Finding the wifthing in Pattie McCarthy's Found-Text Sonnets (& in Pregnancy)

Sarah Heady

June 25, 2021

Elecment Series #10

the text begins imperfectly with blank / spaces where her body betrays her / in a new way or an old way that’s / new to her

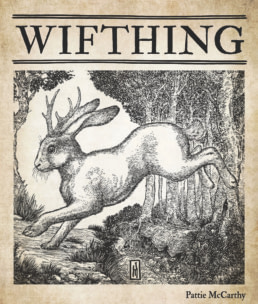

Pattie McCarthy’s newest book, wifthing (Apogee Press, 2021), extends the poet’s ongoing project of excavating traces of female, and often maternal, experience from the Western historical record. McCarthy’s seventh full-length collection and her sixth from Berkeley-based Apogee, wifthing continues her obsessions with the fertile female body, with childbirth and childrearing, and with women whose lives are preserved in—and extrapolated from—traces of found language that she enlivens by running them through a kind of poetic composting process.

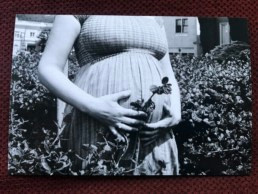

I’ve read McCarthy’s previous books over the past decade—years in which my attitude toward children and motherhood changed dramatically. In earlier versions of myself, starting with the shortly-post-college me living in Philadelphia (where McCarthy loomed large on the scene), I probably registered her visceral and intimate explorations of fertility and motherhood with fear, apprehension, distance; later, with curiosity, fascination, perhaps longing. But wifthing is the first time I have experienced McCarthy while in an embodied state of maternity myself: I read the book, and wrote this review, over several weeks in the winter of the worst year—the span of weeks, as it turns out, that composed the first trimester of my first pregnancy.

*

The tone of this first trimester seemed to me perhaps a preview of the “lying-in” period that (fingers crossed) awaited me: the time following childbirth in which exhaustion reigns, time blurs, and the needs of the body dictate all else. Luckily averting the nausea that haunts early pregnancy for some, I was nonetheless consumed with a next-level hunger I had never known. It would arrive suddenly, forcefully, clouding out everything else and precluding any other physical or mental activity. I could not proceed with anything until I fed myself, ideally in a recumbent pose: a humbling condition for someone who has tended to power through, cerebrally, in denial of my somatic needs.

Though I very much looked forward to sinking into the world of another McCarthy book, my brain seemed to have evaporated; it was difficult to summon the concentration and alertness that poetry demands. The weeknights following full (yet blurry, insubstantial) days at my desk job apparently precluded this level of functioning, so I read wifthing in abbreviated bursts over the course of several weekends: a period of hoping the embryo inside me would choose to stay there, and of doing what I could to ensure such an outcome.

My fragmented state, however, was an excellent match for wifthing, a book characterized by tight poetic stitching that is at once seamless and quite obviously seamed. As in McCarthy’s previous work, this collection emerges from a wild tangle of historical source materials and personal vignette, all shattered and spliced together in a way that delivers constant surprise and delight, as well as the occasional shock and anger. Unlike some of her earlier collections that often feature vast, dense prose blocks and spacious, sprawling lineated poems, wifthing has a simpler shape: three sequences of short-lined sonnets, fitting quite compactly into a small portion of the extra-wide page that Apogee always so generously provides McCarthy’s books. This feels like a natural continuation of Quiet Book, McCarthy’s last volume, the first half of which consists of childbirth/motherhood sonnets more squarely located in the poet’s lived experience than in the archival world of wifthing. The latter is populated by witches, queens, mystics, heretics, and midwives; sometimes these categories are all collapsed. But always there is “her body as historical landscape.”

Holding McCarthy’s own experience in the role of mother—as well as the role of researcher—wifthing illuminates history with a kind of rawness, danger, and intimacy that we don’t always have the patience to see. She accomplishes this by reading deeply and broadly into the historical record, pursuing her curiosities, and using her ear and her eye to cull, magpie-like, the brightest bits of found language, then weaving them together into wondrously messy nests. In repurposing and recombining these fragments across a single sequence or a whole book, McCarthy ultimately constructs an argument out of a technique, the medium being very much the message: the past is infinitely strange, instructive, and fun to play with—and it is never over.

*

What is a “wifthing,” anyway? Aside from the obvious sense of “married-woman-as-object,” the Middle English Compendium housed at the University of Michigan Library gives us this definition:

wīf-thing n. (a) A wedding, nuptial celebration; (b) sexual intercourse with a woman.

And as the condition of being a wife was, until very recently, normatively inextricable from the condition of being a mother, McCarthy looks at wifedom and sex primarily through the lens of the childbearing obligation.

wifthing is constructed of three sequences—“margerykempething,” “qweyne wifthing,” and “goodwifthing,” each exploring a different historical place-time. Every poem in a given sequence bears the same title, e.g., “margerykempething,” and adheres to the fourteen-line sonnet form. In the very first poem, McCarthy establishes the book’s constraint, which becomes evident a few pages in. Describing her fifteenth century subject Margery Kempe as “a wifthing par excellence a female patience / figure in her fourteenth confinement,” she outlines a parallel between the structure of the sonnet form and the strictures of childbirth and childrearing. A baby’s due date is known in medical circles, somewhat horrifyingly, as the “EDC” or “estimated date of confinement”; just as Kempe gave birth fourteen times, each fourteen-line sonnet is a kind of “confinement.”

Early in the sequence, McCarthy drills home the relentless postpartum state of medieval womanhood in one sonnet’s final five lines, the last of which actually breaks the form by creating a fifteenth line:

margery kempe gives birth & gives birth & gives / birth & gives birth & gives birth & gives birth & / gives birth & gives birth & gives birth & gives birth / & gives birth & gives birth & gives birth & gives / birth

Later on in the book, we learn that the thirteenth century Queen Isabella of England “had fourteen children / all told & all survived to adulthood.” Whereas “the sonnet traditionally reflects upon a single sentiment,”[1] McCarthy’s sonnets are instead multivalent amassings of language from across time and space. Nonetheless, they are tightly constructed, each its own little reliquary, prayerbook, or piece of sheet music. Her exquisite ear for rhythm propels each sonnet swiftly forward, even as the palimpsestic texture of the source material leads the reader to linger over each fragment for deeper understanding. The poems are exhilarating to read, in part due to McCarthy’s use of caesurae of varying lengths, which punctuate her lines sonically as well as visually. “let me put it in / your ear,” she asks, and I gladly acquiesce.

*

“margerykempething” dwells in one of McCarthy’s perennial fascinations: female mystics, saints, and martyrs. Kempe was an illiterate Christian mystic who wrote (by dictation to a male scribe who may have been her eldest son—”the son made a beautiful illegible book / because everyone’s mother is incomprehensible”) a text that some consider to be the first autobiography in the English language: The Book of Margery Kempe. There is an irony in McCarthy’s evocation of this original, highly linear narrative form (autobiography) within a poetic framework that is superlatively nonlinear, that eschews narrative in lieu of fragment. But perhaps this tactic aligns with the mystical-experience-cum-schizophrenic break that is impossible to parse from the lives of those throughout history who have been “visited.”

Kempe’s chronicle begins with her first traumatic pregnancy and childbirth experience. Her life was an uncomfortable mix of enduring maternity and striving for penitence (“margery kempe gives birth in a hairshirt”), and she would eventually negotiate a celibate marriage for herself, separating from her family in order to pursue a spiritual existence. Repeatedly tried for heresy (“margery kempe is brought in for questioning / & is arrested & is arrested / & is arrested & is arrested / & is arrested & is arrested / & is arrested”) but never convicted, she appears to have experienced episodes that we might now label as postpartum psychosis but which she understood as divinely-given visions, mystical encounters with both heavenly and demonic forces.

At times giving Margery a first person speaking voice (“thirty-eight years I lived with my husband / when I was not on pilgrimages or / locked in the buttery saying prayers by rote”), McCarthy muddles the identity of her speaker(s) by incorporating thoroughly contemporary imagery (“thirty-eight years I lived with overlapped / my husband […] the daily crossword / passed between us at breakfast”). She also incorporates old vernacular language straight from the archive—for instance, Kempe’s vibrant Middle English (“kyssen my mouth myn hede / & myn fete”). And she includes tidbits, like this one, that give the reader a glimpse into the evolution of the English language itself:

the old english clyster is probably / related to clot I mean it by rote /& I speak it into your mouth a worried / language an old language an odd language / & other domestic vernaculars

“Domestic vernaculars” is a good description for McCarthy’s entire oeuvre. She also weaves a bildungsroman of her own abiding interest in etymology, starting decades ago:

the ten thousand french words the norman / conquest drove into english & then john / lost normandy in 1204 (I see / my undergraduate hand write it down)

It was in wifthing that I encountered the Middle English verb swive, meaning “copulate,” which is, in the dictionaries I consulted, first labeled as transitive—i.e., to swive someone (whereas […]wife “as a verb is rare obsolete / intransitive it is hard to wive & / thrive both in a year so they say).” McCarthy translates her poetic project, and her contemporary language, for Kempe, speaking directly to her: “the poem for the first baby is easy / for the first time you fuck someone (margery / kempe that means swive) but what about the hundredth / the hundred-hundredth time” […] And later: “you are the shape of my midlife crisis / margery kempe […].”

McCarthy’s evocation of coital monotony, a kind of relentless repetition that yields, via childbirth and childrearing, subsequent monotonies, contrasts with her deployment of repetition as a technique in that the latter is never boring. On the contrary, her inventive turning over and over of language is always breathtaking in its novelty, skilled as she is at creating novel contexts for phrases and images to reappear, exhibiting the kind of creativity within restraint that is a hallmark of masterful poetry. In writing this review and doing keyword searches in my PDF galley to locate specific passages, I was invariably rewarded by seeing how many instances of a given word would crop up—revealing new ways to read the book, newly deepened and tighter-woven webs of association and repurposing of phrases and lines within and across its three sequences.

One of the particularities and pleasures of wifthing is the way in which these three sequences, clearly set apart from one another by their poems’ titles, at the same time bleed into one another: there are no section titles, no page dividers, nothing to keep time and space from slipping suddenly into another frame. So it is that “margerykempething” ends forcefully (“a splinter & a cluster are both red / & I mean them with my whole vulgar tongue“—“vulgar” referring to both the vernacular of Middle English and to the coarse sexual language of swiving and fucking), and the book barrels ahead without pause or transition into the next sequence, “qweyne wifthing.”

*

Now we are in the realm of realms, where a high-born woman is not powerful per se but only insofar as her body can broker, through marriage and heir-generation, political deals and property transactions. As “a living talking walking wifing / fucking birthing breathing speaking treaty,” a royal woman “makes her body by making other bodies.”

In this section we are introduced to Margaret of Anjou, Queen of England, whose life began just before Margery Kempe’s ended, in the early-to-mid fifteenth century. In Margaret’s case, because her husband, King Henry VI, struggled with severe episodic mental illness, she did assume de facto control of the English throne. Yet her agency was rooted in her relationships: a daughter of French nobility, Margaret was married off to Henry as part of a truce in the Hundred Years’ War; hence McCarthy’s continual reference to “her treaty body.”

“qweyne wifthing” follows multiple royals and noblewomen of the Tudor period, and still another Margery/Margaret enters the text—this time Margaret of Beaufort, married at twelve to twenty-four-year-old Edmund Tudor and primiparous (giving birth for the first time) to the baby boy that would become King Henry VII, the first monarch of the House of Tudor (“she will / give birth scared & small & thirteen to the future”). Mystical visions are also part of Margaret Beaufort’s story, as she later claimed she’d had a vision, at age nine, that told her to formally consent to the marriage. She, too, would later take a vow of chastity, while still married to her fourth husband.

[…] one effective way to / justify fucking a twelve year old girl / is to have a vision for her to have / a vision / that gives you her body her / money her land her long family even / if she predeceases you if she has a child / by right of courtesy of england everything / hers is yours […]

As Queen Margaret of Anjou pronounces in one poem, “I transfigure my body / the matrix of future kings.” All the women we follow in this sequence have in common their status as such “matrices,” carriers for the royal issue: useful and used, adored and abused. Hence, “her body goes all soft & / medieval all lapis lazuli matrix.”

This language immediately called to mind, for me, my childhood rock collection, which featured something my specimen ID guide called a “garnet in matrix”: a tiny, dull red gem (my birthstone) embedded in an even duller piece of blackish stone. Apropos of McCarthy’s etymological bent, “matrix” turns out to be a rich word, derived from the Old French for “uterus” or “pregnant animal” and ultimately, of course, from the Latin mater, for “mother.”[2] [3] I can imagine the delight with which McCarthy must have devoured background like this:

The many figurative and technical senses [of “matrix”] are from the notion of “that which encloses or gives origin to” something. The general sense of “place or medium where something is developed” is recorded by 1550s; meaning “mould in which something is cast or shaped” is by 1620s; sense of “embedding or enclosing mass’” is by 1640s.[4]

Here is the female body in the public record, AS a public record—a repository of political maneuverings, a vehicle for—a matrix for—all the moves of history):

the great grand multiparous is too leaky / efficient & experienced uterus / a question about its echotexture / its living ligatures that prevent / hemorrhage & elizabeth of york / another matrix brought to bed on / candlemas gives birth to & dies from her / eighth childbirth eleventh february

Speaking of Elizabeth of York (or is it Elizabeth Woodville? Does it even matter? [“she is always / the same woman but those are different / women”]), McCarthy notes that “elizabeth’s great grand multiparous / body is the most public of languages.” It seems fair to say that wifthing is itself a “great grand multiparous” (meaning, in medical terminology, having given birth seven or more times) book, a fruitful generator of speech and image.

*

The book’s third and final sequence, “goodwifthing,” establishes in the first sonnet a more contemporary frame that, even so, continues to collapse into the historical (“my invisible scrutinized midlife / goodwyf body minivan & tankini“). The poet qua poet enters more forcefully now, to synthesize the foregoing material and situate herself more plainly within the text. At the same time, “goodwifthing” takes as its primary concern the legal and bodily precarity of the historical midwife/healer figure and the punishments leveled against her:

this is labor too goodwyf but nothing / waits at the end of it the goodwyf body / is at its most crone when its edges touch / monster & mother & reproduction / but it makes nothing & that’s when it burns

We surmise that a “goodwife” is “an archaic or dialect wife an old / or uneducated woman.” More simply, it was a polite term of address for a woman or perhaps, more specifically, a female head-of-household. It is this latter meaning that obtains more clearly in “goodwifthing,” as McCarthy continues to turn over the various meanings of the wife/mother figure in the present day. “Goodwife,” or “goody,” also carries for the contemporary reader shades of association with “midwife,” not only for the word’s linguistic shape but also for its relationship, in the popular American imagination (via Arthur Miller and Nathaniel Hawthorne), to Puritan New England and the witches of Salem. Midwives and healers might have made up around 25% of the accused,[5] a pattern already established during the centuries of witchcraft hysteria back in Europe. In turning to the Salem trials, then, McCarthy illuminates that connection between the goodwife, the midwife, and the heretic. (In a 2020 tweet responding to the prompt “What would you be dead from by now if you lived in medieval times?” McCarthy answered, “An afterbirth hemorrhage at age 36—I would have needed a witch.”)

The book’s taut shape paunches out a bit in the third section, as several poems break with the sonnet form that McCarthy has established—their fourteen lines nonetheless lengthening, the ragged right edge becoming justified, etc. And perhaps that is entirely appropriate: the pregnant body grows large and strange at the end, stretching to hold the argument of a new human life. Too, the straight facts require a different structure; these pieces are, for the most part, delivering cold, hard information (timelines, trial transcripts) with less editorializing than the rest of the book.

Throughout this sequence, McCarthy directly addresses Mercy Lewis, one of Salem’s most vocal accusers (“mercy you’re a metaphor for everything / & always were you never stood a chance“). Having lost her parents and many members of her extended family to a violent episode of Wabanaki indigenous nation self-defensive resistance just a few years prior to the trials, Lewis would appear to exemplify the adage “hurt people hurt people.” McCarthy seems interested in that cycle, which applies to many of the teenage girls embroiled in the hysteria—orphans, refugees from frontier violence, survivors of abuse themselves: “I guess I believe the salem afflicted / were faking & suffering both that both / can be true.”

As a woman living under patriarchal capitalism, you’re damned if you do and you’re damned if you don’t: though “it’s better to marry than to burn […] we marry & burn” anyway. A few poems throughout the collection center this “we,” turning the classically singular sonnet voice into a litany: “we draw winterward we rhyme with daughter / we in lieu we sound we rave vernacular […] we escape the fire we lucky creatures / we latin we goodwives we daughterthings / we patience figures.” Thus the individual narrative is transmuted into a multiform reflection of the blending and genericizing of female experience that characterizes history:

each goodwyf is plural anonymous / unlikely to speak but with a trusted / introduction a trusted interlocutor / who is speaking in the middle of this / sequence […]

Here it seems that McCarthy is positing the role of the poet as medium for conveying the speech of goodwives from across the centuries, as she so skillfully does. She shows the raggedness of archival materials, stitching one narrative edge to another, quilt-like, and beginning a new story (albeit a still-fragmented one). And where the warp and weft are threadbare, the light of today shines through the text: “the long suburban hymns of winter I / get off the train & the whole neighborhood / smells of woodfires & laundry detergent / our common body she makes her body / making other bodies […].”

The book is also threaded with what seems to be the poet’s meta-commentary on the fallibility of her own procedural work with the historical record’s scant and opaque vestiges of motherhood (“this sentence is from several failed attempts […] & the process has already failed“). Directly addressing the reader for what feels like the first time, McCarthy declares in “goodwifthing”: “I’m middle-aged I’m sentimental I’m / never more confessional than when I /write about salem & share facts with you […].”

And it’s true: whereas her previous books have featured many more of her own family’s intimate domestic details, the most personal McCarthy gets in wifthing is the disclosure of her own research process. As I can attest to from my own research-based writing process, it is vulnerable—and perhaps impossible—to convey the experience of one’s deeply intimate encounter with an archive. For McCarthy, this encounter extends back decades. Addressing Mercy Lewis, she says: “when I revisit you I visit / my first childhood historical love.” And in the notes to the book, she cites “my sentimental source, my undergrad copy” of The Book of Margery Kempe.

The researcher is a person with their own life history, their own fragility. Toward the end of the book, McCarthy gets more meta about her own research process:

mercy leaves no architecture & no / archeological evidence here / I finally went to salem & feel / complicated archive of all floods […] perhaps it’s time to read something else now

This “archive of all floods” is also a literal geologic stratification. In “goodwifthing,” the image of the midden—an archeological site consisting of a dumping ground for domestic refuse such as bones, shells, broken tools and vessels, and other household goods—comes into relief. A midden is kind of a matrix: a geologic medium that can provide archaeologists with important information about the time and place in which these domestic items accrued. Evoking the New England coast where the Puritans made land (“a tidal shell scatter an archive of between“), McCarthy asserts that wifthing is itself a midden, “a large accumulation of small / things chalky softwhite left on my fingers […].”

But as much excavation of the historical literature as McCarthy can do, there will always be an unresolvedness, an uncrossable distance between the contemporary researcher-writer and their historical subject(s): “the main function of the goodwifthing is / what […] & by definition one cannot get / any closer to the offing one can / not get any closer to that past body.” Still, what I have learned from McCarthy’s work is that intimacy is an action. We get out of history what we put into it: proximity, belief, respect, wonder, doubt.

*

At the same time I was slowly reading wifthing, I had coincidentally picked up Sarah Knott’s Mother is a Verb: An Unconventional History (FSG, 2019). As Knott, a historian and researcher at the Kinsey Institute, explains, “Mother is a Verb is a history of childbearing in Britain and North American [sic] since the seventeenth century: based on anecdote—what can be drawn out from the shards and fragments of the archives—and composed in the form of a first-person essay.”[6] (Knott, too, illuminates the verb swive.)

In my more exhausted first trimester moments, I read Knott’s prose and felt accompanied; I also felt that Knott and McCarthy should know one another. In her chapter titled “Time, Interrupted,” Knott notes how “the thousand little nothings” of maternal activity “[fragment] time”: “Being interrupted is the workaday experience of anyone who is mostly beholden, at some kind of first hand, to someone else, time not being their own.” This was not only my experience of consuming wifthing as a putative mother-to-be, but also what I perceived as the underpinning quality—the ethos, even—of McCarthy’s project: “The halting, the interruption, constitutes the everyday. I am mid-thought, mid-sentence, mid-task, and then I am stopped.” The specter of this kind of existence was one major reason I for so long resisted the role of mother and only started trying to conceive at age 35, when any potential pregnancy would already be cast as “geriatric.” (When filling out some medical forms the other day, I noticed that my practitioner had labeled me as an “elderly primigravida,” which simply means a woman older than 35 who is pregnant for the first time—and which also rings like a phrase straight out of wifthing, or another of McCarthy’s books.)

Interruption yields micronarrative, otherwise known as anecdote. In a section of Mother is a Verb that describes her methodology, Knott cites psychosocial theorist Lisa Baraitser:

‘Motherhood lends itself to anecdote,’ Baraitser explains, because of the ‘constant attack on narrative that the child performs.’ A small child continually breaks into maternal speech. The mother’s personal narrative is ‘punctured at the level of constant interruptions to thinking, reflecting, sleeping, moving, and completing tasks.’ Thus rejecting narrative as a useful starting point, Baraitser turns to anecdote as the basis of interpretation. She casts the state of being interrupted as mothering’s key condition.

As Knott points out, the fragmentary nature of motherhood means that its historical traces are also extremely fragmentary: the letters of middle- and upper-class mothers of small children often end abruptly, with or without an explanation that the baby needs attending, resulting in “Broken-off letters, short letters, impoverished letters, unwritten letters…” Of course, working-class mothers rarely had the luxury of, or literacy for, recording their experiences.

In defense of the unusual form of her book, Knott posits: “Let’s think of anecdote as neither bare or incomplete, but exactly what is needed. A historical interpretation can reside in the slow accumulation of a trellis of detail. Juxtaposing, contrasting, pausing over, and serializing anecdote can make for a full historical interpretation by comparison and accretion.” I think McCarthy would agree. This type of mental fragmentation is aligned with the form of wifthing, composed as it is of textual fragments that repeat themselves, repetition being another condition of maternity. In embracing the fragmentary nature of both the historical record and of motherhood, McCarthy has developed a singular voice, even as that voice is constituted from—at this point in her career—hundreds of other voices. In the notes section of wifthing, we learn that McCarthy incorporated (as is typical for her process) far-ranging materials from academic papers, primary sources like court depositions and accusations from the Salem trials, literature, news media, personal conversations, dictionaries. The found texts also include lines from more than a dozen other poets, from CAConrad to Geoffrey Chaucer. Yet McCarthy’s voice is recognizably her own, even as it is multiparous. The arts of curation and juxtaposition are where her hand is seen.

*

The second trimester of my pregnancy started on the winter solstice, which was also, coincidentally, the Great Conjunction: the orbital alignment of Jupiter and Saturn, an astronomical event that happens approximately every twenty years but that had not been so acute in nearly four hundred—just about the time that Salem was first settled by the English.

On that day, I had an extra-powerful ultrasound that screened for possible signs of chromosomal abnormalities or birth defects (all good on those fronts) and, miraculously, let me observe the hemispheres of my two-inch-long fetus’ brain. Grateful to be leaving behind the exhaustion and high risk of the first trimester, I departed the appointment and returned to writing this review—immensely grateful, as well, for the many privileges that make it so that I have not borne babies against my will and am unlikely to die in childbirth.

The juxtaposition of the unfathomably enormous Great Conjunction and the difficult-to-grasp fetal imaging was a trippy one, evoking for me these wifthing lines: “an old language an odd language / our common body its echotexture […].” This last word refers to, as McCarthy tells us in her notes, a radiologist’s comment during one of her transvaginal ultrasounds. In this context, the word seems to speak of Middle English and its reverberations over time. As Sarah Knott puts it, “…the mother [can] always be interrupted. She inhabit[s] unending broken time.” Perhaps this kind of maternal akashic field is what has nurtured McCarthy’s oeuvre: the place where her poems all still live and from which they continue to spring and to find form.

As McCarthy proclaims, “we treat history like a bad mirror“—perhaps squinting to see ourselves in its cloudy surface, or trying to clean or polish it for greater clarity, to suit our curiosity and our vanity—favoring our own time and pitying, by comparison, all others past. She also doesn’t shy away from articulating the specific horrors of contemporary parenthood, e.g., school shootings and “permanent lockdown[s].”

But I already feel more accompanied in the difficulties of motherhood because of her explications, however dark they tend to be. McCarthy is a highly prolific poet who also has three children, and writes about them movingly—a fact that gives me hope, as one of my deepest fears of motherhood has always been the permanent annihilation of my writer-brain. I am perhaps not an “inevitable / wifthing,” or perhaps I am; “like all mothers she both over- & under- / estimates her own importance & or / influence.” So be it—as it has been for others before me, and as it will be for those to come.

[1] https://www.poetryfoundation.org/learn/glossary-terms/sonnet

[2] https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/matrix

[3] https://www.etymonline.com/word/matrix

[4] Ibid.

[5] https://imss.org/2019/12/18/a-note-from-the-collections-midwives-and-healers-in-the-european-witch-trials/

[6] https://history.indiana.edu/faculty_staff/faculty/knott_sarah.html

*

These five poems are from my book Comfort, forthcoming from Spuyten Duyvil this year. Comfort was deeply influenced by Pattie’s poetics, particularly with regard to its found text collage methodology and its collapsing of multiple female subjectivities into a singular sort of litany. The form of these prose blocks is directly indebted to her book Marybones (Apogee, 2012).

*

*

Sarah Heady is a poet and essayist interested in place, history, and the built environment. She is the author of Comfort (Spuyten Duyvil, forthcoming 2021) and Niagara Transnational (Fourteen Hills, 2013) and the librettist of Halcyon, a new opera about the death and life of a women’s college. Her latest chapbook, Corduroy Road, was released by dancing girl press this spring. Raised in New York’s Hudson River Valley, she now lives in San Francisco, where she is a co-editor of Drop Leaf Press, a small women-run poetry collective. She is currently reading Mindful Birthing by Nancy Bardacke, Birthing From Within by Pam England and Rob Horowitz, and Bright Felon by Kazim Ali.