The Compendium and Dream Books: A Short Essay About Lists and Books of Lists, That Itself Contains a Number of Lists

Geoffrey Nutter

September 10, 2021

Elecment Series #11

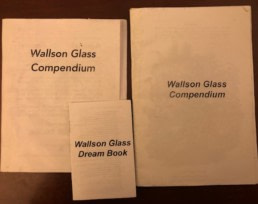

The Wallson Glass Compendium is a pamphlet I give to poets who participate in the Wallson Glass Poem-Making Sessions, a series of salons or “events” that I’ve been running in New York City since about 2013, first out of my apartment in the Inwood neighborhood on the Northern tip of Manhattan, then via Zoom beginning the first week of the pandemic lockdown in March 2020.

The Compendium is a book of lists, and a book of lists of lists, which is constantly expanding—it currently contains over 300 of them. Here are a few examples of the lists (the numbers indicating each one’s place in the booklet):

38. Manhattan restaurants from the 1970’s

46. Titles of science fiction films from the 70’s

51. Names of Comic book drugs

52. Types of waterfalls

54. African Market Literature

84. Calls to action in North Korean propaganda slogans released in 2015

91. Types of Industrial buildings and structures

93. Discontinued candy and gum brands

94. Some books in DaVinci’s possession when he left Milan

106. Some principle members of the Aztec pantheon

128. Opening salutations from the Paston Letters

183. Proverbs from Ray’s 17th century A Handbook of Proverbs

197. Toho films that feature Kaiju

209. English names of water features on the moon

214. English titles of Italian giallo films

234. All lines containing the word “purple” from the Concordance to the Poems of Emily Dickinson

247. Words Marianne Moore only used once in her collected works

But there is a requirement for the lists that go into the Compendium: they should have no practical or educative value. It isn’t a world record book or a list of curious facts like The Book of Lists or a useful guide like the Pocket Ref: both of which I love. It is more along the lines of the books of curiosities that were popular in the 19th century, books such as The Homebook of Wonders in Nature, Science, and Art, or Ebenezer Cobham Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. It also is in the spirit of the wunderkammer of the 17th century, in which collectors (Sir Thomas Browne, author of Urne Burial and Letter to a Friend, is an example) crowded objects together in “cabinets of wonders.” The diarist John Evelyn—contemporary of his more famous counterpart Samuel Pepys—records seeing many such cabinets, among a host of fantastical marvels of architecture and technological ingenuity, in his travels around Europe. Don Saltero’s famed coffee house in early 18th century London contained a number of glass-encased cabinets of curiosity, the contents of which are recorded in a little pamphlet called A Catalogue of the Rarities to be Seen at Don Saltero’s Coffee House in Chelsea, and include (just to name a few):

[All texts are reproduced as they appear in the pamphlet]

An horizontal sun-dial.

A Queen Anne’s farthing on a tobacco stopper.

One hundred and four silver spoons contained in a cherry stone.

A foetus of a land armadilla.

An almanack for a blind man.

A Chinese seal.

A bowl and nine pins in a box, the bigness of a pea.

A piece of a glass bottle, encrusted with white coral.

A petrified peach.

A black scorpion, very large.

Two birds of paradise.

A petrified pear.

A curious sprig of white coral.

These lists were picked from a number of different sources. I found many of them in my wanderings in the Rose Reading Room at the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street in midtown Manhattan. In the Reading Room, one can find old books on shipwrecks in the age of steamships; a dictionary that defines the rich argot of the underworld up to the early 20th century; a book with lists of all proper names Edgar Allan Poe used in his fiction; a catalog of the last lines of thousands of English poems; a tome that contain synopses of every science fiction story that ever appeared in pulp magazines under the editorship of the great 1920s and 1930s curator of speculative fiction Hugo Gernsback. And on and on. Another source was the fantastic “library” of Google Books, which contains millions of books scanned from the collections of public and university libraries around the country, from the 16th century on, all accessible for free. Almost all sources of the lists in the Compendium are a result of wandering.

I have a compulsive love for lists. I also love strange little books and pamphlets, like the kind you might find on a subway seat or stuck between books at the Strand or on a wire rack in a botanica. One of the most beautifully weird genres of strange little books is the dream book. I discovered dream books for the first time in the early ‘90s at a bodega on 125th Street in Harlem. The one I picked up and leafed through and bought was a pulpy little booklet called The Lucky Star Dream Book by one “Professor Konje,” and it contained mysterious and vaguely sinister-looking lists of numbers, many in bold-faced 48-point font, crowded together in columns on its pages. The first and last several pages contained ads for other dream books (the Policy Joe, Grandma’s, Success Dream Book), brief exhortations about living a successful life, and calls to action for those who would like to sell dream books:

“AGENTS wanted to distribute the greatly revised Success Dream Book. This book now contains twice as many dreams as the former edition!”

*

But the bulk of the book’s content consisted of lists of words with three-number combinations next to each one. These books, I soon learned, gained popularity in the 19th century in American cities such as Chicago, Detroit, and New York and were used to pick numbers for illegal lotteries—games such as “the daily number” and “policy.” As a bonus, each image “unlocks the secrets of your future.” If you dream of a large building, you find the entry for “building” in the dream book. If it’s built of stone, this denotes riches. A small wooden building denotes “ordinary circumstances.” To dream of a hairy monster denotes excessive pleasure. A brand new hat: increase of knowledge. A hamburger steak: reunion. You will also find meanings for such dream images as mermaids, Quaker Oats, pugilists, sewing machines and shipwrecks, tusks, watermelons, wharf rats, yarn, yams, and yule logs. I’ve found similar pamphlets in moldering stacks of books for sale on the street in Santo Domingo, where I go occasionally to visit family: some had no real text at all save for a single word in Spanish and a number combination below a picture of an object or group of objects—say, a head of lettuce, a hole punch, and a sturgeon (an actual combination from El Significado de los Sueños).

You can still find many discussion boards online where people from all over the United States, the Bahamas, and the Dominican Republic discuss how to pick winning three-number combinations. The participants in these discussions use a specialized vocabulary to discuss gambling secrets and ways of beating the odds, and their almost occult tone is vaguely unsettling in nature.

As a beginning teacher of poetry “workshops” I noticed something that I thought was a pretty great discovery at the time, but will not be news to anyone who has read or participated in poetry critique: when a group discussed a poem, there was always consensus on the best lines, and that consensus was almost always because of one simple fact: the best line or lines always contained an image. This would be even truer for poems that were otherwise problematic in terms of clarity. In a poem trying to explore an idea or deduce a truth or tell a story, the thing that resonated with readers most powerfully was the Image, in its baffling specificity and its power to make and disclose meaning on its own terms. In order to try to help poets get images into their poems, I began asking them to compile lists of nouns that they could draw from: a kind of toolbox. When I asked the poets to read their lists back aloud, everyone in the class agreed there was a kind of associative poetry to them. Interesting accidents that made meaning, intuitional chains of associations—words struck up against each other, stood beside one another in a way that was both meaningless and super-saturated with indefinable possibility.

Eventually, to save time and augment their list-making, I started distributing to each student a single page with about 20 lists on it: kinds of birds; rocks and minerals; butterflies and moths; kinds of bridges; ancient cities; others with different kinds of glue, ships, clocks, and “random things” and “some places” (junkyard, orchard, train station, prison, etc.). Originally, there were a couple reasons for this: first, it saved time. Second, poets need to know the names of things—they give us great pleasure, not to mention the ability to say more and to expand our possibilities of meaning-making. One might not know that there is such a thing as bone glue, or butterflies called purple hair-streak and cloudless sulphur. Or that there was a 19th century parlor game called “the tormenting bee.” Or be aware of the existence of the shell called the flame auger or an herb called prickly asparagus.

When I ran off copies of this sheet of lists and gave it to some poets at Wallson Glass, they seemed to like it. So I expanded it and turned it into a pamphlet with maybe 50 lists. Then I added to it.

You might suspect that grabbing words and phrases from lists is somehow cheating, or a way of composing that is overly artificial. But since at least the 17th century, haiku poets of Japan have used saijiki, a kind of haiku dictionary that lists kigo: words and phrases that evoke particular seasons. Kigo were traditionally required in haiku. If Bashō or Onitsura or Buson got while writing a poem stuck—out came the saijiki. There one could find “meteor flies,” “equinoctial storm,” “autumn waves” and “noctilucence,” “Floating Lantern,” “Star Festival,” “departing and remaining swallows”; “the first mushroom” and “fish-scale clouds.” I recently asked the great haiku translator Hiroaki Sato about saijiki—according to him, they are still regularly published in Japan. He has the largest recently-published saijiki, containing fifteen to twenty thousand season words. A Japanese bookstore sells this multivolume marvel.

“Artifice” is a word I don’t hear much in connection with art these days. But the connection used to be clear: art involved artifice. I think part of the reason the haiku poets felt comfortable with the saijiki was their understanding that the truth in a poem is a matter of imagistic and connotative precision and aesthetic symmetry, and when these things come together the poem will be truer than simply a mimesis of the triggering subject in its details (i.e., the thing/object/event/scene, etc. in the objective world of phenomena which the poem purports to be about). Basho felt perfectly comfortable changing the setting of a haiku from forest to ocean in his edits, for example, if it made the poem work better. Artifice, then, is the thing that gets a poem to precision and truth. It is, among other things, the process of visualizing and then seeing clearly and looking at a version of the objective world in the imagination.

In the humongous 18th century Chinese novel Story of the Stone, Cao Xueqin’s characters engage in numerous poetry gatherings and contests, in which they are required to compose poems with almost ludicrously elaborate sets of constraints, rules, allusions, references, metrical patterns, and images. Ditto the haika no renga gatherings of Japan, where verses were passed from poet to poet, each successive verse having to adhere to guidelines that would guarantee intuitional sequences of action and image—the subject, scene, and season, for example, had to change from poet to poet for each new verse. This resulted in poems that we’d recognize today as being a kind of associative surrealism.

And such artifice is not unknown in the history of visual art, as well. Staffage is a familiar element of European painting: small human figures that populate the foregrounds of landscapes, the little people you see strolling in a Venetian plaza or crowded Dutch seaport, or in a French garden dreamscape among ivy-covered ruins, or a Flemish biblical or hunting scene. In the 19th century there were pattern books with ready-made cut-and-paste staffage figures—a visual analog to the seijiki. I’m reminded of the writer/painter Henry Darger, who made long scroll painting to illustrate The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion, his immense novel that detailed, over the course of more than 15,000 pages, the epic battles between civil war soldiers and a race of little girls endowed, inexplicably, with penises and rams’ horns. Darger had an amazing sense of scale and composition, and was able to create panoramas made up of grotesquely big and over-verdant flowers and vast cloud-scapes populated by a staffage of hermaphroditic children suffering terrible acts of violence and, on occasion, benevolent dragons (or blengins) with rainbow-striped wings. But since Darger was unsure of his ability to draw the human figure, he would search for images of little girls in magazines and advertisements and then take them to the local pharmacy to have them reproduced, reduced or magnified in size. He was then able to cut and paste the figures—as found in the original source (in frilly blue dresses, etc.); or altered (stripped of clothing, etc.)—into his otherworldly landscapes.

But aside from aiding the compositional process, lists act as a kind of simple-minded reminder—if a reminder is even necessary, and maybe this is partly why we need poetry—that the world is strange and big and various. Poets have always wanted to bring as much of the world into their poems as possible. It’s why Homer smuggled a shield with everything in the universe engraved on it into a poem whose action takes place solely on a blood-soaked stretch of beach: he wanted to show alternatives, a world of possibility and beauty beyond a limited, stunted world of violence and death. And it’s why Dante compares the sight of souls being cooked and basted in infernal tar to a shipyard in Venice and all of its busy activity in a poem that otherwise takes place in the busy inactivity of Hell. Emily Dickinson’s imagination reached out into the world and found a place for seemingly everything in her poems. And one of the most famous examples of a poetic omnium gatherum is Christopher Smart’s long poem composed during his incarceration in a mental institution: Jubilate Agno is a long, sprawling list poem, a litany that catalogs the names of hundreds of gems, plants, flowers, animals, sea creatures, saints, real people, and Biblical figures. Smart is supposed to have drawn words from the books in his possession—an herbal, a book on gems, the Bible, Pliny’s Natural History—and names of people from contemporary obituaries.

A thing I like about poetry is its power to surprise, delight, and transport by combining images and words in ways that are resonant, suggestive, precise in texture and connotation, and that incandesce. There is something to lists themselves that is pure poetry. The magic of the list lies in juxtaposition, in the proximity of each element to what comes before and after. A barracuda is interesting. But when it comes after “honeydew” and before “bonfire” it becomes something else entirely: it carries the possibility of meaning, a suggestion of significance that is, unlike metaphor, completely open and free of the burden of meaning. This is the kind of openness that the Surrealists and the channelers of magic like Maria Sabina knew well. When you listen to someone reading such a list, inexplicable areas of creative possibility begin to light up in strange and interesting ways. Obfuscating language—language that has the appearance of meaning and purports to have meaning—is used to mislead and baffle in some spheres of life: in the formulations of propagandists or in the endless qualifications and shaggy dog stories of the narcissist or the pathological liar. But the very meaninglessness of the list—and indeed of poetry—is what gives it a kind of sharp, cold purity; it quickens the workings of the mind and activates the imagination. C.S. Lewis once described laughter as “a meaningless acceleration in the rhythm of celestial experience.” There is an apt comparison here: perhaps the thing that poetry can do uniquely well—contrary to any prescriptive purpose we might sometimes be tempted to press it into—is evoke and activate this ultimately useless delight and sense of strangeness. Here, then, is poetry’s power (though not its only power): “acceleration,” and even if not in a heavenly sense, an acceleration nonetheless: a quickening and brightening in the intellect and in the sensation of being alive.

A couple things about the Compendium as physical object: it has to be small. A book should be able to be hidden. As a museum guard in the 90s, I came to understand the importance of being able to appear to be working while actually sleeping, dreaming, or reading (or a combination of all three), a skill I endeavored to perfect during several years working at a poet’s sinecure in the tech department at a large media company in Times Square that shall remain nameless. You should be able to read a book when you’re supposed to be doing something more productive. Also, while I’ve sent electronic versions of the Compendium to a few people over the course of the pandemic, it works most effectively as a physical object. Its contents should not be searchable in any manner (there is no table of contents), save for stumbling through the pages—a way of discovering things that becomes increasingly rare in an age when we know exactly what we are looking for and can find it immediately with a search term (though I am a fan of Wikipedia—especially the “random article” function). Poets need to be able to stumble upon words and books: be it walking through a library and distractedly opening a book whose borrowing slip, you discover, indicates it has not been checked out since 1957; or looking for a word in the Oxford English Dictionary and your eye straying to the word pragnänz or prolepsis.

Following the spirit of the old dream books, dittoed off in some basement in Newark or Poughkeepsie, the Compendium is and should be a slap-dash, stapled together affair, rough and ready, printed in a standard-issue Helvetica font on Hammermill copy paper and run off on an English department copy machine, then bound in a single signature with a saddle stapler.

A result of my own love for such oddities as the wunderkammern, dream books, and saijiki, the Compendium is ultimately meant to be a practical tool for poets. And hopefully, like poetry itself, a source of pleasure.

Geoffrey Nutter is the author of A Summer Evening (winner of the 2001 Colorado Prize), Water’s Leaves & Other Poems (Winner of the 2004 Verse Press Prize), Christopher Sunset (winner of the 2011 Sheila Motton Book Award), The Rose of January (Wave Books, 2013), Cities at Dawn (Wave Books, 2016), and most recently, Giant Moth Perishes (Wave Books, 2021). In 2019, he traveled in China, giving lectures, workshops, and readings as a participant in the Sun Yat-sen University Writers’ Residency. Geoffrey’s poems have been translated into Spanish, French, and Mandarin. Soir d’été, a bilingual edition of his poems translated into French by poets Molly Lou Freeman and Julien Marcland, was recently published in France, and a German translation of his book Water’s Leaves & Other Poems will appear in 2021. He has taught poetry at Princeton, Columbia, University of Iowa, NYU, the New School, and 92nd Street Y. A bilingual Italian/English collection of his poems is slated for publication in 2022, published by Nino Aragno Editore in Turin, Italy. His book Water’s Leaves & Other Poems will appear in German/English translation through Austrian PEN Centre in Vienna in 2021. He currently teaches Greek and Latin Classics at Queens College. He runs the Wallson Glass Poetry Seminars in New York City.