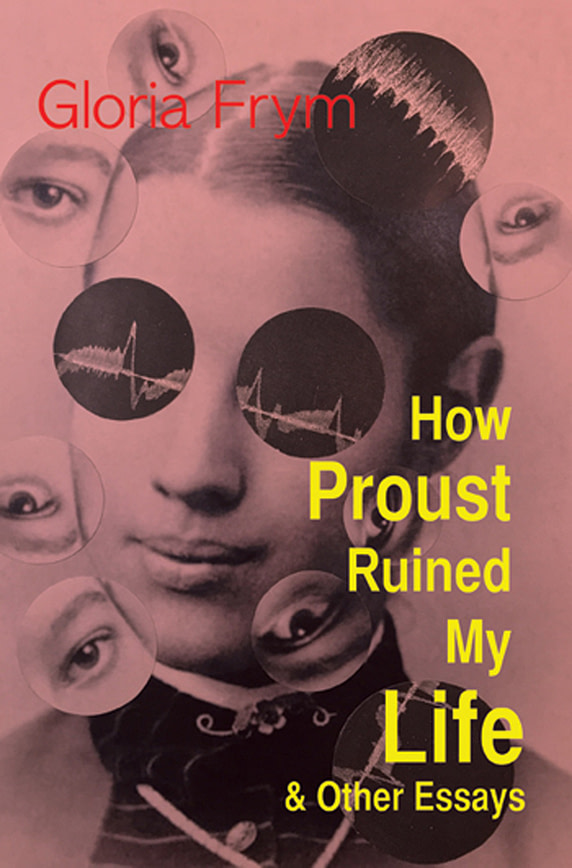

The writing gathered in Gloria Frym’s How Proust Ruined My Life and Other Essays is personable, generously gifted to readers. The essays do not promote a particular theoretical angle, nor do they seek to impose a dominating theme to determine how or what we might read. Instead, Frym explores her life as a reader and, incidentally, shows what it means to write in relation to a reading practice. The collection offers a range of topics, such as her experience teaching incarcerated men and women in Bay-Area prisons, readings of classic fiction, including Madame Bovary, Chekhov’s stories, and Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, along with encounters in American poetry through the works of Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, and Lorine Niedecker, among others. Frym writes also to commemorate the work of important friends, writers from whom she has learned to write herself, like Robert Creeley, David Meltzer, and Lucia Berlin. Reading and writing are acts of love, and the pathways of affection Frym enlivens helps readers reflect on their own affections for books. She especially directs attention to the ways form inhabits our thinking, and how the textures of our thought are coordinated through an ongoing practice of noticing how words orient attention to the present.

An essay early in the book reflects on reading habits. Consider “the practice of immersion” that reading becomes for those of us consumed by texts. “This habit of reading,” Frym observes, “is a form of protectionism, a kind of amulet to counter the assault that threatens to drown us in tidal waves of information, political corruption, multi-nationalism, corporatism, tribalism, and just plain human brutality.” The “habit” of reading “tries to corral the random and creates form for the mind,” Frym writes, tracing her understanding of form etymologically to a Latin sense of fictio—fiction—“‘to form,’ to give shape.” From a dynamic formation of the personal interior, reading is seen as “an act that orders the world” (42). As an act of order, or imagining, her excitement for reading is infectious. For instance, as I was reading, I would frequently stop to go hunt down an old book, or I’d Google translations of those I had yet to read. I recalled my own stymied progress through Proust’s opus as I considered Frym’s key essay on À la recherche du temps perdu. Her candor is lovely, for she discloses how she read Proust—all of Proust, along with accompanying biographies and critical studies—with others in a reading group, meeting frequently to discuss the author. “Proust, we discovered, is not a difficult writer,” she says. “The only thing he requires is patience and desire. Relatively intelligent persons who read regularly can easily enjoy him. He does not have to be academicized. But he does have to be loved” (51). The essay goes on to elucidate not Proust so much as a love of reading, and the loss that comes with the completion of a prolonged commitment to another fictio—the unfolding and infoldings of a body of feeling. Part of the experience of her reading of Proust is implicated by a love affair that comes to an end around this time. Frym’s candor of desire for physical love, and a love affair with words, imparts a material obsession to transcend the limitations of the self. At those limits where love’s boundaries are exposed at the physical edges of meaning, the reader-lover approaches an interior ruination. “After what became a protracted end [of the affair],” acknowledges Frym, “I picked up the first book of Recherche. I read two pages. I put the book down and wept. I was not ready to go backwards” (54).

In a 1997 talk delivered at Naropa University titled “Recombinatory Poetics: The Poem in Prose,” Frym examines the relationship of prose to verse, articulating “a counter-poetics that is strategic, not categorical” (89). She brings pressure to the notion that poetry only exists as broken-line verse, pointing out how the most appealing writers often resist easy genre identification. Melville, Rimbaud, Baudelaire, and Proust expand form beyond easy genre or marketing categories with novels that dissolve into performative poetics, or with poems that register modernity in prosaic structures, implicating the sentence, not the poetic line, as an organizing force in the distribution of poetic urgency and anti-lyric utterance. Frym reminds us that after extraordinary investigations in prose and verse early in the twentieth century by Gertrude Stein, Jean Toomer, and William Carlos Williams, the notion of the modernist prose poem became a standard means of inquiry for writers like Leslie Scalapino, Carla Harryman, and Renee Gladman. “The strategies of the poem in prose are elastic,” Frym argues, “because there is no emphasis on attention to regular meter or breath or sound patterns as there might be with broken-line poetry. The techniques of the poem in prose open up new possibilities for absorbing speech, text, philosophical exposition, even subjectivities now able to exert or disguise themselves into objectivities via sequencing” (93). In another essay on the “Poetics of Prose” Frym examines what she calls “the kind of prose fiction that, in the consumer culture of late and lamentable capitalism, often poses a ‘marketing’ problem” (116). Such writing “depends upon hybrid, plotless, and unclassifiable forms,” and often is wrongly associated with “poet’s prose, poet’s fiction” (117). Instead, Frym observes a shared sensibility among certain writers, rather than an informing style. She goes on to give examples of the kind of economy of writing she has in mind, one that prefers compression and directness of thought to more Baroque structures. “If I had a motto for the short story informed by a poetic sensibility,” she says, “it might be To the Quick. Or as Raymond Carver said, ‘Get in, get out. Don’t linger. Go on’” (118).

By inverting Pound’s dictum that states “[p]oetry ought to be at least as well written as prose,” Frym argues, “Prose ought to be at least as well-written as poetry” (121-122). She reminds us of a necessity of outlook toward life and language, toward form and its interior force on a reader’s appetite. For instance, Chekhov’s plotless stories inspire Frym’s affection for the pointless, for in those areas of concentration, where a dominant theme or concern of a character never materializes, the possibility of discovery exists in the attentive focus of the author to an exterior world. Such attention carefully acknowledges language’s presence in the making of that fictio Frym describes earlier. A balance of forces is presented to readers, where words disclose the possibilities that exist between author and text.

An essay toward the end of the collection written in memory of the short-story writer Lucia Berlin, who found posthumous literary acclaim with the 2015 publication of short stories titled A Manual for Cleaning Women, reflects on writing, success, and literary obscurity. Frym says, “If I say to others, to students, to write to find out, write what you can’t know otherwise, write into the unknown, forget the clichés of ‘finding your voice,’ and ‘write what you know,’ I should take my own advice here, trying to untangle my feelings” (177). Frym explores her feelings as she wonders at a division between the small press literary outsider and the sudden celebrity status of her late friend. The dissonance between the two Lucias of literary fame and obscurity drives Frym to consider what life means in relation to writing and to a readership. A key question throughout Frym’s work returns here with force: What is the contact point between life and written art? For someone like Lucia Berlin, the division was in a sense minimal, insofar as she lived alongside the creative forms she imagined. For friends like Frym, the sudden publicity of the previously unknown author disturbs a fragile sense of how the practice of writing both is a determination of form and order on the chaos of one’s life, but also can become a public item of consumption. The personal stakes of creative form that guided Lucia Berlin’s life finds in new packaging an afterlife determined by industry and market. “Am I any closer to naming the feeling I began to investigate,” Frym asks. “Doubtful, but it is the whole of her, the literary and personal being I cherished” (183).

Andrei Tarkovsky once said, “When I speak of poetry I am not thinking of it as a genre. Poetry is an awareness of the world, a particular way of relating to reality” (Sculpting in Time, 1986). Similarly, Frym’s essays draw attention to ways certain writers have strategically approached the diverse conditions presented to them, pushing into the fiction of form to better understand what it means to read and write from our varied stakes in time and place, with connection to those famous or not, to texts that are well known or little read. Her work is a reminder of the fragility of human needs and placements in relation to shifting social environments. How reading invigorates our lives matters. Frym’s essays teach us to listen and to understand the immersive present writing can help us comprehend.